If inflation rate has been outside RBI’s comfort zone for the past 12 months and RBI has also bumped up inflation forecast, then why hasn’t it raised repo rates?

Dear Readers,

Exactly a year ago, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman was asked if India was facing stagflation, which refers to a phase when an economy witnesses ‘stag’nant growth and persistently high in’flation’.

The question was asked because India’s growth rate in the first two quarters of the last financial year (2019-20) had decelerated sharply to a six-year low and retail inflation — or the rate of increase in prices that we face as consumers — had shot up in November 2019.

She had reportedly replied: “I have heard of the narrative going on and I have no comments to make”. To be fair, at the time, calls of stagflation were quite premature.

For one, retail inflation had gone up for just a couple of months. Moreover, the main culprits were food prices, especially fruits and vegetable prices, which had shot up after unseasonal rains curtailed supplies.

It was hoped that before long, the “transient” spike in inflation will subside and the GDP growth will resume momentum.

But neither happened.

GDP growth continued to falter — it kept getting slower in the third and fourth quarter before Covid forced it to contract by 24% and 7.5%, respectively, in the first two quarters of the current financial year (2020-21).

The rate of Inflation remained persistently high until Covid disruption made it worse.

? Follow Express Explained on Telegram

This brings us to the worries of India’s central bank — the Reserve Bank of India — which released its latest bi-monthly review of monetary policy last week.

The RBI is, by law, required to maintain the retail inflation rate within a band of 2% and 6%. At the start of the Covid breakout in late March and again in end-May, the RBI furiously cut interest rates so as to boost economic activity, while largely ignoring the hardening retail inflation rate. Governor Shaktikanta Das made it amply clear that the RBI will do everything in its power to revive growth.

But in the last three policy reviews, including the latest one, the Monetary Policy Committee of the RBI has decided to keep the benchmark policy interest rate — the repo rate or the interest rate at which it lends money to banks — unchanged.

For those who track monetary policy closely, this decision was a foregone conclusion even before the RBI announced it.

Why?

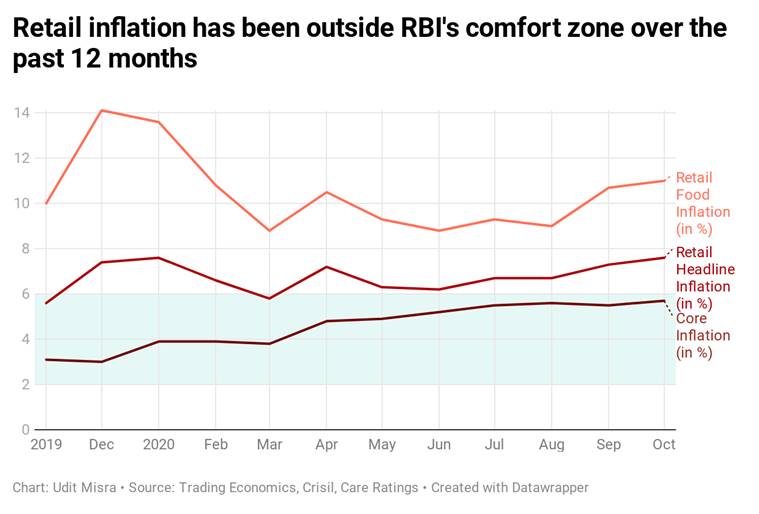

Because even though India’s economy is struggling to grow, the retail inflation rate — calculated using Consumer Price Index — had remained above RBI comfort zone for almost every month since last November (see Chart 1).

Before the December 4 policy announcement, most people believed — much like in November and December last year — that it is just a matter of time that retail inflation will come down, and when it does, the RBI will restart cutting interest rates to boost economic activity.

