The deployment of more than 100,000 soldiers belonging to two big armies, strung out over 872 km, in some of the harshest climes in the world, is simply without parallel in military history. The Indian Express on how the Army is staying fighting fit on the Line of Actual Control

“General Winter”. That is the name historians gave to the adversary who routed both Napoleon and Hitler in Russia, more than a century apart from each other.

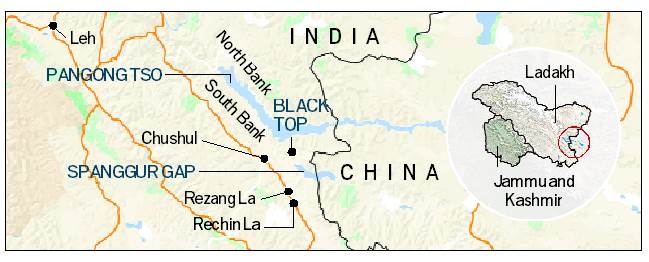

As the Indian and Chinese armies deployed at the Line of Actual Control eyeball each other, sometimes separated by just hundreds of metres, they are up against the same formidable foe, in a way that ambitious military campaigners of previous centuries might not have imagined. Eastern Ladakh is no Russia. Here the peaks go up to 18,000 ft and more. The winter deployment of more than 100,000 soldiers belonging to two armies, strung out over 872 km, is simply without parallel in military history.

“The first problem faced by a soldier in Ladakh is survival, fighting the enemy comes next… The peculiar geography has a major impact on the fighting and its outcome” — these are the opening sentences of the Fighting in Ladakh chapter of India’s official History of The Conflict with China, 1962, that was published more than three decades later.

At this time of the year, the maximum temperature in the forward areas of the LAC is as low as 3 degrees Celsius; minimum can plunge to minus 10 to minus 15 degrees Celsius. December and January will see minus 30 to minus 40 degrees, and snow. Added to this is the wind chill, as the official 1962 history highlighted. “Wind generally starts around mid-day and continues throughout thereafter”, and the combined effect “can cause cold injuries similar to burn injuries”. “Touching metal with bare hands is hazardous.”

With no breakthrough yet on a disengagement proposal from China at the eighth round of Corps Commanders’ talks, and no word on the next round, around 50,000 or so Indian troops are set for the long haul, guarding peaks over 15,000 ft through the winter, mirroring the deployment of the People’s Liberation Army.

Acute Mountain Sickness, high altitude pulmonary oedema, deep vein thrombosis, cerebral venous thrombosis, psychological illnesses — these are just some of the risks they are up against. With falling temperatures will come frostbite, snow-blindness, chilblains, and peeling of skin due to the extremely dry conditions.

Caught in a stalemate

With no further word from China after the initial reports of a disengagement proposal from them in the eighth round of talks, the situation is back to a stalemate. With neither side willing to budge, around 1 lakh soldiers from both sides are going to spend the winter in eastern Ladakh’s peaks. But will it become an annual feature will depend on the diplomatic ability of both countries to resolve the nearly seven-month-long standoff.

Even now, with the most difficult months still ahead, Army sources say, there is daily attrition due to “cold-related” conditions — with many sent back to duty as soon as they get better. While information on altitude-related ailments is confidential, an official source says the non-fatal casualties are “not alarming” and “within the expected ratio”. There have been reported evacuations from the Chinese side too, from the heights of Finger 4.

Major General A P Singh (retd), who headed the logistics for XIV Corps deployed on the LAC between 2011 and 2013, says that till about a decade ago, the attrition rate was around 20%, mostly due to medical-based non-fatal casualties. “Attrition is because of snow, health or failure of oxygen,” he says, adding that soldiers are much better equipped now.

Singh expects soldiers, most of whom were sent to Ladakh between May and September, to be adequately acclimatised. At these heights, that matters as much as who has the superior fire power. Effectively, the Army is in winter deployment at the LAC, though that term has not been officially used. This is the first time.

