Gandhi never visited Rashtrapati Bhavan as it is now, but his visits to the viceroys who once lived there were like encounters between the might of an empire and the moral force of a nation.

Written by Praveen Siddharth

One of the popular exhibits in the Rashtrapati Bhavan Museum is an interactive experience called ‘Walk with the Mahatma’. Visitors see themselves projected on a screen walking alongside Mahatma Gandhi across the forecourt of the Rashtrapati Bhavan. It is an instant favourite with those who delight at the experience of feeling part of history.

But did the Mahatma really visit Rashtrapati Bhavan? This question led me to pore over some old records. Technically, of course, he did not, since this magnificent building became the Rashtrapati Bhavan only in the 1950s. Before that it was the ‘Viceroy House’ and ‘Government House’. If we leave the semantics aside though, things become interesting. Construction of the Viceroy House began in 1912 and was complete only by 1929. Lord Irwin became its first resident sometime in February 1931 and one of the early visitors to the Viceroy House was, in fact, Mahatma Gandhi. On February 17, 1931, he held the first of his famous meetings with Lord Irwin. Having just been jailed for the Dandi March and Salt Satyagraha, he is famously said to have carried his own salt in a packet and used it to mix in his nimbu pani.

Gandhi met Irwin eight times until March 5, 1931, leading ultimately to the Gandhi-Irwin pact. Images of the modestly-clad Gandhi at the grand new Viceroy House rankled several important people in London. Winston Churchill, during an address to the Council of the West Essex Unionist Association on February 23, 1931, lamented, “It is alarming and also nauseating to see Mr Gandhi, an Inner Temple lawyer, now become a seditious fakir of a type well known in the East, striding half-naked up the steps of the Viceregal Palace, while he is still organising and conducting a defiant campaign of civil disobedience, to parley on equal terms with the representative of the King-Emperor.”

Ironically, today, just outside the walls of the Rashtrapati Bhavan, the salt march is immortalised in bronze in a sculpture popularly known as Gyarah Murti by the eminent sculptor Devi Prasad Roy Choudhary (1899-1975). The other prominent visit of Gandhi occurred on October 12, 1939. World War II had broken out. Along with Rajendra Prasad and Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Gandhi met the viceroy Lord Linlithgow about the Indian participation in the British war effort. The meeting wasn’t successful and Linlithgow in a statement on October 17 refused to commit to the demands for independence in return for India’s support in the war. Commenting on this episode, Gandhi remarked, “We had gone to ask for bread and instead got a stone.”

The launch of the Quit India movement in 1942 led to Gandhi being jailed in Pune at the Aga Khan Palace between 1942 and 1944. Meanwhile, on October 20, 1943, Linlithgow left India and Lord Wavell became the new viceroy. Writing in his journal, Wavell records that that everyone in London commented that he was lucky compared to his predecessors. The biggest decision they had to face was “whether and when to lock up Gandhi,” whereas Wavell would find him already locked up. The issue that would actually worry Wavell was the spectre of famine over India. In this grim scenario, the former American President Herbert Hoover visited India on April 24, 1946, to discuss American aid to tide over the crisis. Wavell invited the nationalist leaders to the Viceroy House to meet Hoover. Gandhi and Nehru accepted, but not Jinnah.

After the meeting, in a statement to the press on April 26, Gandhi said, “Mr Hoover’s flying visit to India has excited considerable interest and possibly hope. Whilst all the help that America and other countries can send to India, struggling against starvation, must be welcome, my endeavour has been to find ways and means to make ourselves self-supporting… nature never fails those who will help themselves.” Words that would find resonance today as we aim to build an “atmanirbhar Bharat”.

