In Afghanistan, where ethnic faultlines run deep and come in the way of nation-building, the Taliban takeover raises questions, especially on the future of the not-so-dominant groups.

The Royal Salute was Afghanistan’s first national anthem, an instrumental adopted in 1926 when Amanullah Khan the Amir became King in the seventh year of his rule.

In the 95 years since, the country has had five other anthems, in tune with the change of regimes and rulers. And a 5-year period of no anthem. That soulless period began in 1996 when the Taliban first seized power. With their ban on music, the Qal’a-ye Islam, Qalb-e Asiya (Fortress of Islam, Heart of Asia) disappeared.

A battle song from 1919, it had been the anthem since 1992 when the mujahideen toppled Mohd Najibullah. The anthem returned after the Taliban’s ouster in 2001 following the 9/11 strikes.

The anthem, the Constitution

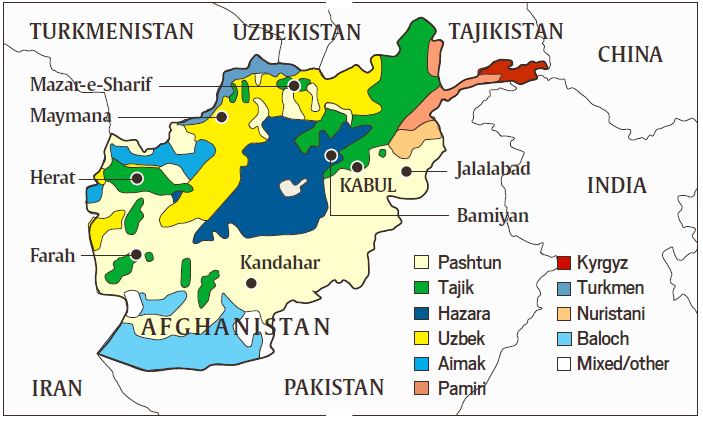

Ethnicity runs deep in Afghanistan and its diversity, ironically, has also been its undoing with loyalties divided and fierce, and affiliations so clear that they come in the way of nation-building. It is also one reason why wars over decades spawned warlords and turfs demarcated on ethnic lines.

The Constitution of 2004 and the national anthem referred to 14 ethnic groups. Article 4 stated that the nation of Afghanistan shall comprise “Pashtun, Tajik, Hazara, Uzbek, Turkman, Baluch, Pachaie, Nuristani, Aymaq, Arab, Qirghiz, Qizilbash, Gujur, Brahwui and other tribes”. And Article 20 made it clear: “The national anthem of Afghanistan shall be in Pashto with the mention of ‘God is Great’ as well as the names of the tribes of Afghanistan.”

So the Milli Surud identified the tribes of the land: “This is the country of every tribe, the land of Balochs and Uzbeks; of Pashtuns and Hazaras; of Turkmens and Tajiks. With them, there are Arabs and Gujjars, Pamiris, Nuristanis, Brahuis, and Qizilbash; also Aimaqs and Pashais.”

The predominant Pashtuns

Among the ethnic groups, the Pashtuns are the largest, estimated to be 40%-42% of the country’s 3.8 crore population. Pashto and Dari are the official languages.

The Pashtuns, who are mostly Sunnis, have long been the dominant group – in recent times, from the Taliban chiefs who took Kabul in 1996 to Hamid Karzai who succeeded them in 2001 to Ashraf Ghani who ruled from 2014 till he fled last Sunday.

Concentrated in the south and east of the country, the Pashtuns are scattered across the country, from the south of Amu Darya to the borders with Pakistan and beyond.

Bound by the code of Pashtunwali, they do not recognise the Durand Line that divides them on either side of the rugged border. ? Express Explained is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@ieexplained) and stay updated with the latest

The Tajik adventures

The ethnic Tajiks, who form the majority in neighbouring Tajikistan, are the second largest group in Afghanistan – it is estimated they make 27% of the population.

They have never really held power. In January 1929, a Tajik soldier-turned-bandit, Habibullah Kalakani, known to most as Bacha-i Saqao or the son of a water carrier, showed up in Kabul, and Amanullah Khan fled, handing charge to his brother who surrendered after two days. Kalakani’s brief rule ended in October that year and he was executed the very next month.

In 1992, after the fall of the Najibullah regime, a civil war engulfed Afghanistan. Ahmad Shah Massoud, a Tajik commander from the Panjshir Valley who had become the nemesis of the Soviets, emerged as the mujahideen strongman and began calling the shots in Kabul.