The 1962 war document states that “nearly equal number of casualties suffered by the Indians were weather casualties”, lauding that it is “a tribute to the Indian soldier that even under such circumstances he fought and fought well”.

While this is the first ever time that so many troops are present in Ladakh at this time of the year, Indian military veterans say things have changed exponentially — for the better. Indian troops, with four wars against Pakistan (including Kargil), one against China, plus a three-decade-long experience of guarding Siachen, the highest battlefield in the world, are used now to dealing with both the heights and the winter, perhaps more so than their Chinese counterparts. Several establishments such as the Kargil and Siachen Battle Schools and the High Altitude Warfare School in Gulmarg train soldiers specifically to fight at heights.

“Our soldiers are deployed at 21,000 ft in Siachen, at 14,000-15,000 ft in Kargil and 14,000-17,000 ft in Eastern Ladakh,” says Lt Gen P J S Pannu (retd), who commanded the XIV Corps from 2016 to 2017. “In both Siachen and Kargil, we have posts that have no access to the outside world once snowfall begins. In the Kargil region, snow accumulates to 15-20 ft… it is highly avalanche-prone. For five to six months, troops are in lockdown positions… This kind of training and resilience is already there in our troops.”

Still, nobody thinks it will be easy.

***

Counting the elements the soldiers are up against, Major General Singh says, “One is the weather, which includes extreme cold and very high-speed winds. The second is the rarefied atmosphere, which is lack of oxygen and a function of the altitude. The third is of course the enemy. All three are treacherous.”

For a soldier arriving especially from a garrison in the plains, the first challenge is the sheer drop of oxygen level. The reduction can range between 25 and 65% — from Leh at 12,000 ft, to Mukhpari heights near Spanggur Gap at over 17,000 ft. On arrival troops undergo a three-stage acclimatisation exercise over 14 days. The first stage involves six days at 9,000 to 12,000 ft, with two days of rest and four days of walks and minor climbs. Stage 2 is four days at 12,000 to 15,000 ft heights, walking and climbing, and carrying loads over short distances. The next stage is four days at 15,000 ft and above, with the same walk-climb routine with and without loads.

In an emergency, this process is cut from 14 to 10 days. But that situation does not exist yet, says an officer. At Siachen in comparison, troops are inducted after a 21-day acclimatisation.

This gap gives the body time to adjust to the low oxygen and not go into hypoxia, which can lead to disorientation, nausea, headache, and if not detected early, more serious complications.

A medical memorandum issued by the Directorate General of Armed Force Medical Services in 1997 said that apart from hypoxia and cold, other factors that can affect performance at high altitudes and cause illnesses are “low humidity, solar and ultraviolet radiation”.

Lt Gen Pannu points out that the low oxygen levels mean efficiency reduces by almost 30-50%. “The soldier’s weight-carrying capability also goes down when, on the contrary, the requirement to carry weight goes up due to the lack of infrastructure.”

The layers of clothing one wears also cut efficacy, Major General Singh says. Talking of the sheer physical exertion needed, including to construct defences and bunkers, he adds that what can be done in the plains in a single day, “takes five to seven days”.

At high-altitude posts, soldiers carry anything between 20 and 45 kg of equipment, says a serving officer who does not want to be identified, depending upon the role the soldier is playing, whether offensive, defensive or on patrol. First and foremost are the weapon and ammunition. The weapon can be a pistol or a carbine, a rifle. If the weapon is heavy like a machine gun, weighing over 20 kg, multiple soldiers help carry it. A company of 60 to 120 soldiers carries at least one Medium Machine Gun, a section (6 to 20 soldiers) a rocket launcher. The ammunition load is divided.

Apart from this, a soldier’s gear includes boots, clothing for extreme weather, a set of inners, a multi-layered jacket, face protection from the cold, goggles to prevent snow-blindness and a helmet. Then there is a ‘sustenance kit’, which includes a sleeping bag, mattress, two pairs of change, toiletries, extra socks, a water bottle, and at least 24 hours worth of emergency, high-calorie cooked rations.