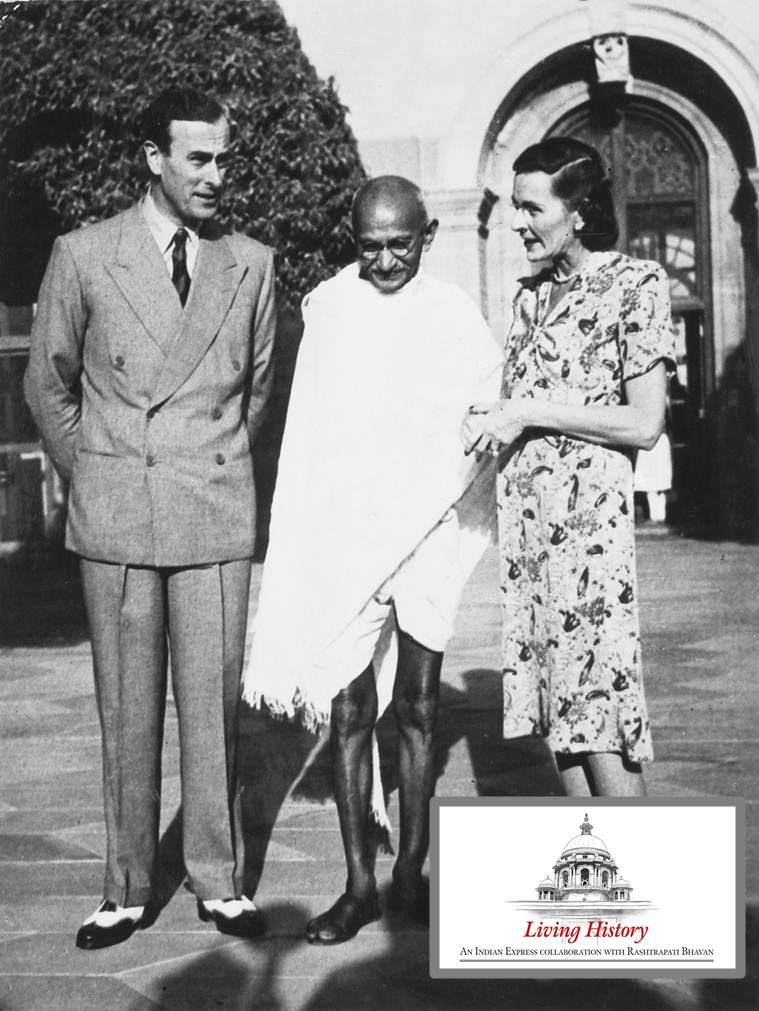

One of the more popular images of Mahatma Gandhi at the Rashtrapati Bhavan is, perhaps, of his meetings with the viceroy Lord Mountbatten in April 1947. Gandhi met him on April 1, 2 and 3, for discussions on the composition of the interim government. An aide of Mountbatten noted that during one of these meetings Gandhi “stayed on for afternoon tea, which was arranged on the lawn and did not touch either the cakes or the sandwiches, but chose to eat a bowl of goat’s curd which he had brought with him.”

On June 2, 1947, Mountbatten again invited Gandhi and other national leaders to the Viceroy House to win their support for his plan for Partition. Gandhi’s support was considered the most crucial. Mountbatten feared that his plan stood no chance if Gandhi spoke publicly against it. As Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins recount in their book Freedom at Midnight (1975), what followed was certainly the most bizarre visit. June 2 happened to be a Monday — the day of the week when Gandhi observed a vow of silence. After listening to the earnest persuasions of Mountbatten, he scrawled a cryptic note on the back of a used envelope, “I am sorry I can’t speak. When I took the decision about the Monday silence, I did reserve two exceptions, i.e. about speaking to high functionaries on urgent matters or attending upon sick people. But I know you don’t want me to break my silence…if we meet again, I shall speak.” The next day Mountbatten announced the Partition of India, over radio, after obtaining the consent of Jinnah and Nehru.

Gandhi’s untimely death in 1948 meant that he never visited the Rashtrapati Bhavan to meet an Indian president. However, fate provided a short and beautiful window of opportunity. In November 1947, Mountbatten left for England to attend the royal wedding of his nephew Philip with Princess Elizabeth, elder daughter of King George VI. C Rajagopalachari was announced as the acting Governor-General and he moved in temporarily to the Government House, which the Viceroy House had now come to be called. Gandhi visited him on November 20, and, for the first time in history, he saw an Indian reside in the building. The visit was even sweeter since Gandhi and Rajaji had become co-fathers-in-law by then.

In retrospect, Gandhi’s visits to the Rashtrapati Bhavan were never really just visits. Rather, they were encounters between an empire, symbolised through a colossal structure, and the moral force of a nation embodied in one scrawny and frail man. These encounters, slowly but surely, tilted the balance of power and chipped at the foundations of the British colonial rule. At the same time, the encounters also changed the character of the Rashtrapati Bhavan itself. From being a sign of British domination, it became a structure epitomising our unity and national spirit.

Decades before any of these encounters took place, educator and missionary CF Andrews wrote on February 21, 1924, “There is a ruler of India here, Mahatma Gandhi, whose sway is greater than all imperial power. His name will be remembered and sung by all the village people long after the names of the modern governors in their palaces in New Delhi are forgotten…for there is a spiritual palace which Mahatma Gandhi built out of an eternal fabric. Its foundations are deeply and truly laid in the kingdom of God.” No words have proved to be more prophetic.

Praveen Siddharth is private secretary to the President of India

? The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Eye News, download Indian Express App.

Source: Read Full Article