With lunar landscape, churches, open-air museums and surreal volcanic eruptions, the Turkish region holds one under a spell.

The road stretched for miles, straight and unwavering, with lush-green carpets of grass and nondescript hillocks on either side. Pretty, but soporific and rather underwhelming, considering it was Turkey’s historic Cappadocia region, known for its extraordinary geographical formations. But it changed within a blink, and on either side rose masses of pale-brown mounds and towers, as if carved by unseen hands, and presented a jaw-dropping picture. The transition from dull to dramatic had taken just a few seconds and the landscape suddenly felt lunar, and brought back childhood memories of watching Star Trek. Not the new ones with CGI effects but the original series.

As the road rushed past more and more formations, each different and more dramatic than the previous, the sense of wonder only heightened. So much so, that by the time the vehicle swept into the little town of Göreme, the overwhelming urge to get close to the structures was all-consuming. And it didn’t take long. The main thoroughfare, flanked by colourful souvenir shops, boutiques, cafés and restaurants, ended at the Göreme Open Air Museum, a Unesco World Heritage site. It was a stunning sight: endless stacks of towering pointed rocks, carved by wind and water, many of which had been cut out into cave-like structures and they were human settlements going back a few thousand years. I half expected Captain Kirk and Spock to appear from behind one of them.

Before I got lost in the maze of structures, my guide gave me a brief outline. Spread across central Turkey in the Anatolian plains, Cappadocia was subject to volcanic eruptions, perhaps 60 millions years ago, which left it resembling the moonscape; the basalt and tuff (a porous rock formed through packed volcanic ash) further moulded by erosion into fantastic structures, called fairy chimneys, whose shapes differed from place to place. In the stark landscape, human history went back a few millennia; in several locations, it had led to cavern architecture and settlements in almost gravity-defying locations.