At forward posts, soldiers usually carry tinned food. “You cannot carry logistics to the frontline. Certainly not fresh food and vegetables, and due to low atmospheric pressure, you cannot cook in a pressure cooker for example. But it is not possible to eat large quantities of this (tinned) food. The moment you eat, your stomach pushes the diaphragm up against the lungs and heart, making breathing difficult. Very high calorific value of fruits, dried fruits, chocolates etc are given to soldiers. He enjoys none, and eats only to survive…,” says Pannu.

At the same time, any small movement can mean up to six-10 hours. “If pinned down by enemy fire, a soldier should be able to sustain (on his own),” the officer quoted above says.

Soldiers on the front also need to carry communication sets, the size depending on whether needed for company-to-company calls, battalion communication, or for communication between battalion headquarters and brigade or division headquarters. The sets get bigger with the formation.

***

In the 1962 conflict, the Indian forces across all sectors faced a severe paucity of winter clothing. In his book India’s China War, British journalist Neville Maxwell calls this “inadequate and in short supply”, apart from referring to other problems faced by the men such as the rarefied air, and lack of animals to carry loads. “All supplies, often including water, had to be airdropped.”

Elaborating what this means, Pannu says, “Imagine the air-dropped supplies falling a kilometre or even a few hundred meters from the designated dropping zone. It becomes a nightmare for the soldier who might spend the rest of the day fetching a few kilogrammes of essential supplies.”

Nearly 60 years after the India-China war, India still does not manufacture the insulated clothing required for the heights at which soldiers are now deployed in Ladakh. The clothing is imported at steep rates. Last month, at a public event, Vice Army Chief Lt General S K Saini talked of “a lack of viable indigenous solutions”.

Clothing has to not just ensure that the soldier keeps warm but also not be too heavy. Pannu warns against “heat load”, where the wearer feels hot when he is physically active but not warm enough when he is static.

Referring to the difference between Ladakh, Siachen and Kargil, all of which come under XIV Corps, Singh says that the LAC does not see that much snow, but “is cold, rocky”. “Soldiers here will not carry much snow clothing, but will carry warm clothing.” In comparison, in Siachen soldiers need alpine clothing and mountaineering equipment.

The winds also mean mere tents cannot be much of a protection, Singh says.

Recently, the Army unveiled some newly constructed heated accommodation for troops deployed behind the LAC; sources say facilities to accommodate all the men are in place. These are “smart camps” with barrack-like structures, and including electricity, water, heating, and other facilities. At the frontline though, where soldiers sit on peaks facing the PLA, they live in “heated tents as per tactical considerations”, an officer says.

Pannu notes that in reality a soldier might not spend much time inside the shelters. “He has to patrol, as well as build bunkers and defence work against the enemy’s fire and shelling from ground and air… He has to ultimately dig into the earth and bear the consequences of extreme cold directly.”

***

As deployment of this kind has never been required before at the LAC, many of the forward posts in Eastern Ladakh are being newly established, with no military infrastructure in place. This means, says the officer requesting anonymity, carrying material to create “defensive structures”, “if occupying a new feature”, as the heights on the north bank of Pangong Tso and in the Chushul sub-sector on the southern bank. Digging tools and corrugated galvanised iron sheets are needed to build bunkers and observation posts.

With the road infrastructure patchy, tracks right up to the top exist in only a few places, and soldiers must carry most of the equipment. “We use some amount of animal transport but patrolling is usually carried out on foot, unlike PLA troops who try and reach locations as far as possible by vehicles,” says Pannu.

The Chinese have the advantage of a topography that is like a rooftop — flat, with fewer mountains that are far apart, making the valleys on their side much wider, the veteran officer adds. “They have built highways, much easier to build on that side as they don’t go through so many mountain passes or tunnels. We, however, need to drill tunnels and build roads over passes. We cannot build very wide roads as that would need cutting mountains. The precipitation level on our side is also much more, therefore snow levels are much higher. In the Tibet area, the snowfall is only a few inches because it is very dry there. So they don’t have the challenges of snow blocking passes or tunnels for long period of time,” Pannu says.

