Health authorities have been warning of a possible third wave of Covid-19 infections. What defines a wave in an epidemic, at national and regional levels? How likely is a third wave, and will it be severe?

Get email alerts for your favourite author. Sign up here

Having failed to adequately prepare for the second wave of coronavirus infections, officials and health authorities are now routinely warning people of the possibility of a third wave. It started earlier this month with the Principal Scientific Advisor K VijayRaghavan calling the third wave “inevitable” even though its timing could not be predicted. VijayRaghavan added a caveat two days later, saying a third wave could be avoided through “strong measures”, but several others have issued similar warnings in the last couple of weeks. Local administrations and some hospitals have already begun ramping up their infrastructure in anticipation of a fresh surge in cases after a few months.

What is a wave in an epidemic?

There is no textbook definition of what constitutes a wave in an epidemic. The term is used generically to describe the rising and declining trends of infections over a prolonged period of time. The growth curve resembles the shape of a wave. Historically, the term wave used to refer to the seasonality of the disease. Several viral infections are seasonal in nature, and they recur after fixed time intervals. Infections rise and then come down, only to rise again after some time.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

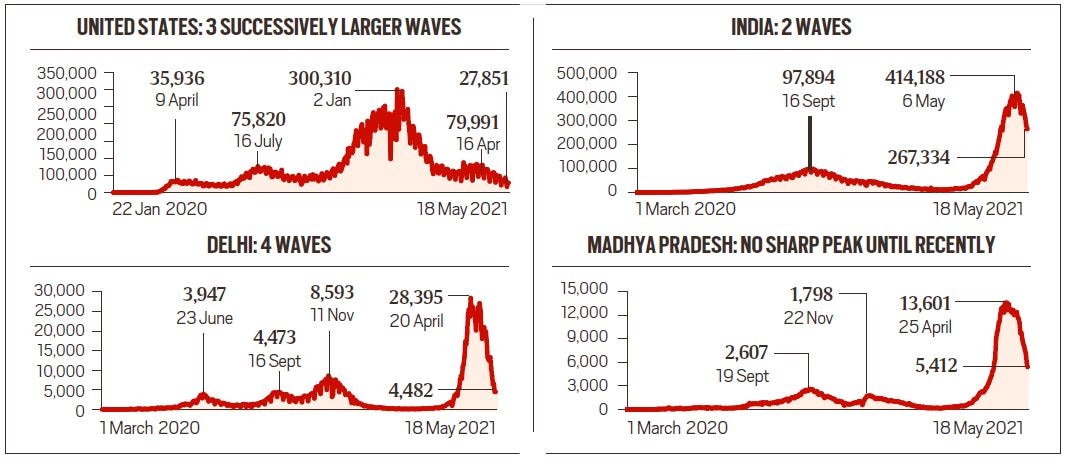

Covid-19 has continued relentlessly for the last one-and-a-half years, but in every geography, there have been periods of surge that have been followed by a relative lull. In India so far, there have been two very distinct periods of surge, separated by a prolonged lull.

Smaller regions within a country, a state or a city, for example, would have their own waves. Delhi, for example, has so far experienced four waves. There are three very distinct peaks in its growth curve even before the current wave, while in states like Rajasthan or Madhya Pradesh, the growth curves had a much more diffused look until February, lacking a sharp peak. It would be difficult to identify distinct waves in such a situation. (See graphs)

So, how would one identify a third wave, if it comes?

The third wave currently under discussion refers to a possible surge in cases at the national level. The national curve seems to have entered a declining phase now, after having peaked on May 6. In the last two weeks, the daily case count has dropped to about 2.6 lakh from the peak of 4.14 lakh, while the active cases have come down to 32.25 lakh, after touching a high of 37.45 lakh. If current trends continue, it is expected that by July, India would reach the same level of case counts as in February.

If there is a fresh surge after that, and continues for a few weeks or months, it would get classified as the third wave.

In the meanwhile, states could continue to experience local surges. Like it is happening in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh right now. Or, at a more local level, in the districts of Amravati, Sangli and a few others in Maharashtra. But as long as they are not powerful enough to change the direction of the national curve, they would not be described as the third wave. Also, the more localised the surge, the quicker it is likely to get over, although cities like Mumbai and Pune have gone through prolonged surges.

Will the third wave be stronger?

There has been some speculation about the third wave being even stronger than the second. However, this is not something that can be predicted. Usually, it is expected that every fresh wave would be weaker than the previous one. That is because the virus, when it emerges, has a relatively free run, considering that the entire population is susceptible. During its subsequent runs, there would be far lower number of susceptible people because some of them would have gained immunity.

This logic, however, has been turned on its head in India’s case. When the number of cases began declining in India after mid-September last year, only a very small fraction of the population had got infected. There was no reason for the disease spread to have slowed down, considering that such a large proportion of the population was still susceptible. The reasons for the five-month continuous decline in cases in India is still not very well understood.

And since the second wave was expected to be weaker than the first, many were fooled into believing that the pandemic was nearing its end. With the lessons learnt in a very painful manner, there are now suggestions that the third wave might be even stronger.

But that might not be the case. A far greater number of people have been infected during the second wave than the first. With the positivity rate almost four times that of the first wave, the unconfirmed infections — those who were never tested — is also expected to be large. In addition, vaccination would also induce immunity in a large proportion of the population. So, there would be a significantly lower number of susceptible people in the population after the second wave.

However, gene mutations in the virus can alter these calculations. The virus can mutate in ways that make it escape the immune responses developed in the already infected people, or those vaccinated.

But is it inevitable?

The third wave is a distinct possibility. It is likely to come, although the scale or timing is not something that can be predicted. But it is not inevitable. As mentioned, VijayRaghavan, the Principal Scientific Advisor, also modified his remarks, clarifying that it could possibly be avoided if people continue to take strong measures. It’s also possible that this time, the fresh wave will be indeed much smaller than the previous one, so that it inflicts much less pain and can be managed more efficiently.

A lot would depend on how people heed these warnings. They can become paranoid about an incoming disaster, or get numb to repeated warnings. The second wave has taught us that it is far better to remain paranoid and cautious than be hopeful in a situation like this.

Source: Read Full Article