Earlier this month, a team of over 1,000 birdwatchers wrapped up field surveys of the ‘Kerala Bird Atlas’, perhaps Asia’s largest citizen science bird project that will throw light on the distribution of birds in the state and more importantly chronicle the impact of habitat destruction and climate change on the avian species.

Over the past five years, they climbed steep cliffs in risky, rainy weather and navigated swollen rivers. They confronted angry herds of elephants in deep jungles and had their legs sucked by leeches. On multiple occasions, they were almost roughed up by locals who didn’t take kindly to their presence. They spent money out of their own pockets to traverse large distances on weekends and off-days to pursue what they all believed was an important, far-reaching mission — document the bird diversity in Kerala.

Earlier this month, a team of over 1,000 birdwatchers wrapped up field surveys of the ‘Kerala Bird Atlas’, perhaps Asia’s largest citizen science bird project that will throw light on the distribution of birds in the state and more importantly chronicle the impact of habitat destruction and climate change on the avian species.

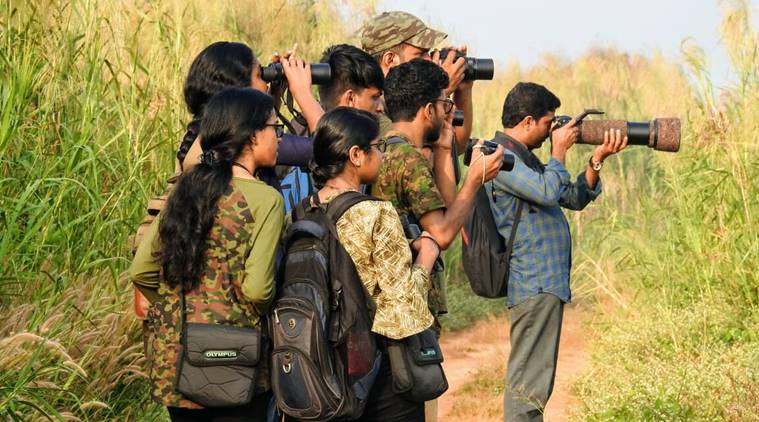

Volunteer birdwatchers, linked to natural history societies and ornithology clubs across the state, teamed up with forest officials to scan nearly 10% of Kerala, surveying 4,000 locations over 600 days. Locations were surveyed during both dry (Jan-March) and wet (July-Sept) seasons though coverage during the monsoons was affected by back-to-back floods in 2018 and 2019 and the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic.

Every team, assigned a specific location, had a minimum of two and a maximum of five members, usually headed by a senior birdwatcher. In protected areas and reserve forests, the teams were accompanied by forest watchers who are better acquainted with the lay of the land. All the teams had one goal: document the birds they see and hear with the help of audio and video evidence.

“Bird atlases of similar kinds have been done in western countries. However, to execute such a project in a mountainous, tropical state with some of the most impenetrable forests in the world is a commendable job,” said Dr PO Nameer, special officer at the Academy of Climate Change Education and Research at Kerala University and a state-level coordinator of the atlas project.

Dr Nameer said he got introduced to the world of birds over three decades ago through the Malayalam-language book ‘Keralathile Pakshikal’ (Birds of Kerala) by Prof KK Neelakandan who wrote under the pen-name of Induchoodan. The book belonged to his brother who was interested in birdwatching. “One day, I happened to read a few pages and my interest in birds began,” he said.

Over the years, he acquainted himself with the birdwatching fraternity across Kerala which grew in size and strength with the advent of technology and social media.

“We have annual gatherings in many places and when we met in 2014, the idea of committing to a bird atlas was put forward. Our confidence in attempting the project was due to two reasons: the active birdwatching community in the state and the development of the app Ebird,” he said.

With a survey this expansive and researchers handling large, voluminous amounts of data, having a mobile application like Ebird was critical to the project, stressed Dr Nameer. The app simplified the process of recording bird sightings into the database and helped to detect errors while manually feeding the data.

“For example, if I happen to record an unusual species in a certain area and if that bird is not commonly seen in that area, then the district-level reviewers will receive a notification of the entry on Ebird. They will then cross-check the entry made by the volunteer and send him/her a query asking for more details. The checking is done not only for the characteristics of the species, but also for the number of individuals of the species recorded through the app,” he said.