While the IAF and Army helicopters have been pressed into service as part of the supply chain, the areas are higher than these are designed for, reducing their carrying capacity and hence meaning more sorties.

***

The other effect on soldiers is harder to detect. Singh talks of “the psychological part of being isolated”, with soldiers cut off from any contact for weeks, even months, from each other. “There is the fear that if something happens, even a helicopter cannot come to evacuate you.”

In order to reduce the exposure of soldiers at these forward posts, troops are being rotated as quickly as every two weeks. Singh says this is possible given the numbers the Army has there now, with a substantial strength in reserve. “If you come back from the post in two-three weeks, you are recouping yourself.”

At Siachen, which has infrastructure in place now at the forward posts as well as the base, a soldier generally spends around 90 days on the front. However, often this rolls over, an officer says, and beyond an acceptable limit, the damage could be permanent. The officer adds that they expect harsher climates in Ladakh, and hence the short rotation times.

“It is not just about maintaining a presence, but also keeping the soldier combat-ready. If you have to fight, you have to keep the health at a certain level. So, an early turnover may be necessitated. He can do a second round after a break,” the officer says, stressing this balance between raising defence and sustenance.

It’s not just the men either. Tanks, artillery systems and other hardware also need to be protected from the cold. “The equipment needs to be hardened and winterised. Repair and recovery are extremely difficult at sub-zero temperatures. In-situ workshops are equipped with warm canopies with bazooka heaters. The oil and radiators are prepared for the winter. All equipment with water pipes faces the problem of freezing, but certain innovations were made (during my time) to ensure water does not remain static in pipes,” says Pannu.

“There are inbuilt SOPs depending on the nature of the equipment, depending on whether they have oil, gas or electronic systems,” says another officer.

Whatever the difficulties, as of now, the troops at the border have dug in for the long haul, quite prepared for the eventuality that there may be no breakthrough towards disengagement. At the moment here is no clarity even on when, or if, the next round of senior commanders meeting will take place. There is precedence that a resolution could take years. In Sumdorong Chu in Arunachal Pradesh, a standoff that began in 1986 took seven years before status quo ante was restored.

While no one can predict if the winter deployment at the LAC is going to become an annual feature, there are murmurs that these are the first straws in the icy winds blowing over Ladakh of the “LoC-isation” of the LAC, meaning the border with China may turn into a front that has to defended in the same way as the one with Pakistan.

And even as nobody wants that, this year could just be the start of a long, cold winter.

About the clothing

- This is special clothing for 14,000 feet and above. Most of the troops on the frontline in Pangong Tso and Chushul would be having a similar kit

- The soldiers carry enough ammunition (to attack/defend, depending on tasks), water bottle and medicine. As part of the unit, they might also have to carry ammunition for larger weapons, medicines, equipment to build defensive structures

- The weight a soldier carries can vary from 20 to 45 kg, depending on the role he is playing and location

Line of defence

Numbers: 50,000-plus;

average deployment is 15,000 to 17,000 usually

Heights: average 15,000 ft,

going upwards of 18,000 ft

LAC length: Over 870 km

in Eastern Ladakh

Weather conditions:

Temperatures 3 degrees to -15 degrees Celsius currently, will fall to up to

-40 degrees; oxygen low by 25% to 65%

Accommodation: Corrugated galvanised iron sheets for bunkers; heated tents on the frontlines; and new ‘smart camps’ with integrated electricity, water, heating behind the LAC

Risks: Acute mountain sickness, high-altitude pulmonary oedema, deep vein thrombosis, cerebral venous thrombosis, psychological illnesses, frostbite, snow-blindness, chilblains

Rotation at forward posts: At some places, as short as every two weeks, to minimise exposure

LAC vs Siachen, Kargil: Desert, not so snowy, with chilly winds, more rugged peaks

Source: Read Full Article