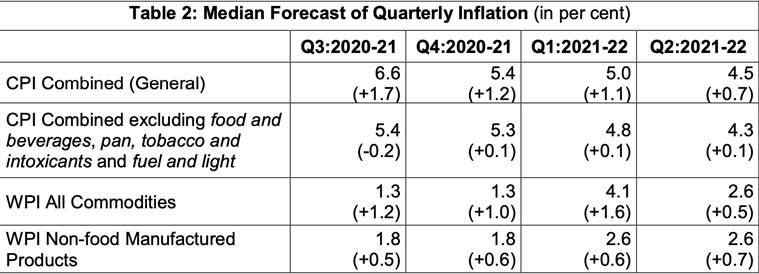

But here lies the most important takeaway from the latest monetary policy review: At long last, the RBI admits that, far from easing up, the inflation outlook is getting worse. “The outlook for inflation has turned adverse relative to expectations in the last two months,” stated the policy statement. As a result, the RBI has substantially raised its inflation forecast not just for the current quarter (October to December) but also for the two quarters after this one — January to March and April to June in 2021.

Look at Table 2. It is taken from RBI’s latest “survey of professional forecasters on macroeconomic indicators”. The figures in parenthesis show the extent of revisions. As can be seen by a sea of plus signs, forecasters have bumped up inflation forecasts across the board — be it retail or wholesale, headline or core, this quarter or two quarters hence.

Also in Explained: Gold prices now down, but does it make sense to stay invested?

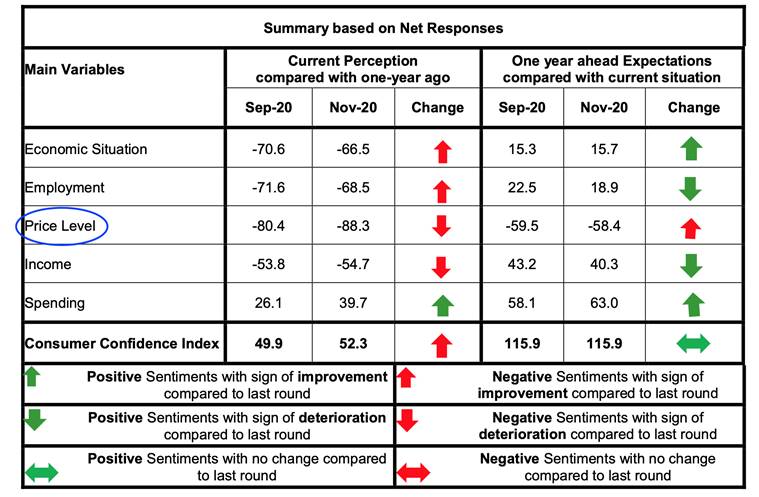

Table 3, which is taken from RBI latest “Consumer Confidence Survey”, is quite revealing too as it shows that, in the year ahead, consumers are optimistic about every macroeconomic variable barring the issue of prices.

The upshot of RBI’s assessment of the economy was that while growth is recovering, it is not as broad-based, and inflation is rising and it is becoming more broad-based.

The question some of you may justifiably ask is: Why hasn’t the RBI raised interest rates? Isn’t it bound by law to maintain price stability?

This is a valid query. After all, if one looks at Chart 1, it is clear that over the past 12 months not only has the headline inflation rate been outside RBI’s comfort zone but also food inflation has routinely touched double digits. Worst of all, even the core inflation rate — or the inflation rate after excluding food and fuel prices (both of which fluctuate quite a lot) — has continued to climb all through the year and is now threatening to breach the levels set for headline inflation.

A big part of the answer to this question lies in understanding the reason why inflation is high in India and whether raising repo rates is the solution to that. As the RBI notes, the ongoing inflation spiral is being fuelled by supply chain disruptions, excessive margins and indirect taxes.

For instance, if the fuel prices are higher because the government keeps raising indirect taxes on them, then how far will a repo rate increase bring down fuel prices?

