When the Naxalite movement took flame in Bengal in the late Sixties, he was drawn towards it, working at its fringe till disillusionment set in when he realised fallibilities of the leaders he had encountered.

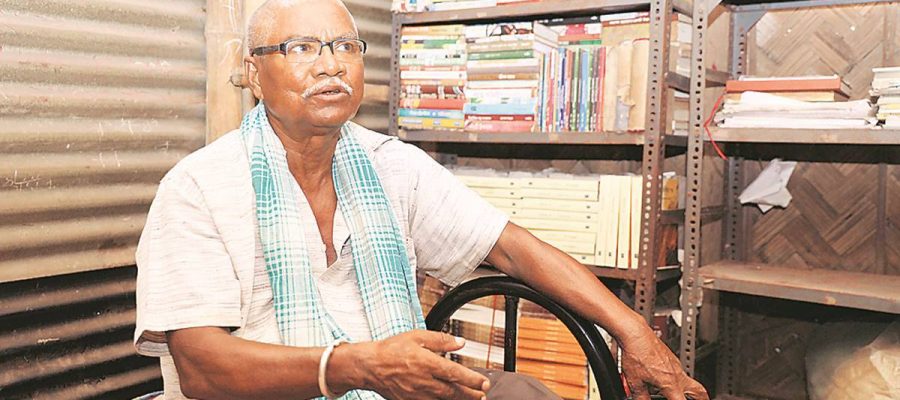

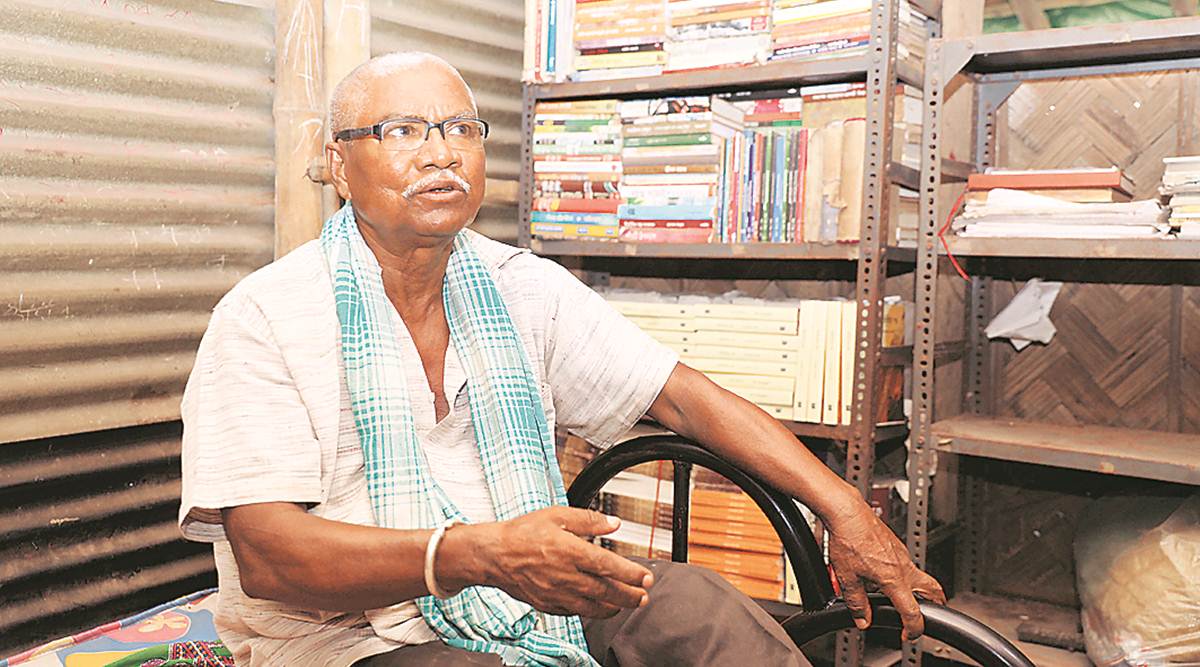

In his late 20s, disenchanted with the Naxalite politics that had once appealed to him for its promises of equality, when Manoranjan Byapari decided to start life afresh, the only work that he could find was that of a rickshaw puller. “Every day, I would follow my passengers’ directions and ferry them to their destinations, while keeping an eye out for potholes on the road or for oncoming traffic. You could say, I followed their instructions but tempered it with my intuition. That is what I intend to do this time, too,” says the noted Dalit writer, who will stand for elections as a Trinamool Congress candidate from the Balagarh constituency in Hooghly district in the upcoming Assembly elections in West Bengal. Fittingly, soon after his candidature was declared, the first campaign poster of the 70-year-old chairperson of the Dalit Sahitya Academy in West Bengal featured the slogan “Rickshaw ebar Bidhan Shabhay (The rickshaw is now headed for the Vidhan Sabha)”.

Byapari, who has emerged as a powerful voice in Dalit literature over the last decade, is no stranger to politics. Having moved to West Bengal in 1953 as a political refugee from what was then East Pakistan, his hardscrabble life has seen him work in tea shops and dockyards, as a dom (a cremation-ground caretaker); a rickshaw puller, and, as a cook. When the Naxalite movement took flame in West Bengal in the late Sixties, he had felt drawn towards it, working at its fringe till disillusionment set in when he realised the fallibilities of the leaders he had encountered. Since then, the writer of acclaimed Bengali novels such as Itibrittey Chandal Jibon (2012, Interrogating My Chandal Life: An Autobiography of a Dalit, translated by Sipra Mukherjee into English and published by Sage in 2019), Batashe Baruder Gondho (2013, There’s Gunpowder in the Air, translated by Arunava Sinha into English and published by Eka in 2019) has steered cleared of any political affiliations, writing instead about the experiences of caste outcasts like him in his novels and short stories.

What changed his mind this time, says Byapari, is the “bibhajaner rajniti (divisive politics)” that he sees in Bengal today, perpetrated by the main opposition, the BJP. “You can feel the toxicity in the air. What is happening in Bengal is unprecedented and it needs to be countered. This is a politics of violence — in words and action — and if we don’t protest, it will land our own people in detention camps as ‘outsiders’,” he says, referring to the National Register of Citizens and the Citizenship (Amendment) Act.

Which is why, when West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee reached out to him, he did not hesitate to accept her offer of candidature. “I have seen her work for Namasudra people like me, for the Matuas [a Scheduled Caste community] over the last decade. When she told me, ‘Dayitto nite hobe (You have to take responsibility)’, I had no reason to say no,” says the writer.

Ever since the news of his candidature was announced, his house in Mukundapur on the outskirts Kolkata has been overflowing with party workers and well-wishers dropping by to discuss his new role. “I have always spoken up against injustice, about the treatment that people at the bottom end of the caste hierarchy meets with, the lack of opportunities that never lets them flourish. At the end of the day, the common man wants very little — he wants khadya, bastra, shiksha and shamman (food, clothes, education and respect). When I go to meet the people of Balagarh, this is what I intend to tell them — that I will be their voice against injustice and discrimination; that I will be a rickshaw-puller all over again, carrying out their mandate but tempered by my experience and intuition,” he says.

Source: Read Full Article