It does not afford protection to refugees but, rather, it is a legal instrument to deny asylum and protection even to its intended beneficiaries were they to cross over to India today or tomorrow.

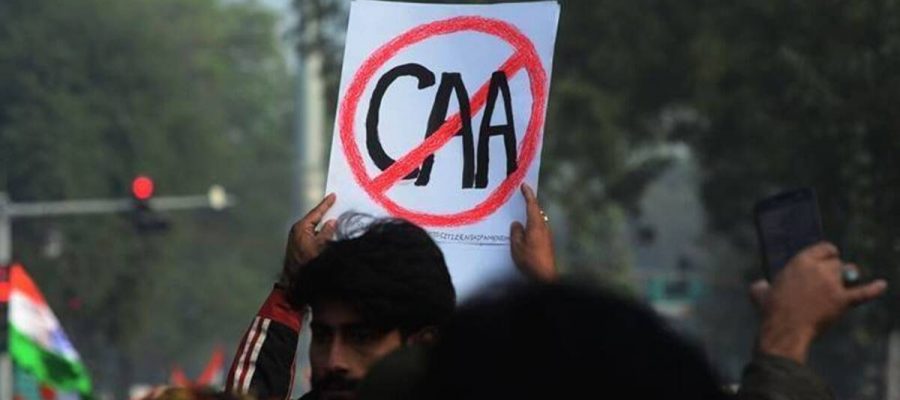

BJP President J P Nadda was joined by Union cabinet minister, Hardeep Singh Puri, in showering praise on the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019. The occasion was the evacuation of stranded Indians in Afghanistan against the backdrop of the Taliban’s ascendance to power in Kabul. With the help of the American forces stationed at the Kabul airport, the government of India could successfully evacuate a good number of its nationals. No less important was the evacuation of some Afghan nationals from the Hindu and Sikh minority communities in that country. Unfortunately, we see motivated propaganda to claim how their evacuation attests to the justification for the CAA. There is no way that these people would be given Indian nationality under the CAA. After all, the provisions of the Act are meant for those who have been in India since before December 2014. The CAA was never meant to help asylum seekers and protect persecuted people. Moreover, the government has been unable to frame rules for the implementation of the much-touted CAA despite the passage of 20 months. Also, there is absolute silence on the constitutionality of the CAA from our judiciary.

In the absence of refugee-specific legislation, the reception, admittance and treatment of refugees in India is conditioned by ad hoc policies adopted by the government to deal with specific circumstances. Thus, among several communities, we have hosted Tibetans, Tamil refugees from Sri Lanka, persecuted Chin and Afghan refugees and the minority Chakmas from the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). India had received worldwide admiration for its singular support to the huge numbers of people fleeing violence and persecution from then East Pakistan in 1970-71. The decision to amend the Citizenship Act, 1955, was initially thought by unsuspecting people to be benevolent. It was supposed to be the right step, consistent with broad Indian traditions and practices to stand up for persecuted people. However, it was made clear by the government that it does not propose any changes that are consistent with the understanding and interpretation of the term “persecution”. Rather, a discrimination-filled and narrow interpretation of persecution has found its way into a legislative Act, in direct contravention of the provisions on equality in the Indian Constitution.

The government also claimed that the CAA is about conferring citizenship. It does not intend to take away citizenship from Indian nationals. However, it would be difficult to find a precedent for a national legislative measure attempting to accord sanctuary and protection to a class of people retrospectively. A policy for persecuted people from foreign countries is invariably for the intended beneficiaries who need protection. Under the CAA, no one is eligible to be accorded protection unless they are already here in the country. For example, a group of Hindus from Bangladesh or Christians from Pakistan or Sikhs from Afghanistan would not get any protection from the CAA should they reach India and seek its protection. The question of refuge and protection for persecuted minorities, such as the Rohingyas from Myanmar or the Hazaras from Afghanistan, or asylum seekers from different other countries on the ground of “well-founded fear of persecution” does not arise at all. In short, the protection of persecuted minorities even from any of the three named countries in the CAA is not permissible. In consequence, the CAA does not afford protection to refugees but, rather, it is a legal instrument to deny asylum and protection even to its intended beneficiaries — the six named minority communities from three named countries were they to cross over to India today or tomorrow.

This does not mean that the absence of a legislative framework denies protection to asylum seekers. They may very well be the beneficiaries of such protection. They may receive asylum and, subject to the fulfillment of certain conditions, may be conferred citizenship in due course by the government. The government has all the power in this respect in its capacity as the executive authority of a sovereign state. This power with the government, however, is not born out of the CAA but has been its prerogative since the inauguration of constitutional democracy in India. This is exactly what the government can do and a step in this direction would be to grant visas to Afghan nationals for an extended stay in the country — for all those who have been living in the country for the past many years as well as for the few hundred Hindu and Sikh minority nationals who have just arrived.

The writer is professor of international relations, Jadavpur University; and TMC spokesperson

Source: Read Full Article