Arundhuti Dasgupta maps a trail from the southernmost tip to its suburbs.

At first brush, Mumbai is a brusque city. There is no lingering over monuments as one would do in, say, Delhi or Kolkata.

Nor is there a strong, singular cultural footprint that can guide new initiates and experience-seeking tourists through the city.

But dig past the indifference and the city crackles to life, revealing a fine mesh of stories, symbols and belief systems, all influenced by the many cultures that inhabit it, as also a pastiche of folk goddesses.

The city’s patron deity is Mumba Devi. Her temple is in a crowded alleyway in Pydhonie, south Mumbai — the name is because there used to be a creek nearby that people could wash their feet in.

This wasn’t her home to start with, but the records are typically vague about where the goddess moved house from.

Some say the first temple was close to the present-day Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus (formerly Victoria Terminus), but others insist it was further south.

She moved home because her worshippers, a migrant community of workers from Gujarat and other regions, adopted her as their own and, much like the city’s harried commuters today, were merely looking to cut some travel time for their daily temple run.

Today Mumba Devi is believed to be an avatar of Parvati, wife of Shiva, but her origins lie in the folk traditions.

Some trace her back to Munga Devi, one of the seven guardian goddesses of the Kolis.

Some say she vanquished a giant, Mumbaraka, a demonised version of one of the city’s earliest Mughal invaders, Mubarak Shah.

Yet another version has her as a migrant, moving to the city with a group of nomadic traders from Gujarat who claimed to have descended from Ravana (Mumbadevi and The Other Mother Goddesses in Mumbai, Marika Vicziany and Jayant Bapat).

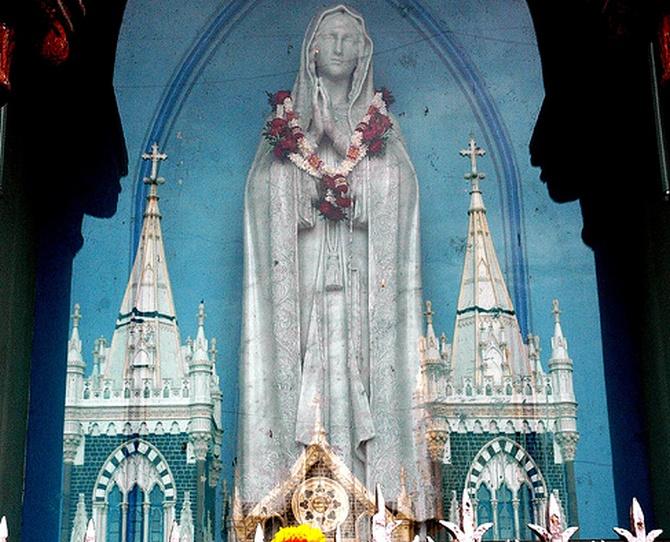

Mary of Mumbai

• Christianity and Hinduism have lived cheek by jowl in the city for centuries. The Kolis believe Mary to be one of the seven original goddesses of the city. Every year, she and her sisters bless the city and invite its people over for a feast together at the annual festival at Bandra.

• Strewn across are churches dedicated to Mother Mary of Velankanni, a saree-clad figure who takes her name from a village in Tamil Nadu. She too has an annual pilgrimage-yatra (much like the folk goddesses in the city) where devotees throng her churches in huge numbers.

Her folk roots are also evident from the form she is worshipped in: an elaborately painted stone that is believed to have emerged from the sea.

A village goddess is mostly represented only as a head (a stone painted with a vermillion paste), because the village is her body and has been created from her flesh and blood.

Village or folk goddesses are also always found close to the boundaries of a region, because as protectors, they are ever watchful of those entering and leaving their precinct.

And Mumbai has many such. In fact, the modern city as we know it today owes its genesis to a dream about three goddesses.

A government contractor, Ramji Shivaji, dreamt that goddesses Mahalaxmi, Mahakali and Mahasaraswati were unhappy because they had had to flee their original haunts in Worli and hide in the creek after Mubarak Shah’s men captured Bombay in 1318.

Shivaji’s dream came in handy for William Hornby, the governor of the city in the early 1770s, who was struggling to build a wall that would dam the creek and close the breach between the islands of the city.

Shivaji, urged by the goddesses in his dream, cast a net into the creek and pulled them out. An embankment was built soon after.

A Mahalakshmi temple now marks the spot inside a narrow lane off Bhulabhai Desai Road, some 6 km from the Mumba Devi temple.

Interestingly, the story about a giant-demon-Mughal ruler forcing goddesses into hiding is repeated in several parts of the city.

It makes its way down the road from the Mahalakshmi temple to one dedicated to Prabha Devi, whose name also marks the area.

She, along with her sisters (Kalika Devi and Chandika Devi), jumped into the Mahim creek to escape the sultan, goes the story.

None of the stories mentions the goddesses being terrorised by the British, however, though they too were an invading force — probably because they were the ones recording the stories.

Close to the Prabha Devi temple is a cluster of folk-village deities. Not all have temples in their name though.

For instance, there is Khokhla Devi who is believed to cure whooping cough and TB.

She lives within a large temple dedicated to Shiva and is a recent goddess, said to have come up around mid-1800, a time when the city was going through repeated cycles of infectious diseases.

Another goddess in the area is Golfa Devi. Her temple is on the Worli-Koliwada stretch, just a step down from the busy Bandra-Worli Sea Link that connects the western suburbs to South Mumbai.

It is among the oldest settlements of the city’s fishing community, the Kolis, who worship Golfa Devi.

Along with her sisters, Sakba and Harba Devi, she is much sought after for her predictive abilities.

Known as the “yes-no” goddess, her worshippers seek her counsel for a string of issues: Will I pass this exam? Should I take my boat out into the sea? She answers by dropping one of the two silver balls placed on her shoulder: if the right one drops, it’s a yes.

The priests who attend to her needs say that there is a never-ending stream of people and questions every day.

And every year in January, devotees throng the narrow lanes that lead up to her temple for an annual procession.

The goddesses of Mumbai often serve routine, domestic functions. They cure diseases, absorb people’s sorrows and even help one sleep at night.

Their temples are mostly egalitarian places of worship. Most are also cosmopolitan, often sharing temple space with diverse forms of faith.

For instance, in a small lane off Mahim, a messy and chaotic neighbourhood that is predominantly inhabited by the city’s Muslim and Christian community, is a temple dedicated to both Sitala Devi and Mariamman.

The two are goddesses of migrants. Sitala is worshipped mostly in the east and the north of the country, while Mariamman is a Tamil folk goddess.

Sitala was born out of the ashes of a yagna fire and can cure, as well as cause, small pox.

She carries a pot in one hand and a broom in another, the pot holding the source of the disease and the broom meant to sweep it away.

Mariamman has many stories attached to her origin, the most popular being that she self-immolates upon discovering that she has been cheated in marriage and wreaks havoc upon the village that turned her into an outcast.

The two live harmoniously inside the same temple as do many temples, churches and dargahs in their vicinity. In a multi-faith city, its goddesses know faith trumps religion every time.

Source: Read Full Article