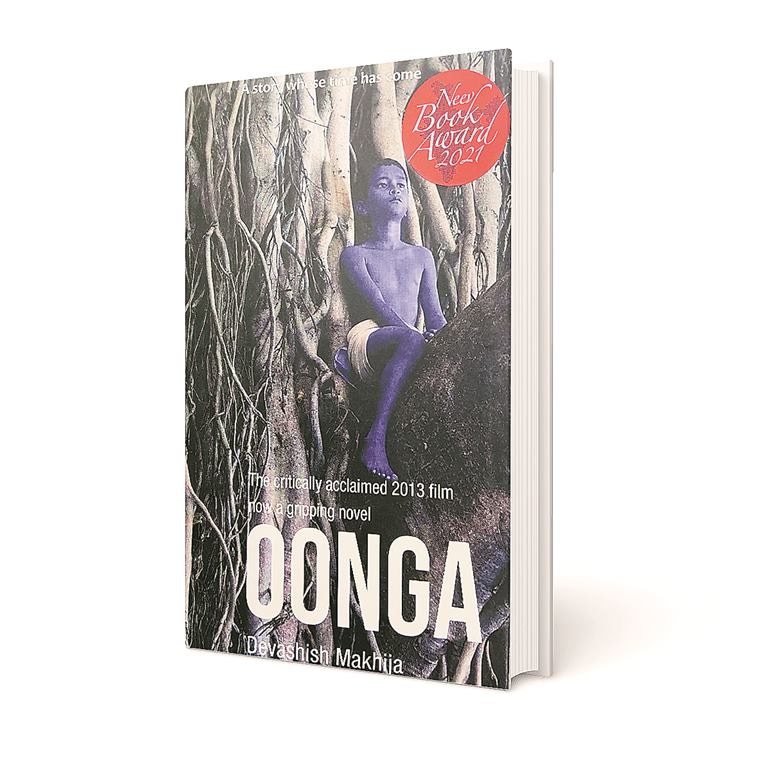

The filmmaker’s debut novel Oonga, an adventure story about a little Adivasi boy fighting to save his village, wins the 2021 Neev Book Award in the YA category

