Thirty-four years after he traveled to space, Wing Commander Rakesh Sharma tells Rediff.com‘s Archana Masih that he looks forward to Gaganyan, India’s first manned space mission in 2022.

At the rather compact tea table where I am sitting opposite the first Indian in space, I realise we are bound by a kinship of broken ankles.

He had broken it in four places several years ago.

I had broken mine in three places five months ago.

Of course, the similarity ended right there. The circumstances of our accidents were as far apart as heaven and earth.

I fell on a hill trek. He broke his ankle after ejecting from a military aircraft he was test flying — so you know what I mean.

After exchanging notes on surgery and advice on physiotherapy, the mild mannered and soft-spoken retired Indian Air Force officer takes to matters pertaining to a national event four years from now that will be like nothing seen before.

That day in 2022 when Indians will travel to space aboard an Indian spaceship, making India only the fourth country — after the then Soviet Union (now Russia), the USA, China — to make the extraterrestrial journey.

Back in 2012, the former test pilot had written a paper about an Indian manned space mission and sent it to the Indian Space Research Organisation. Last year, five years later, his advisory note was acknowledged and he was called for an internal meeting.

Then this year, the prime minister announced India’s first manned space mission in his Independence Day address.

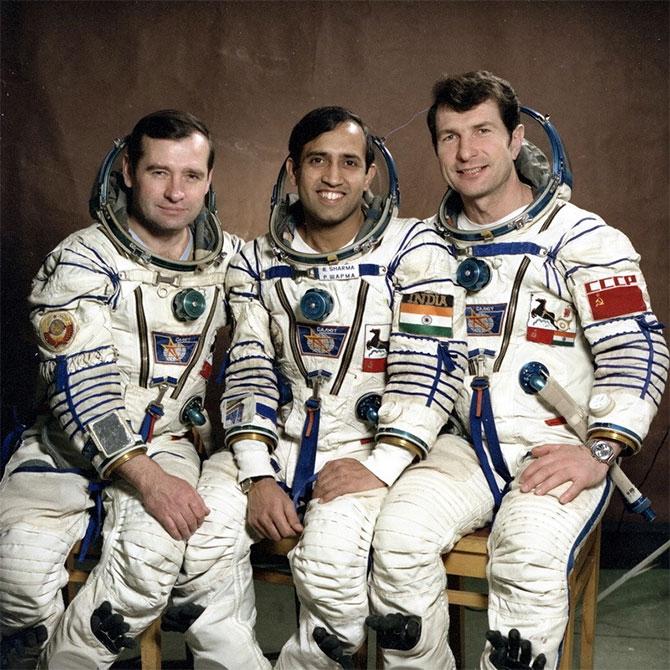

“It’s a good strategic move because then we win our spurs so to speak and become a full-fledged spacefaring nation. When future international treaties are forged about the utilisation of space, we will have a voice and that I think is important,” says the retired wing commander, now 70, who spent 8 days in 1984 aboard a Soviet space ship.

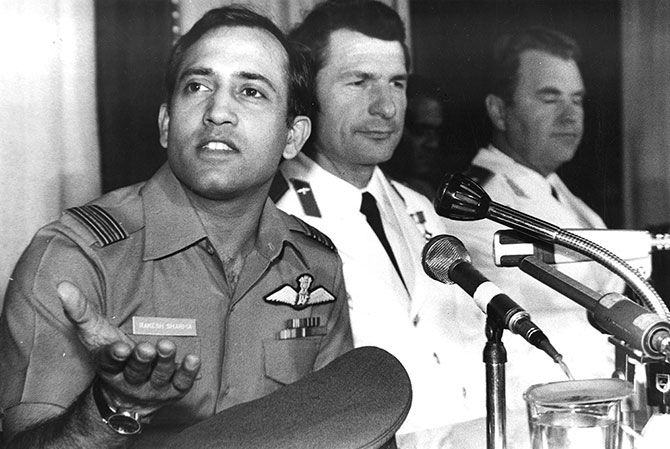

He was awarded the Ashok Chakra, the country’s highest gallantry honour in peacetime for the journey that captivated the nation and made him a national hero.

A film on his life is scheduled to be made. It was first to feature Aamir Khan, now reportedly Shah Rukh Khan will play the role.

