A new virtual exhibition, 'Bagh-e-Hind', takes audiences through the fragrant worlds of Indian miniatures, one note at a time

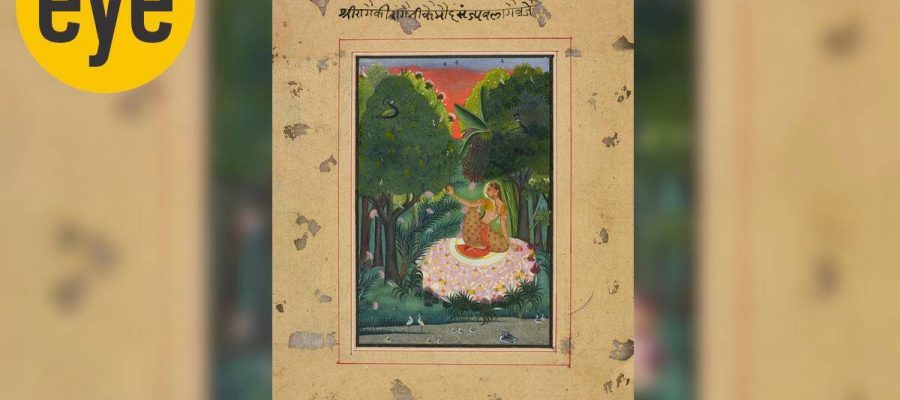

In a miniature painting from 18th century Rajasthan, now in the Smithsonian in Washington DC, a dressed-up Radha, seated on a bed of flowers in a clearing framed by a thick forest, waits for her lover Krishna. It’s twilight. Will Krishna turn up for this tryst? Or is he going to stand her up?

The painting is part of a ragamala (a set that illustrates Indian classical-music ragas) and conveys the pain of longing. Radha’s desire seems to be projected on the forest, set with blooming shrubs and birds in boughs. Instead of vague floral decorations, the artists of Kota went for detail and specificity — creamy frangipani and champaka, pink oleander, thick sheaths of a plantain, velvety celosia, and spiky flowers of the pandanus, called kewra in parts of India. We can see the fragrant forest, but what if we could smell it, too?

Pune-based independent perfumer Bharti Lalwani, 40, and, scholar in South Asian Studies, Nicolas Roth, 32, launched a virtual exhibition, “Bagh-e-Hind” (Baghehind.com), on September 10, letting viewers explore the lush worlds of Mughal and Rajput miniatures through scents and smells.