For 45-year-old Vishnupriyan Kartha, who led several field trips in parts of Ernakulam and Idukki districts in central Kerala, the bird atlas project combined several of his interests — love for birds, trekking in jungles, interacting with like-minded people and a rush of adrenaline — things he wouldn’t get from his regular job at a private university in Kochi.

Like the time his team came face-to-face with a herd of wild elephants earlier this year during a field survey in the forests near Ennakkal station in Ernakulam district. They were forced to retreat when one of the elephants moved towards them, perhaps curious of their presence. The team had to wait for a long time for the herd to pass through the area before they could return to the forest base. At another time, said Kartha, during a trip to Illithodu, they encountered herds of elephants and bisons moving together through the forest. “We had to climb down the hill, cross a few streams and take a much longer route to the location that we had to go to. It was challenging, but it was also thrilling,” said Kartha.

For Hari, an avid birder who led survey teams in Pathanamthitta district, the challenge came interestingly not from wild animals, but people. “Once, I was surveying a residential area and I was stopped by the locals who looked as if they were in a mood to beat me up. Apparently, a girl in that neighbourhood had eloped with a guy and these people thought I was in cahoots with that guy, scoping out the area to see if it was safe for them. Fortunately, I had a newspaper clipping of the bird atlas and a few youngsters there understood what I was trying to do,” he said.

Of course, these tricky challenges and the physical constraints of undertaking the surveys are subsumed by the sheer joy of spotting a rare or uncommon bird species. Kartha said he experienced one such moment in January this year when his team came upon a pair of Sri Lankan frogmouth, an odd species that looks like a cross between an owl and a nightjar and endemic to the Western Ghats in India and Sri Lanka.

“We were visiting a region near the power-house of the Idamalayar dam. This place was ravaged by the 2018 floods and there were huge boulders everywhere. It’s a very challenging terrain and as we were walking back, we came across a tiny thicket where we saw a pair of the Sri Lankan frogmouth (Batrachostomus moniliger). We had never expected to see that bird there because they are normally found in the Thattekkad region. It was a real surprise,” said Kartha.

During another survey in a forest fringe area near Athirappilly in Thrissur district, Kartha said his team was excited to spot two pairs of the beautiful spangled drongo (Dicrurus bracteatus), a species uncommon in the area. Adult birds of this species have dark red eyes with an all-black body and a long, cleft tail with a curvy end.

Praveen V, a freelance sales consultant who assumed the role of lead birder in quite a few surveys of the atlas in Palakkad district, said 90 per cent of the species they spot in a particular area would be on expected lines. “There’s a lot of planning involved and experienced birders would have a rough idea of what species we might encounter in a particular location. But there have been instances where we have found birds that we didn’t expect to be in a certain area,” he said.

“Like, for example, when we had gone to a region near the Chakolas Estate in Malampuzha, we saw a Nilgiri Wood-Pigeon (Columba elphinstonii) for the first time. Now, this is a bird usually found at an altitude of 800 m above sea level. But we spotted it at an altitude of 400 m above sea level. We initially thought it was some other bird. But my colleague took a photograph and when we came back and checked with experts, they confirmed it was a Nilgiri Wood-Pigeon,” he said, referring to a species, which according to eBird, inhabits wet forests in hilly and montane areas and occasionally descends to feed on the ground.

Nuggets of information like this are central to the idea of the atlas in preparing a comprehensive registry of bird species and a baseline data that can enable comparisons with future surveys. Since birds are also viewed as indicators of changes in ecological conditions, the insights gained from the atlas can help point to urgent course-corrections required in a particular location.

With the conclusion of surveys, researchers are now engaged in compiling and analysing the data recorded so far with an aim to publish the first draft of the atlas by the end of 2020 and a detailed report to follow by next year. While some of the district atlases have been formally released already, an online dashboard created in github showing locations and the species sighted there is available for public viewing too.

(Deborah Thambi, an intern with indianexpress.com, contributed to the reporting.)

? The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest India News, download Indian Express App.

Source: Read Full Article