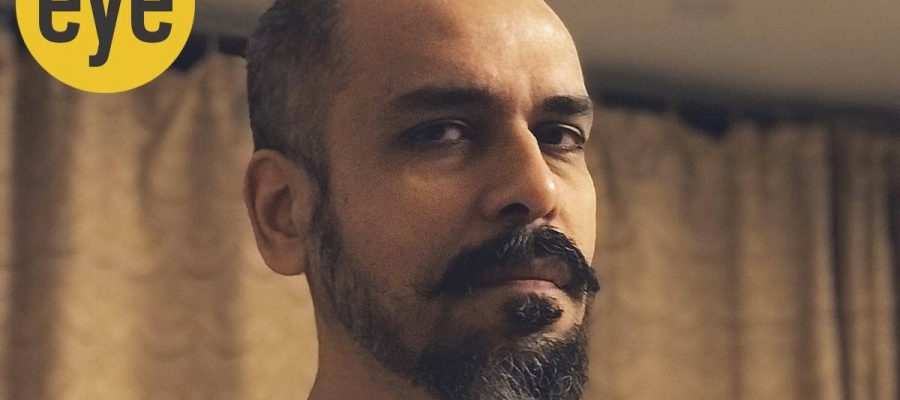

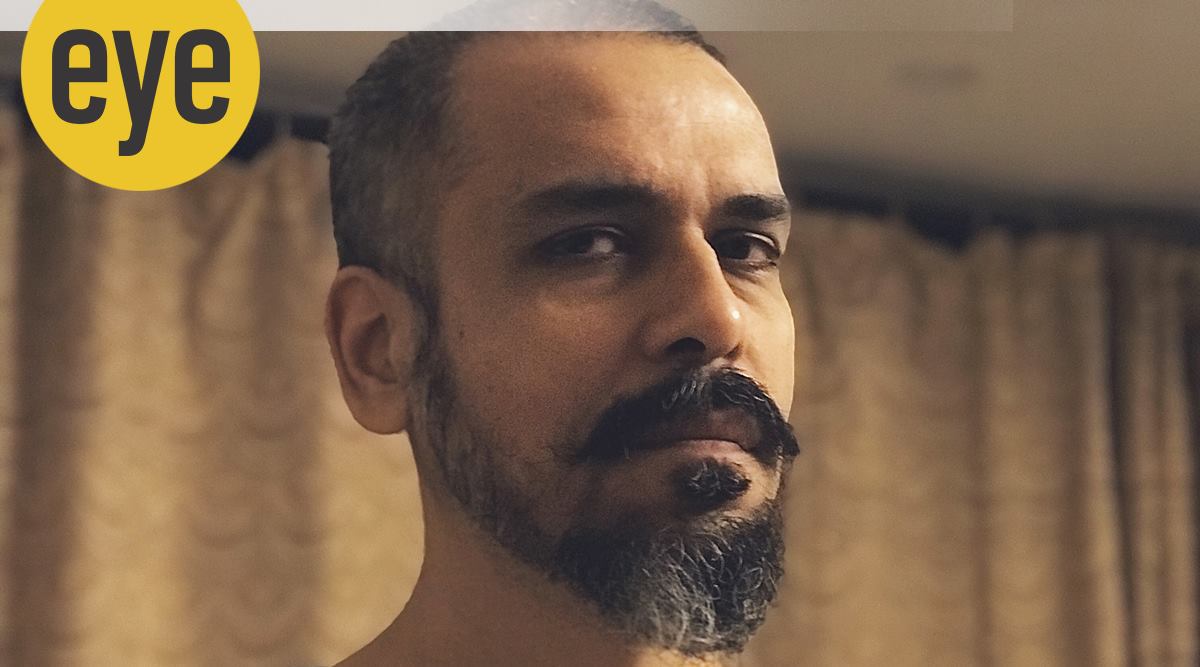

In early 2010, a social worker in Odisha told filmmaker Devashish Makhija about taking her Adivasi friends to a theatre to watch an Odia dub of James Cameron’s film Avatar, released the previous year. They clapped and hooted — until the end; disappointed because their stories almost never have happy endings. This story stayed with filmmaker Makhija, who, having read about the “Naxalite-mining development-tribal conflict” for years, went to Odisha — the south Odisha belt (Malkangiri, Koraput, Niyamgiri, etc.) for over a month — to experience first-hand the lives of the Adivasis. South Korean steel-maker Posco was yet to face resistance from Odisha’s indigenous communities, the Dongria Kondh tribe of Niyamgiri hills were yet to push back Vedanta, Arundhati Roy was yet to publish her essay Walking with the Comrades. What Makhija saw was “they (Adivasis) live in a 24×7 state of dread. They don’t know where they’re going, what they’re going to wake up to tomorrow, what belongs to them, what belongs to the State, whether they belong to the State. There were villages that were not sure that India had achieved independence, that they now belong to a country called India,” he says.

The story of Oonga (Tulika, Rs 295) came out of that time. Written like an adventure story, Oonga first appeared in 2013, at film festivals, but never released in India. When Tulika Books was toying with the idea of a film-to-book story, they approached Makhija. The result was a Young Adult (16-24 years) novel that has just won this year’s Neev Book Award in the YA category. Before this, he’s written a book of short stories and picture books. His publisher had told Makhija he’s dug himself into a hole, Oonga might not fetch an award because it’s “too adult for the young adult, and it’s too young for the adult adult” but the novel succeeds in pushing the boundaries of what’s expected of the category.