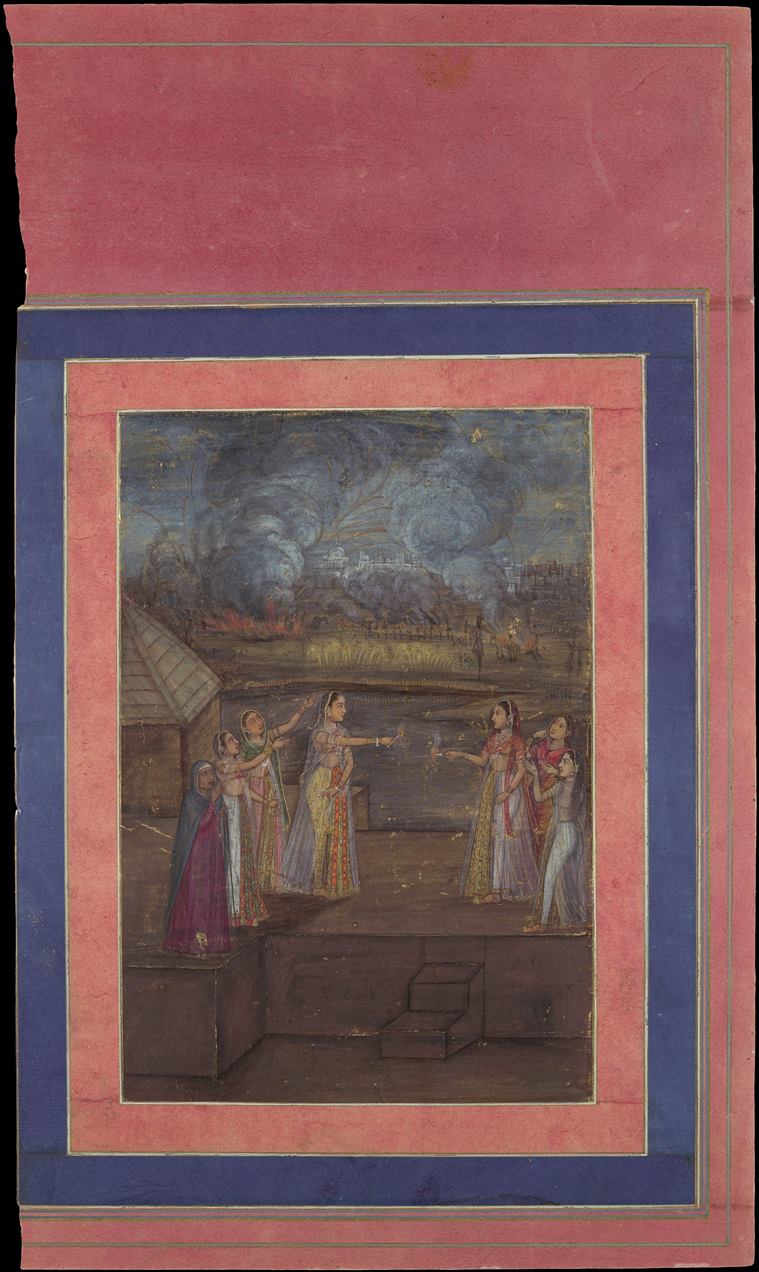

The idea was sparked off some years ago after Lalwani saw a 17th century painting of emperor Shah Jahan admiring jewels and ornaments with his son Dara Shikoh. The ornate frame around the scene was an explosion of flora and fauna, as elegant as the subjects of the painting, yet wild and uncontrollable. The King of the World could have his jewels but the natural world was beyond his purview, it seemed to Lalwani, who says, “These paintings communicate a lot of smell. Contemporaneous audiences would have known them — this idea of a summer garden, pleasure garden, abundance in nature — parrots digging into mangoes or bees drunk with honey.”