Burhanuddin Rabbani, also a Tajik, from Badakhshan in the far northeast, became President. His was the government that the world recognised until 2001 even after it was forced into exile following the Taliban takeover of Kabul in 1996 – only Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and the UAE recognised the Taliban rule.

The Tajiks are the predominant ethnic group in Herat in the west and Mazar-e-Sharif in the north. They are present in sizable numbers in Kabul and the provinces to its north.

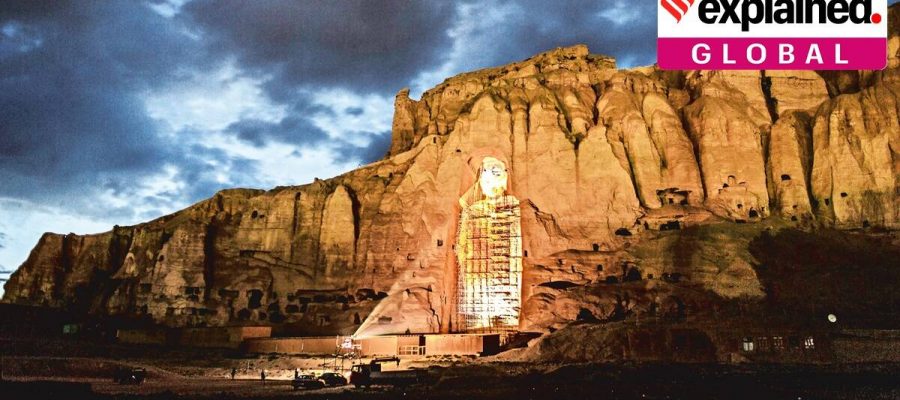

The Buddha grounds militia

The Hazaras are the third largest ethnic group, accounting for 9%-10% of the population. Most are Shias and live in Hazarajat in the central highlands – Bamiyan, where the Taliban destroyed the Buddha statues in March 2001, is the main city of the region.

The Hazaras, who are said to be of Turkic or Mongol origin, have had a troubled past with Kabul. In the months that followed the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan in 1989, Hazara groups came together to form their own militia called the Hizb-i-Wahadat, which later split over the issue of joining forces with Massoud and Rabbani.

In March 1995, Wahadat faction leader Abdul Ali Mazari and his colleagues were invited to talks by Taliban leader Mullah Burjan near Charasyab. He was abducted, tortured and killed. The Taliban claimed Mazari attacked them while being taken to Kandahar. He was buried in Mazar-e-Sharif, then controlled by Uzbek warlord Abdul Rashid Dostum.

At Rumi’s airport

Mazar, the key city in the north, was until now under the control of Dostum and his Uzbek troops – the Hairatan crossing on the border with Uzbekistan is barely an hour’s drive from Mazar. But the Uzbeks are not the predominant group in the city – they are outnumbered by the Tajiks and Pashtuns. The city is also inhabited by the Hazaras and Turkmen.

Mazar is the capital of Balkh and its airport is named after Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Balkhi who we know as Rumi, the 13th century poet, scholar and mystic. The city also houses the Blue Mosque which the Sunnis believe contains the tomb of Hazrat Ali – Shias maintain that he rests at the Imam Ali shrine in Najaf, Iraq.

Herat and provinces near the Iran border are home to Shias – it is estimated that 10% of the country’s population are Shias.

The minorities, and questions

With the Taliban now in complete control of the country, questions are already being asked about their likely treatment of the ethnic groups that make the country, especially the minorities.

What has heightened fears is that leaders of ethnic groups have either fled or are now forced to negotiate with the Taliban – Uzbek warlord Dostum, Herat strongman Ismail Khan, Hazara leader Karim Khalili, and ethnic Tajiks Amrullah Saleh and Atta Muhammad Noor.

The anthem mentions 14 ethnic groups, but there are many more who form the minorities – apart from the Aimak, Turkmen, Baloch, Pashai, Arab, Nuristani, Brahui, Pamiri, Gurjar. AS for Hindus and Sikhs, though their numbers have dwindled over the years with most emigrating – one estimate put that total at 1,350.

Ever since the takeover, the Afghanistan flag is being lowered across provinces, replaced by that of the Taliban. If the ban on music returns, the anthem too will disappear. That anthem which stitched together different ethnic groups for “the country of every tribe”.

Sinha was in Afghanistan to cover the rise of the Taliban in 1995, their takeover of Kabul in 1996, and their ouster in 2001, for The Indian Express.

Source: Read Full Article