The mosque’s real name is where its history aligns with the shipping merchants of the Kutchi Memon community, known for their business acumen.

Written by Mohammad Ibrar

Nasser Ebrahim is a treasure trove of stories. Sitting in his Bentinck Street store in Central Calcutta (Kolkata), he often reads up on things to keep himself occupied. The sexagenarian is also one of the last few members of Kutchi (Cutchi) Memon community that arrived in Calcutta over a century ago to foster their shipping trade with Burma, Java and other regions and made the city their own. Over time, the fairly strong Kutchi Memons acclimatised in Calcutta, added their cultural footprint, and then as quickly as they came, left for better opportunities. Now just 200 families of their fraternity call the city their home.

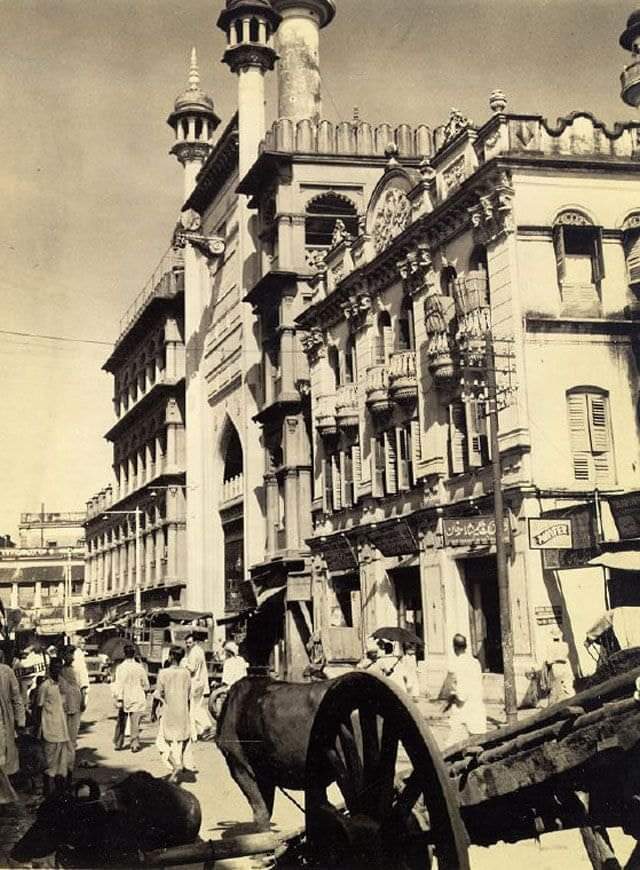

The Nakhoda Mosque, which stands at the intersection of Rabindra Sarani and Zakaria Street, is known better by its name ‘Bada’ or ‘Badi’ masjid primarily due to its sheer size, grandeur and the cultural impact it has had on the psyche of the Kolkata Muslim community. So much so that it is the first place where the Eid prayers happen in the city. But the mosque’s real name is where its history aligns with the shipping merchants of the Kutchi Memon community, known for their business acumen.

Sitting in his store, the wizened Ebrahim recollects the history of his ancestors who arrived in Calcutta over a century ago from Bhuj, Gujarat. “They arrived here planning to continue their shipping business. Hence the large mosque which they built for themselves and the larger Muslim community was named Nakhoda Mosque for the word Nakhoda means the captain of a ship.”

The mosque is present in the old part of Calcutta, not so far from the Jorasanko Thakur bari, the ancestral home of the Tagore family. And much like the Tagores, the mosque leaves a mark on the Calcutta skyline with its bulbous dome and towering minarets. Described by the West Bengal tourism website as “the largest Masjid in the city of Kolkata” it is said that it was built through the financial support of a Kutchi Memon, Abdar Rahim Osman, in 1926.

It was not just Osman, Ebrahim adds, but every other member of the mercantile community who collected money to build the mosque. “There used to be a small mosque here which was ‘martyred’ and this structure was then developed.” He says even the road where the mosque stands is named after a powerful businessman Haji Zakaria, another Kutchi Memon. “Such is our impact.”