The news about India’s manned space mission came as no surprise to Rakesh Sharma. He had long expected it.

“The pieces of the puzzle were already there, the whole mosaic hadn’t come together. We are pretty much there with our satellite programme and so it was the next logical step.”

“We have become a commercially viable launch agency for payloads and have in totality realised Vikram Sarabhai’s vision of leveraging space technology for socio-economic ends. Our country has derived direct benefit from it and the return on investment has been huge.”

A fighter pilot who trained for his space mission for 18 months, he feels the IAF pilots selected for the forthcoming space travel will obviously have to be at the top of their game.

“By virtue of their specialisation, test pilots really are most comfortable adapting to newer environments. That’s the reason why traditionally they have opened up the envelope, proven the system before it becomes business as usual,” says Wing Commander Sharma who spent many years as a test pilot after his return from space.

“Most spacecraft systems are often extensions of military aircraft systems so the tech environment is familiar to an extent.”

The IAF’s Bengaluru-based Institute of Aerospace Medicine will select the astronauts from a pool of nearly 30 pilots.

Four years seems an aggressive timeline for the Indian manned mission that includes the selection of pilots, their training and launch.

“The selection of our pilots shouldn’t take long. There are still four years. There is enough time for training,” says Wing Commander Sharma who was trained at Star City outside Moscow.

This month he will visit Russia to participate in an event to commemorate Indo-Russia cooperation.

The Soviets had honoured him with the Hero of Soviet Union title on his return to Earth and also gave him a key to a house which he did not get a chance to see then.

This time around he hopes to pop in and have a look around.

“It is different for NASA,” he points out, “for them it is an ongoing programme. They have to maintain a bench strength for astronauts,” he says.

“Here we are preparing for an event, not a process, which is not to say that the manned space programme will come to a halt. It has to be continuous; therefore the funding has to be continuous, irrespective of the government in power.”

“This is a national project which needs clarity of vision.”

Rakesh Sharma was a student when Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space and remembers lapping up every written word in Life magazine on the event.

The Indian mission will once again bring human space flight into Indian homes and fire the imagination of its youth. Very much like it did when he told then prime minister Indira Gandhi on live television that India looked ‘Saare Jahan Se Accha‘ from space.

Grand events have the potential to steer the course of nations and India can leverage it to great advantage, he feels.

“It’s like gaining expertise in cutting edge technology and using it as a soft power instrument for diplomatic outreach — like what ISRO has done for India.”

“In today’s conflict ridden world, it provides India a handle with which to do things differently and bring in cooperation to assist those lower down in the development ladder — not as the big brother but as a supportive elder having reached there before them.”

“We have the opportunity to influence other nations who are getting ready to colonise the Moon and Mars to try and get them to collaborate in this endeavour.”

“This is nothing original. The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs has clearly enunciated that space belongs to everybody, you need to have a voice of reason and ours can be that voice.”

Thirty-four years after his return from orbit, Wing Commander Sharma speaks like an ambassador for space. He advocates using it for the greater good of mankind, emphasising on “cooperation” among spacefaring nations rather than “competition”.

“If you want to reduce conflict on the planet then you have to reduce the divide. Almost every Indian PM on a cultural platform has spoken about Vasudeva Kutumbakam (the world is one family), make it happen in this way.”

“Make your earth resources software available to Bangladesh, Nepal — in fact, India has put up a SAARC satellite, but there are no buyers. People think they are going to be counted as India’s vassals — some aggressive marketing needs to be done that we are not big brothers.”

“This is one way of assuring peace in our region and would be a concept for the rest of the world.”