Don’t miss from Explained: Why RBI has asked HDFC Bank to stop digital launches, new credit card sourcing

Similarly, if the price of a good is higher today because the supply of goods is disrupted thanks to Covid, can raising repo rates bring down prices?

If the cause of the current inflation spike was excessive demand — “too much money chasing too few goods” — then raising interest rates could have helped matters. Higher interest rates would have weaned off a sufficient number of people away from spending and into investing thus bringing down the price level.

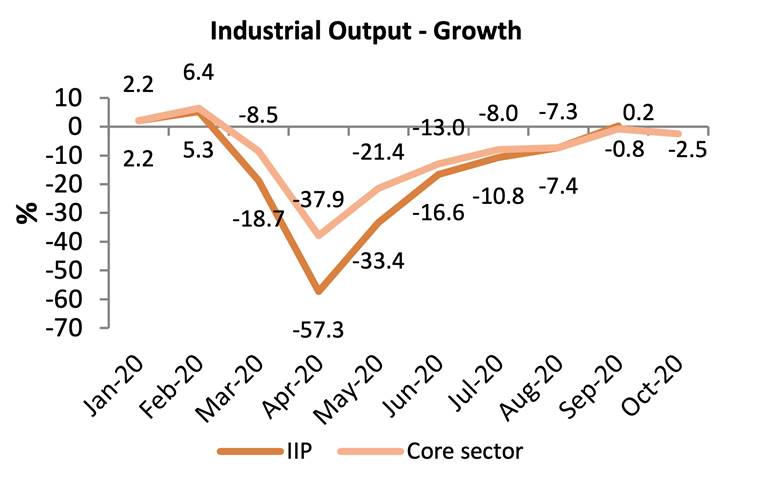

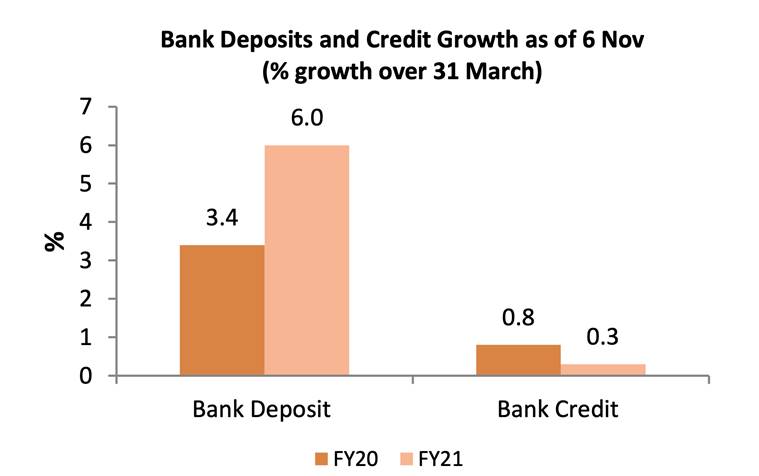

But that is not happening at present. Industrial growth is almost non-existent (see Chart 4) and credit off-take is anemic (see Chart 5). Capacity utilisation in firms is low and they are laying off employees to cut back costs.

Moreover even raising repo rates or cutting them typically takes some time — at least a quarter — before influencing the market interest rates that you and I get paid.

That is why central banks are more bothered about managing people’s expectations of future inflation instead of reacting to monthly inflation movements.

If raising interest rates is not effective, then what is the way to cool down prices?

Coronavirus Explained

Click here for more

The RBI underscores the need for “proactive supply management strategies. “Further efforts are necessary to mitigate supply-side driven inflation pressures,” it states.

Who will do this? Of course, the government. The RBI is already doing the best it can — not raising interest rates even when all types of inflation parameters are off the charts.

A year down the line, India still cannot be characterised as facing stagflation. While GDP growth is expected to rebound, persistently high inflation is now becoming a worry that cannot be brushed aside as seasonal or transient.

Stay safe,

Udit

An Expert Explains: Nature of economic recovery in India

Source: Read Full Article