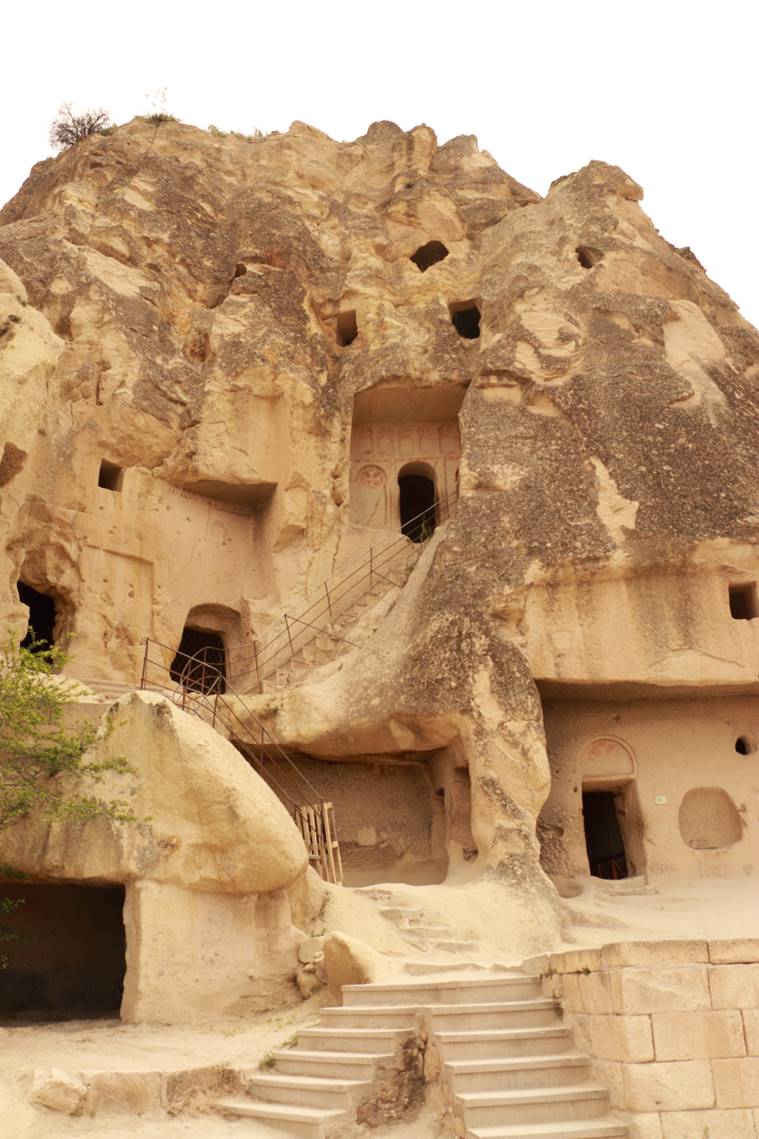

In Göreme’s case, it extended over a staggering area of more than 100 sq. km, but was known for what its earliest settlers designed and left behind. The highlight was the vast monastic complex with several different refectories and beautiful rock-cut churches going back to the 10th, 11th and 12th centuries. Almost immediately after the entrance was a nunnery, with multiple floors comprising living rooms, kitchen and dining hall, with a church on the third floor. The rest of the complex was dominated by several churches, a unique feature of which was the evocative frescos on the interior walls and ceilings. A series of steps led to Elmali Church, inside which a vaulted structure stood out in the main section and had vivid coloured frescos depicting scenes from Christ’s life, the Bible and other stories. St Barbara’s Chapel, on the other hand, had a cruciform plan and beautiful geometric patterns, motifs and mythological symbols painted in red on its walls. Other prominent churches included the Snake Church and Dark Church, possibly because of a dark, winding tunnel used for access. A few kilometres north of Göreme was Pasabag, which was spectacular in a different way. Set in the middle of wide open spaces, it was filled with surreal fairy chimneys that lay spread out. The tuff and formations here were entirely different – straight columns topped with caps, like large mushrooms and toadstools, making for a rather striking picture. A winding and sloped path led to the centre of a cluster of tuff cones of varying heights and dimensions, rising up to 10-15 mts; some had even split into dramatic multiple cones. There were several dwellings going back as far as the 5th century. Also called Monk’s Valley, these structures were believed to have been inhabited by hermits who carved the chimneys and lived inside, in seclusion.

Almost adjacent to Pasabag was Zelve Open Air Museum, one of the largest clusters of conical-shaped structures. Arrayed over an undulating landscape, Zelve had an amazing density of sharp, pointed formations and was supposed to have housed one of the largest ancient communities. Inhabited between the 9th to 13th centuries, Christians moved here during the Arab and Persian invasions and are believed to have established the first seminaries to train priests. Called the cave town, the entire area, with steps and narrow inclined paths snaking up and down crests and valleys, was replete with dwellings, religious structures (churches and mosques) and community buildings, including a winery and a grindstone mill. Interestingly, this was one of the most successful settlements, with people living here till as recently as 1952, when they had to be moved out due to the dangers of erosion. Clambering up and down the steps led to the Deer Church, with its faded but beautiful frescos, the Church of Grapes and the Church of Fishes.

And so it went, the surreality only increasing with every stop. Even though fairy chimneys were everywhere, quite literally, fatigue refused to set in. East of Zelve, the winding road passed through Dervent valley, also called Imagination Valley, because it was filled with natural sculptures which resembled such eclectic things as the Virgin Mary holding the Infant Jesus, a dancing couple, and animals such as a panda, a seal, a dolphin, a camel, a bear, deer…as the name indicated, all it required was imagination. I wouldn’t even have flinched to hear, “Beam me up, Scotty!”

But as the sun dropped down towards the horizon, I perched against a precarious drop in Red Valley with the yawning geographic basin in front of me filled with accordion-ridge formations stretching out as far as the eye could see. The whole valley glowed a beautiful rust-orange, both the earth and the sky taking on shades in the same colour palette. People were scattered across the ridges but watched in silence. And, then, as if giving up a final hurrah, the sun sank below the horizon line, pulling darkness behind it like a curtain. As shows went, it was a spellbinding one. Soon, there was nothing to show for it at all, except flashes of images, like a vivid psychedelic dream. Not for nothing is Cappadocia called a rocky wonderland, a whimsical fairy tale.

Anita Rao-Kashi is a Bengaluru-based freelance travel writer.

? The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Eye News, download Indian Express App.

Source: Read Full Article