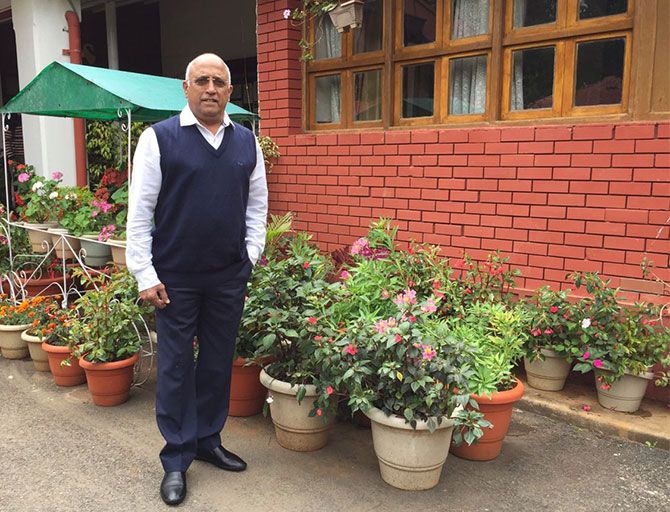

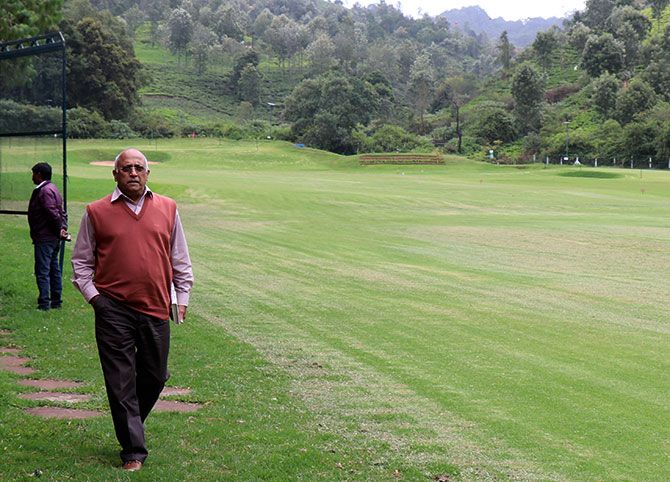

On a quiet, sunny morning at the Wellington Gymkhana Club in the Nilgiris where we are meeting, the space traveler and former Mig-21 pilot had recently returned after tending to his sick daughter in Mumbai.

A club executive committee member politely interrupts our conversation for some information needed before the dinner with the visiting British high commissioner that evening. Wing Commander Sharma promises to find out and Whatsapp the information.

Nilgiri tea is ordered with some biscuits. Overlooking a lush green golf course and tea gardens, it is a magical location for a cup of tea.

In a largely poor country, aspiring to lift her people out of poverty, is a manned space programme an exercise in space vanity, I ask?

“Of course not. No. No,” he laughs. A man reluctant about his celebrity, he prefers keeping a low profile which is one of the reasons he settled down in the quiet hills.

“Today our country is running the cheapest and most effective space programme in the world, acknowledged by other space powers.”

“It is giving us valuable inputs for our economy and has connected every corner of the country. I daresay it has compressed our development time slot.”

“The way technology is galloping, you’ve got to sprint today to stay at the same place. We cannot do these things sequentially and play catch up.”

“You can’t say first we are going to eradicate poverty and then think of space. You’ve got to find a way to move and not be left behind.”

Wing Commander Sharma speaks about the collaboration with France and Russia in this endeavour and says it is the right way forward till our own infrastructure comes to speed.

ISRO Chairman Dr Sivan K has said the space mission — Gaganyan — will not only be ISRO-specific but include several other institutions and individuals.

“It’s going to be a humongous project management challenge requiring outstanding leadership,” says Wing Commander Sharma.

ISRO hasn’t reached out to him yet, but if asked for any input, he would be happy to help.

“It is incredible that ISRO has been doing this with whatever meager funding it gets compared to other space nations. I just hope it is not going to go the same way as the (Hindustan Aeronautics Limited-made) Light Combat Aircraft Tejas which also needed a lot of synergy.”

The indigenously built multi-role fighter jet has been under development by HAL for over three decades and crippled with delays. It was started around the same time Wing Commander Sharma went to space.

“It’s a great opportunity to show we are up there. The biggest pitfall potentially would be if ISRO approaches a manned space programme as just another mission where a human being is riding on top, instead of a satellite.”

“When you are doing something new, things are different and you need the expertise of those who have been doing something new all the time.”

Looking back at his time when he ventured into space riding on somebody else’s technology in a Cold War-ridden bi-polar world, Rakesh Sharma now looks forward to see Indian astronauts go up on ISRO’s launchers.

“ISRO has earned quite a reputation of having all first attempts successful — Chandrayan, Mangalyan and now Gaganyan — touch wood!”

“All we want is a successful safe return.”

Source: Read Full Article