We got the same Diwali bonuses. We ate together. We carried equipment together on shoots.

And when the odd reporter tried to throw her weight around and leave the camera person to carry bags of equipment, cables, the camera and tripod down the stairs and to the shoot location, Prannoy would step in, take the tripod off the shoulders of the colleague silently, lightening the load, recalls Revati Laul.

Around the time NDTV broadcast its iconic programme — The World This Week, there was a music video by the rock band R.E.M.

It was for their Grammy winning song — Losing My Religion.

The video depicted strange winged men contrasted with dark Soviet film-maker Tarkovsky style pictures of religion and the Anti-Christ.

‘That’s me in the corner,’ said the lead singer — Michael Stipe. ‘That’s me in the spotlight, losing my religion.’

Many of us are in that corner, staring at the chasm NDTV leaves behind.

As I wrote a sentimental post about it on Facebook, I got a phone call from Kamal Kantji, who used to be a driver at NDTV.

He was overcome and wanted to talk about the old days. That’s what losing NDTV in its present shape and form means.

It’s the end of an egalitarian media space, where Kamal Kantji and I, anchors, reporters, camera assistants and the women who cleaned the toilets were all colleagues.

We got the same Diwali bonuses. We ate together. We carried equipment together on shoots.

And when the odd reporter tried to throw her weight around and leave the camera person to carry bags of equipment, cables, the camera and tripod down the stairs and to the shoot location, Prannoy would step in, take the tripod off the shoulders of the colleague silently, lightening the load.

At work, each of us built a lifetime of stories and experiences we carry every place we go. “Do you remember the time XYZ buzzed the Roys home #7 instead of #67 for kitchen at 2am, asking for tea?” And “Do you remember the time XYX walked out of the studio mid-discussion because they were uncomfortable with XXX?”

I remember starting my career as a production assistant on our breakfast show, Good Morning India and turning up for a shoot with no tapes to record on.

I remember getting stuck in the lift as the electricity went off and having to climb over the 7th floor roof to get back in to the office.

I have stories of riding the back of a buffalo to try and do an interesting piece to camera.

Of asking the sarpanch in a village in Gujarat about how much milk he gave instead of his cattle…because of my appalling Hindi.

I have stories of my sari pleats coming undone on the dance floor of our NDTV annual party.

Of going out for a few drinks before returning to office to do an edit before the Musharraf-Vajpayee summit and getting it done just in the nick of time.

Of going to report from Kargil and making everyone who didn’t get to go jealous.

Of being taken on a very short camel ride after a shoot at a Harappan excavation site — Rakhigarhi, where the villagers were too scared to allow the camel to ride farther, because of my colossal weight.

Of climbing over the wall of a nightmarish asylum in Indore and tracking the same story of its inmates over eight years.

We are a sub-species, us NDTVians. We write staccato, from writing to pictures.

We put three dots between every phrase because that’s how we marked our phrases to read them out in a voice over booth.

We talk rubbish when we meet and drink too much. We don’t know how to negotiate normal days.

We’ve become adrenaline junkies and we love chaos. We may have thrown daggers at each other in the newsroom but now, years later, even if it’s been ten or twenty years since we last met or spoke, it feels like yesterday.

That camaraderie isn’t palpable at other TV channels because the Roys made it this way and oh so subtly made us this way — people who did things together.

NDTV went through many avatars. I saw it phase out of being a production company making programmes for the State-run Doordarshan to producing the news for Star TV to then becoming its own set of TV channels.

There was a time when a large scant haired man with an overflowing belly — the Doordarshan censor would come review the tapes of our breakfast show before they went on air to make sure we hadn’t inserted film songs with kissing scenes in them. And then there was the time when we found out what it was like to ‘GO LIVE’ and we weren’t used to it.

So an entire bulletin went on air with the wrong sound mixed down and the director’s instructions in the studio ‘Cut to effing camera 6 now, effing tape IN’ as the primary audio. Audiences were treated to an expletive-ridden bulletin.

There was the eventual transition to the NDTV channels and a board and shareholders. And I remember wondering if this would mean the market eventually dictating content and editorial bowing down to money.

On one occasion when I was the channel’s reporter in Gujarat, the marketing person for the region asked me to soften a story because one of the people implicated was running the network’s cable television in that zone.

“You will never ever talk to me about anything like that again, am I clear?” I said to him.

From a distance and as someone who was on the inside, I could see how much of a struggle it was becoming over time, for a channel like NDTV to always put content first.

To have to do the trapeze act of not giving in to pressure from one establishment or another and yet keep the money coming in.