Makhija, 42, writes it like Iranian cinema, the big bad world seen through a child’s eyes, with subtexts that work at many levels. One can’t deny a child his fantasies and desires. The eponymous little Dongria Kondh boy wants to become like Rama — like the Avatar-like Na’Vi hero, who wants to become that all-powerful mythological being — to save his village from the enemy. In his mind he believes he’s achieved that end, but, in reality, has failed. Makhija turns to the Ramayana, the source material for Avatar, and subverts it, and unseats “the hegemony that the right-wing Hindutva wants us to pay obeisance to”. Rama, seen through the kids’ perspective, is like a tribal, the child fails because “there’s no Rama, Rama is just an idea. And the little boy appropriated that idea for himself. Like him, each one of us can appropriate Rama in different ways, and nobody can tell us that we cannot do that,” he adds. Blue, the colour of the highest chakra/entity/cosmos, here, smacks of arrogance.

Oonga’s teacher Hemla — the voice of wisdom, standing at the crossroads between the Adivasi villagers, the CRPF and the insurgents — teaches the Kuvi-speaking children to speak in Hindi, the tongue of the oppressors, so that a dialogue can happen. Dialogues are key for problem-solving, and for a dialogue, one needs to listen. The “deaf” CRPF head Manoranjan, an all-encompassing evil, is a metaphor for a system that doesn’t listen. His junior Sushil is powerless, follows orders. Each one is a victim of a larger cycle of capitalistic greed, not of their own making.

The women of the novel act as philosophical conduits. Hemla’s character-mapping seems the most difficult, even at extreme peril to self, her Gandhian stance of remaining non-violent can seem frustrating, when every other character is raging for or at something. But a Hemla was needed else Makhija — if his films (Ajji, Bhonsle) are anything to go by — would have run wild with the insurgent leader Lakhsmi. Hemla is a check not just on the characters’ rage but also of the author’s, who’s known to pour his apoplexy into his stories. “Rage”, for whom, is “a fuel, not a destination”.

For Hemla, Makhija draws from the Adivasi school teacher-turned-politician Soni Sori, including a reimagining of Sori’s 2011 Dantewada police station incident. The explicit writing of violence is well-intentioned, realistic, but can be triggering for whom it’s a lived reality not a perceived one. It is telling of a male gaze, even if the male here is an ally — of the cause, of the Adivasi, of women, of outsiders. The novel despairs with a grim, graphic show of the pitfalls of ownership (not stewardship) of nature, of cyclicality of violence and the hopelessness it begets, but transcends in its portrayal of unsullied innocence, empathy and nature — both human and environmental. The fiction/imagination complements the documentary/real. The novel soars in sections that suggest the supernatural (medicine man Kunja).

The visual elements try to create a sense of a different world for the city reader. If a sprinting Oonga is signalled by the onomatopoeic “thupthupthupthup”, the sound of feet on earth, the linguistic shifts between Kuvi (the Dongria Kondh tongue, of Dravidian origin, is starkly different from the Sanskrit-derived Odia), Hindi and Telugu, spoken by the characters, are suggested by different fonts. Little tribal motifs act as section separators.

Is he appropriating the Adivasi story? Can an upper/middle-class/caste, educated urbanite write about/be a voice for a poor tribal community from a rural area? The novel is orthographic, like a photograph, it’s constitutive of the “self” (the subject matter/Adivasi story) because it is part of the “self”, but it does not claim to represent or express the “self”. Makhija is, to borrow novelist Saikat Majumdar’s words, taking “the political burden of mis-representation – or for that matter, representation of any kind, when speaking as/about the marginalised is always an act of violent infringement”. Makhija, the observer-narrator, like many postcolonial writers, is using the imperial language (English) and the bourgeois form (literature) to tell his story to a wider English-literate readership. He doesn’t speak for his characters. His gaze and voice maintain a self-consciously critical distance. “With every story I’m telling, I’m maybe moving an inch closer to my subject material, but I cannot claim to ever become my subject material because I’m handicapped by my DNA,” says the author who’s simply carrying the Adivasi story to the privileged mainstream in a tongue they understand. And the only way to tackle this argument of aesthetic authenticity and cultural appropriation is to get the book translated in more languages.

Source: Read Full Article