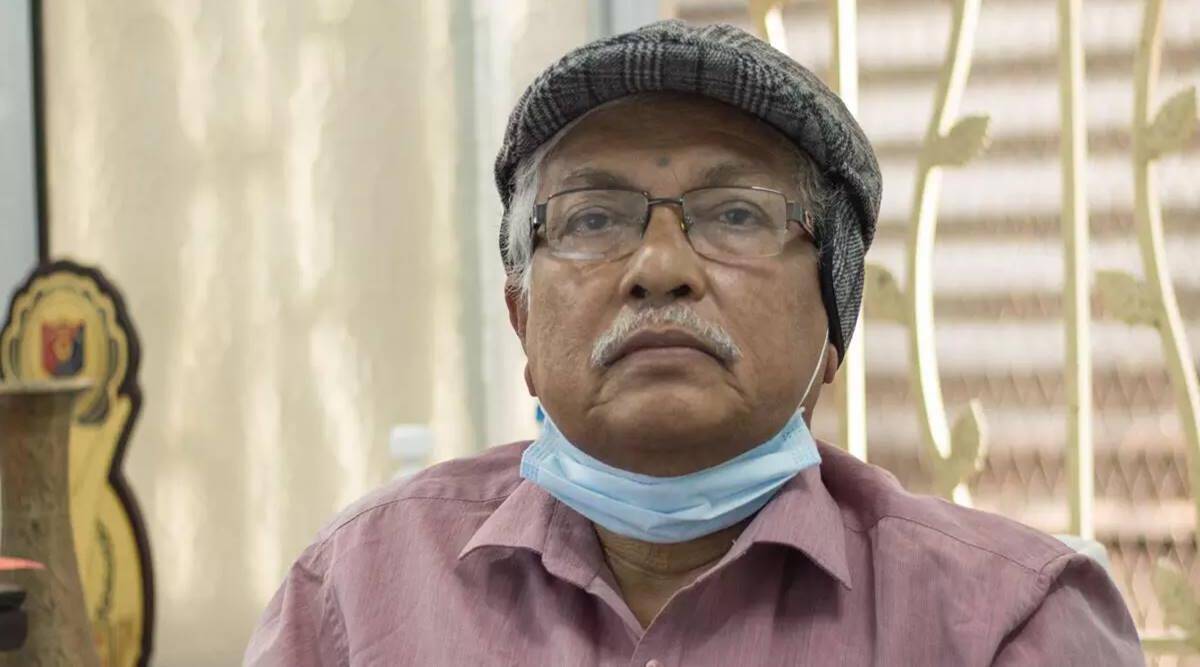

Smarjit Jana nudged governments, aid agencies, NGOs and activists into respecting the choices made by sex workers

Written by Toorjo Ghose

Smarajit Jana’s passing away last week marked a distinct stutter in our progress towards social justice and the vanquishing of the Covid pandemic. When I first met Jana in 2000, I was a social welfare doctoral student based in the United States, and he was a legend in the field of public health. He had helped start the iconic Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee (DMSC), a collective of sex workers in Sonagachi, Kolkata, that had forced the world to sit up and take notice.

At a time when the HIV pandemic was raging across the globe, and so-called “prostitutes” were being indicted for being a key population spreading the disease, DMSC had reduced infection rates in Sonagachi, Kolkata, one of the busiest red-light areas in the world, to less than 1 per cent.

Jana and DMSC had started erasing the word “prostitution” from the popular lexicon, replacing it with “sex worker”, and demanding of us a complete re-orientation towards sex, work, and choice. As he would often argue to audiences comprising representatives of entities such as the Indian Government, the UN, and the World Bank, choices made by poor women to combat poverty needed to be supported, not criminalised. In the field of public health and HIV, this was a Kuhnian paradigm shift.

The realisation that people’s choices around engaging as sex workers could simultaneously be constrained by poverty, and be supported in order to defeat it, transformed the battle against HIV. Marginalised community members became collaborative partners in HIV initiatives instead of targets of intervention, and agents of change instead of victims who needed to be rescued.

Under the guidance of Jana and DMSC, the Indian government partnered with the Gates Foundation to implement these lessons nationwide through the Avahan Project. Jana spent time in Bangladesh, shepherding the country’s HIV interventions at the height of the epidemic.

While public health curricula across the world now include mandatory training in community empowerment, the utilisation of peer counsellors, the establishment of community action boards, and the development of micro-banking cooperatives, DMSC and Jana were often the first to introduce these notions, and the methods to implement them successfully.

DMSC’s reach eventually extended well beyond the field of public health. The question of whether sex work constitutes legitimate labour or human trafficking has fueled arguments in the legal, feminist, philosophical, labour, and activist milieus for a long time. Jana and DMSC made a critical intervention in this debate through the deceptively simple expedient of asking sex workers themselves to weigh in on it. And weigh in they did.

Galvanised by DMSC’s work in India, sex workers across the world demanded a voice in discussions concerning their lives. While I have seen Jana present in various fora over the years, never was he more animated or empathetic than before an audience of sex workers.

Recently, in a small living room in Philadelphia, USA, I watched as he infused a group of women and transgender sex workers with immense excitement at the possibility that sex workers could indeed shape their own lives. Watching him in these settings, I was continuously reminded of the model that DMSC has become for sex workers all over the world. While it has been designated as a best practices program by the World Bank, the real wonder lies in the fact that the global sex work movement often takes its cues from India.

Jana’s efforts eventually led to the establishment of the All India Network of Sex Workers, representing hundreds of thousands of sex workers from thirteen states in India, and a national advisory body that has been entrusted by the Supreme Court of India to safeguard the rights of the sex work community. Knighted by Kolkata’s sex workers – he was affectionately known simply as “Sir” in the community –Jana is now regarded as the father of the sex work revolution in India.

I take solace in some of Jana’s own words: “Pandemics destroy individual lives, but they cannot destroy social movements.” We will miss you immensely, Sir.

The writer is an associate professor, School of Social Policy & Practice, University of Pennsylvania

Source: Read Full Article