If NDTV was unsparing in its coverage of the Gujarat anti-Muslim pogrom, it was also unsparing of the coal and telecom scams under the Congress-led UPA regime.

With time, some of us could see the balancing of an absolute slayer like Ravish with advertorials for various state governments and the hiring of anchors that ‘played it safe.’

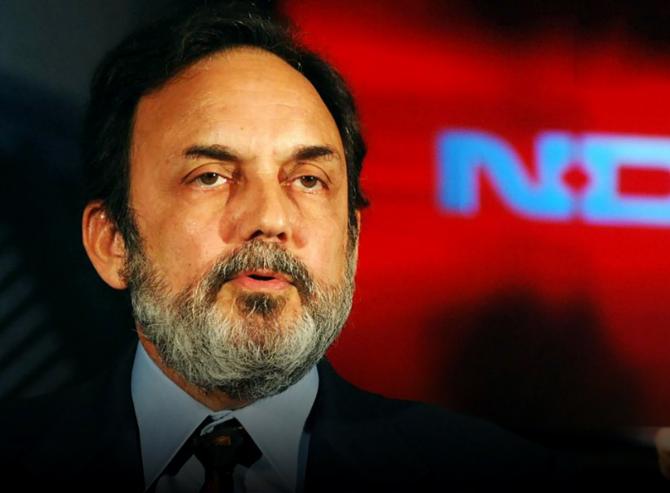

But only a Prannoy could pull off a heist like taking a camera in to a Vajpayee-Musharraf peace summit press conference and play it out for the country to see the farce that such press conferences had become.

Only a Prannoy could make the telling and re-telling of the caste arithmetic at play in election after election fun to watch.

Who’s going to sit across a studio desk with witticisms and repartee about his age in-between delivering a polite body-blow to a political hopeful? None of us at least can imagine turning on the TV after an election and not finding Prannoy and Dorab Sopariwala on it.

No matter what the order of the day, we had our stories — not on screen alone, off it.

We were the story — all of us, together. We were one continuously running movie and each of us owned our part.

“You know so and so deleted an entire show, again?” I said it was a bug, I didn’t want them to get into trouble yaar.

“You know the stories of the ghosts that walked the edit floors at night? XYZ got slapped once. And I felt I was being watched even though I was the only person on the news floor. It happened thrice. Then my b***s froze and I ran out, past the guard and came back up only two hours later when the producer turned up.”

“Yaar, XXX dislocated her knee while we were in the middle of rolling a bulletin. I called a surgeon in the ad break and he came and fixed it while the rest of us rolled the show.”

“The shift engineer sitting on my right kept digging his nose and rolling it into soft spherical balls and then to my horror, as we were rolling the programme, he came up to me, yanked the earphones out of my ear, saying they weren’t appropriate and then replaced them, with those same hands.”

Our stories cover the spectrum, but when we’re sprawled out on each other’s drawing room floors, we try and remember the most depraved, the most explicit of them all.

Like siblings with the same idiot parents, we mumble the same gibberish that only we find funny and can often complete each other’s anecdotes.

Looking back at those fuzzy, silly days from today’s time of precision-point clever, craven coverage replacing reportage makes that time feel unreal. Something I’ve conjured up to entertain you, the reader.

‘That was just a dream… that’s me in the corner…’ goes the R.E.M. song.

It’s hard to imagine what will come next. Who is going to give us the margin and swing votes peppered with Prannoy-isms about his age and the customary dig at fellow panelists Dorab Sopariwala and Shekhar Gupta?

For me, it’s like waking up to find I’m allergic to milk and I now have to find a powdery plant substitute and my coffee tastes like soap.

For those who feel NDTV ‘had it coming.’ It delivered one-sided news, I have this to say. What side would you like to be on in Putin’s Russia or Khamenei’s Iran or Erdogan’s Turkey? The thing about objectivity is that it’s a poorly understood concept and used by those who want to stamp out dissent.

They would like to have news be put on a weighing scale — apples on one side, oranges on the other — fifty each.

Well, there’s only one side left now. The gatekeepers can keep their brave new world.

The R.E.M. video is therefore a great metaphor for the end of NDTV as we know it.

As the lead singer gesticulates, strange images of winged creatures flapping haplessly are intercut with darkness and laughter that wears an artifice and a hand reaches out from one end of the screen terrifying the man and winged angel below. What’s coming next?

The song continues with the following line:

‘Oh no I’ve said too much… haven’t said enough.’

Revati Laul is a journalist and rights activist who started her career at NDTV in 1996 and worked there in three separate stints until 2009.

She subsequently switched to print, writing for Tehelka, The Hindustan Times, The Wire, The Quint.

She is the author of the book, The Anatomy of Hate.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article