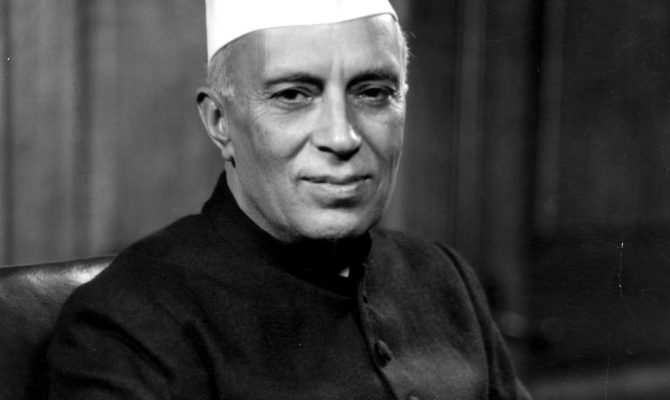

‘India’s first and longest-serving prime minister created — or at the very least imagined — a modern, democratic nation-State of the 20th century,’ says Sunil Sethi.

Despite a deliberate downgrading of his image and devaluing of his legacy there are good reasons to remember Jawaharlal Nehru.

India’s first and longest-serving prime minister (1947-1964) created — or at the very least imagined — a modern, democratic nation-State of the 20th century.

The words ‘secular’ and ‘socialist’ prefixed to the ideals of a republic are among the most contested and derided today, but they were the foundational underpinning of his beliefs.

But imagine it otherwise. Where Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi gives us a 600 foot high Statue of Unity costing nearly Rs 30 billion — as if height and expense are sole criteria in defining the tallest leader — Nehru gifted the city of Chandigarh designed by a leading international architect.

Where cleaning up the Ganga remains a half-realised pipe dream he penned, in a flight of romantic idealism perhaps, some of the most evocative lines in prose to India’s holiest river.

The late civil servant Badruddin Tyabji, credited with the inspired choice of placing the Ashoka Chakra at the centre of the national flag, is not the only one to recall in his memoirs that when his home in New Delhi was being looted during the cataclysm of post-Partition riots, an exhausted Nehru, in the midst of calming a city in crisis, appeared unannounced and to inspect the damage, expressed his personal regret, and ordered safety measures.

It is unimaginable that attacks on minorities would continue, or grow as some reports suggest, under his leadership.

It is unthinkable, if he was around, that a concert by Carnatic vocalist T M Krishna would be peremptorily cancelled by the Airports Authority of India pulling out as sponsors, as happened in the capital last year.

As the historian Ramachandra Guha pointed out: It may be ‘intolerant’ when his appointment to a chair at Ahmedabad University is withdrawn after Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad portraying him as ‘anti-national’ and ‘separatist’ but to hound Mr Krishna as an ‘urban Naxal’ and ‘converted bigot’ is nothing less than ‘barbaric’.

Nehru ruled by consensus, not by whispered diktat or via armies of vicious trolls.

He respected the political Opposition and was accessible to a questioning media, viewing criticism as a necessary, not hostile, form of public debate.

He faced head on, the wrath of an array of ideological opponents, from the Socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia to the right-wing cow-venerating industrial baron Ramkrishna Dalmia.

They, together with peasant leaders such as Chaudhary Charan Singh, attacked him on a range of policy and personality issues — from land reform and taxation to free enterprise and his upper class, Anglophone, Brahmin antecedents.

There may not be many Nehruvians around, including in his own party, but there is often sound reasoning in critiques of Nehru.

Inadvertently or not, he subtly promoted dynastic succession. He made serious policy mistakes, neglecting agriculture with insufficient backup of food grain in failed monsoons, promoted a command economy over free markets, institutions of higher learning over vigorously implemented primary education, and eulogised big dams as ‘temples of modern India’.

For all his vaunted reputation as an international statesman, ushering in a non-aligned post-colonial world order, Nehru’s disastrous foreign policy mistake was the humiliating, costly defeat in the India-China conflict of 1962.

His ‘Hindi-Chini bhai bhai‘ dream lay in tatters, hastening the onset of ill health and death in 1964. In part, this was because of his poor judgement of colleagues.

Nehru’s patronage, promotion and eventual sacking of V K Krishna Menon as defence minister was his undoing.

Corruption and other scandals also marked his long tenure, with characters such as his private secretary M O Mathai and the able but profiteering Punjab chief minister Partap Singh Kairon. In the end, both had to go.

It is unlikely that Nehru could ever win an election today. What truck could he have with his own party, busily promising a ‘Ram Path Gaman’ (Lord Ram’s Route) and commercial sale of gau mutra (cow urine) in its Madhya Pradesh election manifesto?

Charisma is a difficult thing to define in politicians, but if charm and the common touch are two of its components, here is a quirky anecdote posted by the retired Punjab civil servant S K Mishra.

In 1960, Mr Mishra was enjoying the view of Le Corbusier’s sparkling new secretariat in Chandigarh, feet up on his desk, and reading a novel.

The door was flung open and in walked Prime Minister Nehru and Chief Minister Kairon.

Nehru’s flight had been diverted and he asked for an impromptu tour of the buildings.

“Kya padh rahe ho? (What are you reading?)” asked the PM.

The young officer leapt up and stammered, “P G Wodehouse, Sir.” Nehru was delighted, started discussing Wodehouse characters and described his meeting with the iconic writer.

Later on, as Mr Mishra rose in service he would encounter the PM at meetings, who unfailing asked, “Haven’t we met before, young man?” “P G Wodehouse, Sir.” And, he was rewarded with a twinkling smile.

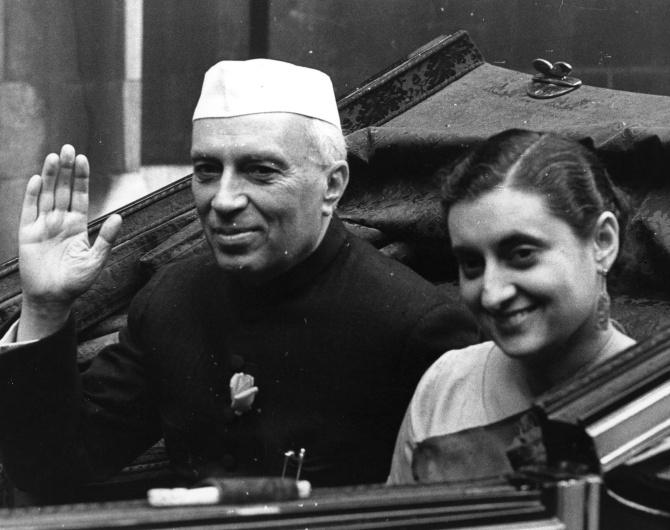

Adored and reviled in equal measure, Nehru’s legacy is obscured but not altogether erased. In the age of ephemeral Instagrams and quick click selfies it is not charmless.

Source: Read Full Article