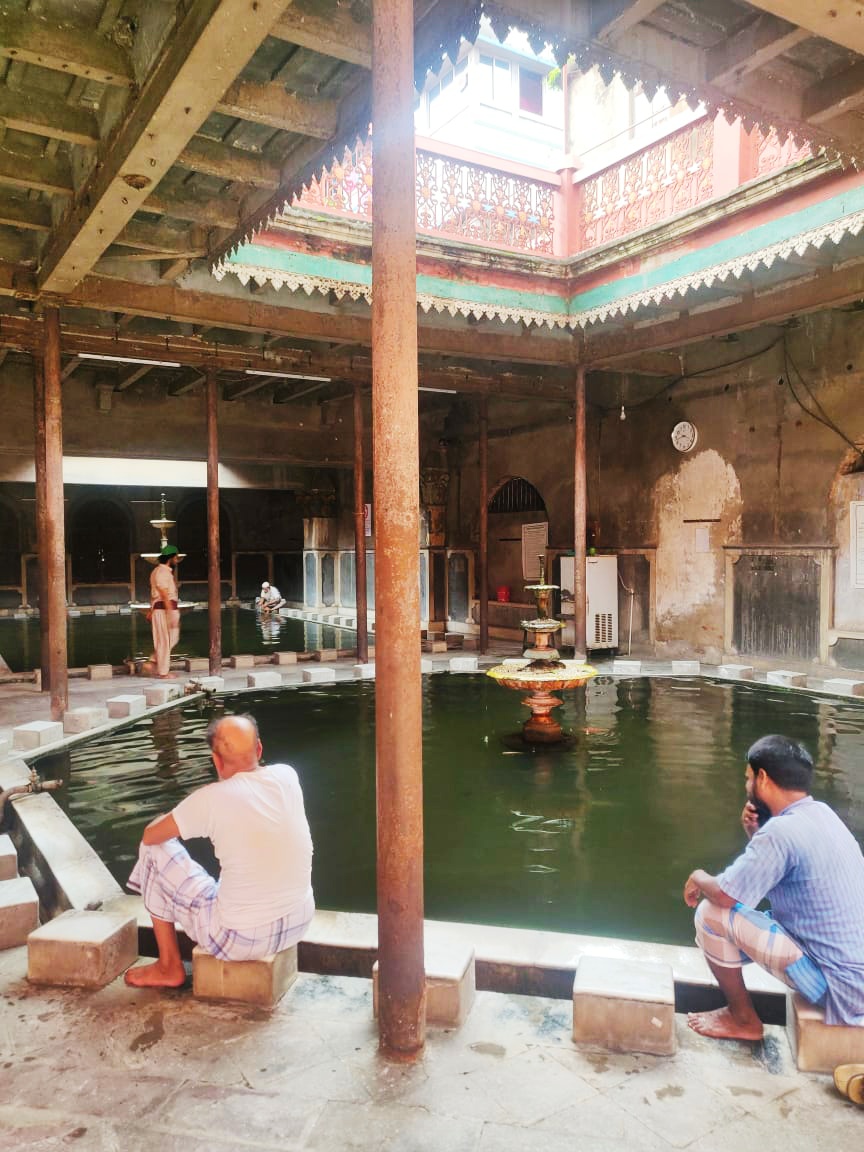

According to West Bengal Tourism, “The gateway to the Masjid resembles the Buland Darwaza at Fatehpur Sikri. For its construction, granite stones were brought from Tolepur. Inside the Nakhoda Masjid, there is a fabulous exhibition of ornaments and art.”

The mosque has a unique blend of Indian and Saracenic architectural features with three large domes, two minarets as tall as 151 feet, and 25 smaller minarets with lengths varying from 100 to 117 feet.

Iftekhar Ahsan, founder of Calcutta Walks, believes the mosque has been a huge influence as “it is a magnificent structure and has had an impact on solidifying the location of the Muslims and also their culture”. “The mosque harks back to a time when Calcutta was an extremely prosperous city and where the Muslims were also prosperous and it shows in their worship house,” he adds.

Ahsan explains that “while the mosque’s gate has been designed like the gate of Akbar’s tomb in Sikandra but the capitals are Corinthian. So it is a great addition of Greco-Roman features in a mosque. Additionally we see a large courtyard which is reminiscent of Bengali homes.”

Most in the Kutchi Memon community hold the mosque close to their heart and consider it part of their impact on Calcutta. “The upkeep of the mosque is still done by the Kutchi Jamaat members who are trustees of the structure well into its 95th year. When the mosque was constructed, the area was but a bustee where migrant Muslims reside. This mosque became the focal point around which Calcutta’s Muslim culture grew and developed,” explains trustee and jamaat member Mohammad Zahid Ahmed, adding that to this day, when a majority of Kutchi Memons have migrated to other places, the community still manages the upkeep of the structure. “In fact, its is one of the few mosque which does not identify with any sects within Islam. We are not rigid unlike some other mosques. We were comfortable with the local people and often helped the people of the city.”

Ebrahim adds that it is their beliefs in a just and equal system that ensures the Kutchi community’s mosques do not belong to any particular school of thought in Islam. “People from the Hanafi to the Ahl-e-Hadith come here and pray. This mosque belongs to all; just as it always did since the construction of this mosque. It reminds us of our family and how much of an impact we have had on Calcutta and other cities in the world.”

The Kutchi Memons consider themselves to be “converts from Hinduism” and attribute their business acumen to their source stock: the Hindu Lohanas. From Kochi to Secunderabad to Dar-es-Salaam in Tanzania the community survives on this business acumen.

Despite their success and impact on Kolkata, the community eventually left the city. The migration of the community from their adopted home began when the shipping industry took a beating and multiple communal riots in Calcutta in the early 20th century troubled the business folk of the community. Ahsan also attributes the migration to the “decline of Calcutta started after the capital was shifted to Delhi”.

“Many left after the 1947 Partition to Karachi; while others moved to countries like Mauritius and Kenya and settled there. One of our own, Sir Abdul Razzak Mohammed, who happens to be my grandfather, was born in Calcutta before leaving for Mauritius where he eventually became the Lord Mayor of Port Louis and the Deputy Prime Minister,” says Ebrahim.

The jamaat member however concedes that in their effort to give back to the people in Calcutta, they have lost some of their own. “We are culturally no longer different from the other Muslims in the city. Most of us have forgotten how to speak Gujarati. Except for a few traditional practices which are also dying down, we seem to have no marker which makes us unique from the cultural mix of Calcutta’s Muslims which includes people from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and rural Bengal. Most of our members who left Gujarat at the turn of the 19th century decided to settle in multiple cities in the world where they still have their own jamaats. But while we may have lost certain features of our culture, we are delighted that the mosque made by us will soon be a century old,” says Ebrahim.

There is a passage in the All India Cutchi Memon Federation’s souvenir in 1993, that sums up what the community feels about leaving Kolkata. “They lived up to their title ‘Memons – the blessed ones’ wherever they went. Masjids, madrassas, musafirkhanas, cemeteries scattered all over proclaim from housetops the acts of philanthropists… Those that have remained behind in India have only to play their part in the reconstruction of their motherland, and have to contribute their might towards greater prosperity of the community in particular and the country at large.”

Source: Read Full Article