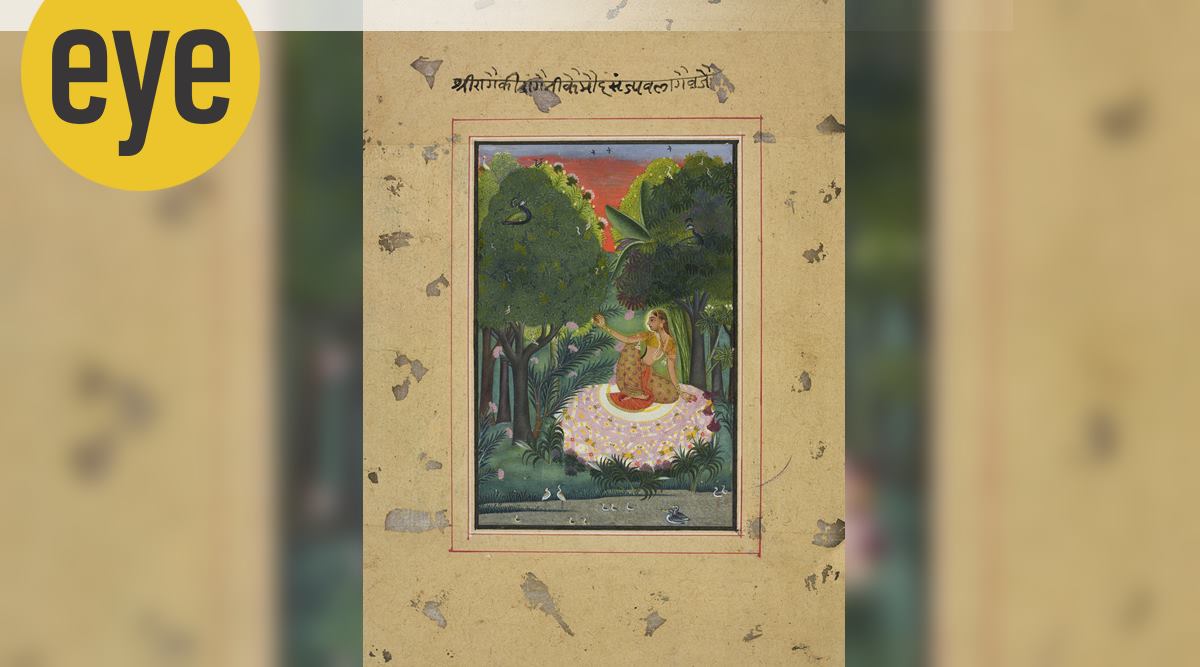

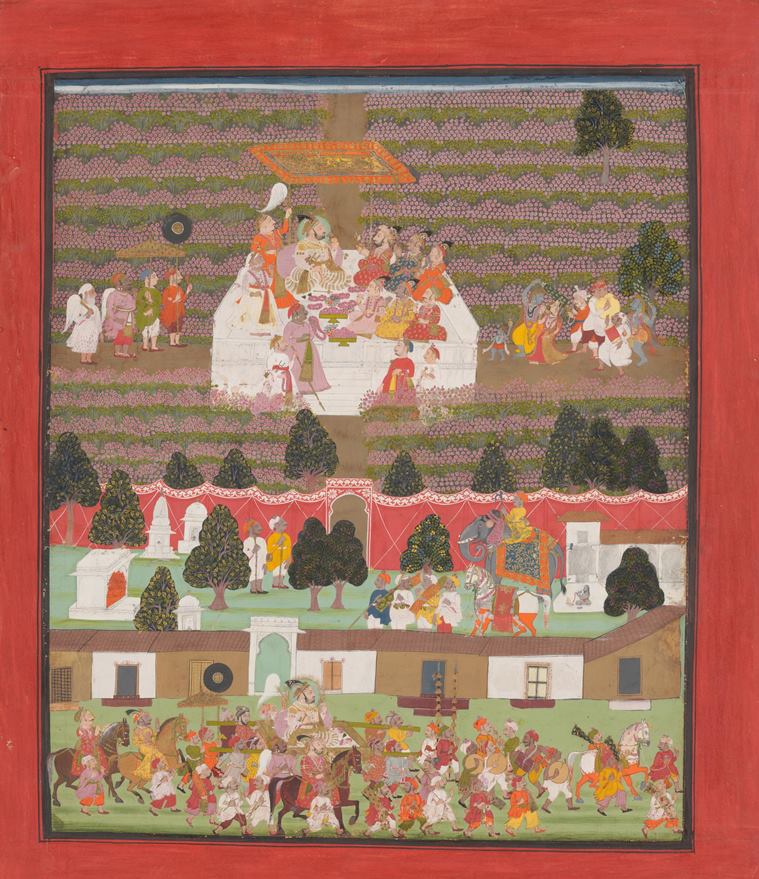

The curators categorise the exhibition into five sections, not all of them are flower-based. Rose (led by a gulab bari garden), iris, narcissus and kewra are themes here, but so is smoke (a fireworks display). It’s a layered idea of what the olfactory could mean in Indian paintings.

Roth, based out of Cambridge, the US, has a PhD from Harvard University on garden culture and horticultural writings of 16th-18th century Mughal India. He chose paintings with prominent olfactory elements as well as those representative of a particular genre convention. In the Narcissus section, for instance, the lead has two aristocratic young men sitting across each other on a garden terrace, sniffing sprigs of narcissus, with a bowl of, perhaps, jasmine between them. “The allusion to fragrance is clearly a pivotal aspect of the image, with the narcissi beautifully and naturalistically rendered. Narcissi are frequently referenced in Persian and Urdu poetry, where they commonly represent beautiful eyes and thus allude to vision and insight, but also to flirtatious glances and intoxication,” Roth says. Yet, this exceptional painting is an example of a large corpus of similar compositions — pairs of men or individuals, on garden terraces, surrounded by various accoutrements of the good life, as imagined by early modern South Asian elites, Roth adds.

Smell associations, more than sight, are known to be instant and instinctive. It’s the whiff of cake baking at our neighbour’s that reminds us of a grandmother who’s passed away; or the hint of cologne that reminds us of a former lover. They spark off emotions and nostalgia, like (novelist Marcel) Proust’s madeleine moments, and at the very least, there’s something primal and pheromonal about them. Given the vivid detailing in Indian miniature paintings, one may think that the olfactory aspect is therefore an obvious one. Yet, among the small number of scholars who study Indian miniatures, there’s hardly any research till date on this aspect.

It’s hard to confirm whether the original audiences of these paintings approached the works in the manner in which the exhibition encourages us to. Roth says he’s yet to find evidence of painters specifically trying to evoke olfactory experiences. But the wealth of detailed depictions of fragrant flowers, perfume bottles, incense burners and similar objects, and frequent and extensive references to scents and perfumery in contemporary literary texts strongly suggest this was something very intentional on the painters’ part, he adds.

It’s ironic that the exhibition has opened virtually during a pandemic, one in which we are desperately trying to protect our noses and mouths. In an attempt to overcome the current fate of humanity, the curators aim to tease our noses and taste buds by using language loaded with olfactory references, snatches of their conversations, poetry, historical objects associated with the paintings, and flowers from Roth’s personal garden. Also, sound design has been created by Berkeley-based landscape architect Uzair Siddiqui.

The highlight — at Rs 27,000 each — is Lalwani’s “synaesthesia box”, custom-made for each section. Lalwani, who’s been creating perfumes since 2018 under the label Litrahb Perfumery, put together attars and trademarked “edible perfumes” section-wise. These respond to the cues in the paintings, mixing and matching them with other notes. The Rose section’s edible perfume, for instance, translates a hot and sweaty summer in India using a dark chocolate spread created with vetiver, groundnuts and jaggery.

Much like South Asian art history, where some of the finest works were smuggled or looted out of their lands of origin, perfumery has a problematic history too. Lalwani explains how the raw materials used in perfumery are often exploitative in nature, such as natural civet musk, which is extracted after great pain to the animal. Furthermore, perfumers have often cast an Orientalist eye towards South Asia and Mughal gardens to seek inspiration for their products. Take Guerlain’s Shalimar, created in 1925, inspired by Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal’s love story. Their advertisement from a few years ago features a Russian model awaiting her lover, and the Taj Mahal sprouting out of a lake in Rajasthan. If the commerce of perfume and paintings is troublesome, Lalwani hopes “‘Bagh-e-Hind’, in contrast, offers a lot of beauty and a lot of stillness”.

The exhibition presupposes audiences’ familiarity with scents. So, if we’ve never seen or inhaled a narcissus, much is left to the imagination. And, it’s equally possible that our familiarity with some scents means the paintings evoke associations that are far removed from their original intent. Kewra, for instance, is used as cheap biryani flavouring today, unlike its historic use, as Roth discovered, when it was a coveted perfume ingredient. So, while the kewra intoxicates a Radha with longing for her missing date, it’s perfectly acceptable if audiences are reminded of the best, or worst, biryani or korma they ever had.

Source: Read Full Article