From National Theatre in the UK to the Bolshoi Theater in Russia, some of the greatest arts institutions began to stream recordings of their classic shows online, mostly free, for audiences across the globe.

In September, one of the UK’s unconventional theatre directors, Emma Rice, was streaming her new play, Romantics Anonymous, from Bristol Old Vic to audiences around the globe. The play that revolves around two people — a gifted chocolate maker who suffers from social anxiety, and the boss of a failing chocolate factory, who is so awkward that he needs self-help tapes — was scheduled to tour the US when the pandemic threw all plans awry. Rice, known for brave ideas and strong theatre, decided to have a fully staged live broadcast of the play.

Watching the actors on stage, the audience were transported to the good old days before 2020. And then, one evening, disaster struck in the form of sound problems. The show halted and returned several minutes later with the actors repeating the scene. By then, the audience had glimpses of the making of the play — the director, the tech team and backstage confronting a sudden crisis that, normally, is hidden away. They saw people who otherwise only come out to take a bow at the end. The glitch turned Romantics Anonymous into a richer experience.

Rice was not the only one to adapt to the pandemic. When auditoriums shut the doors, theatre practitioners opened windows. From National Theatre in the UK to the Bolshoi Theater in Russia, some of the greatest arts institutions began to stream recordings of their classic shows online, mostly free, for audiences across the globe. The discovery of Zoom led to experiments such as trans-continental dramatic readings and performances. Actors began to upload performances in quarantine. In India, after a plethora of rushed and forgettable plays on YouTube, a number of experiments emerged that will set the foundation of theatre in 2021 and beyond. We list some of them here:

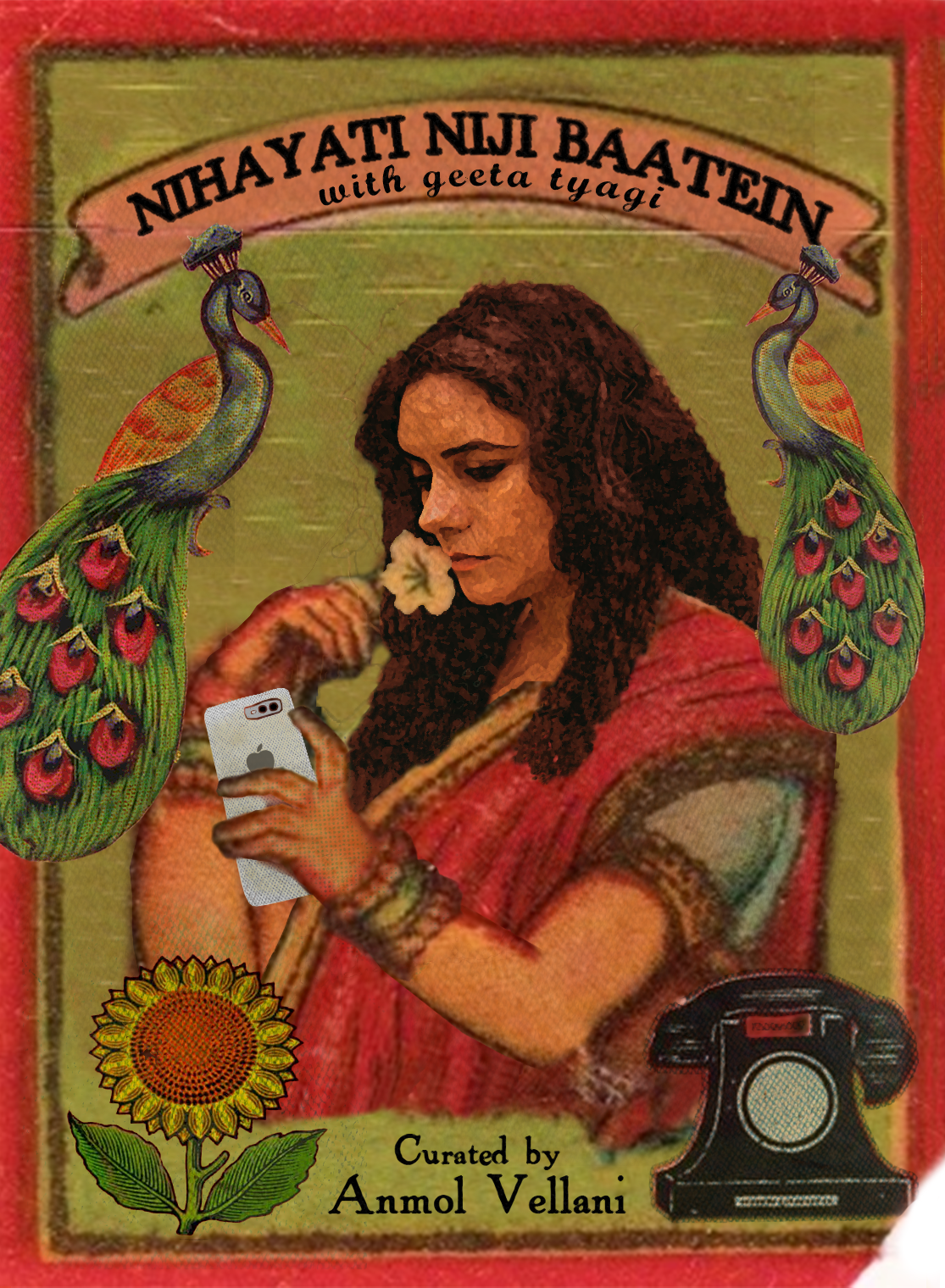

Nihayati Niji Baatein

She is grey-haired, middle-aged and rough-skinned but when Geeta Tyagi uploaded her online tutorial on the art of applying cosmetics — “I wanted to show how, with simple make-up tricks, you can highlight the contours of your face and make it look slim” — she became one of the biggest hits of the star-studded Serendipity Arts Visual, a new digital experience from the five-year-old Goa-based event. Tyagi is played by Mumbai-based theatre practitioner and one of the country’s finest performers, Jyoti Dogra, and the piece is titled Nihayati Niji Baatein.

Tyagi’s attempts to beautify her face segues into questions of aesthetics and aspirations, class and gender, a backstory that hints at violence and present alarms of getting a double chin, among others. Dogra travels through many layers in her 23-minute piece but what makes the work compelling is the simplicity of using social media. Dogra has worked with technology before, in plays such as Black Hole, but not with the internet. For most people, social media is a private space whether they are watching videos or scrolling through posts, so Tyagi looks straight at the camera and addresses the viewer directly, often coming close to screen as if she were a friend sharing a confidence. In its rawness, the home video has the honesty of a woman making a video for the first time and sharing her vulnerabilities. Like any good piece of art, the work does not show the craft and rigour that has gone into it. What remains is the personal connect that Dogra achieved with thousands of people across the country.

The Colour of Loss

In late September, Pune-based theatre actor and director Mohit Takalkar unveiled a new work, titled The Colour of Loss, which took digital theatre to a whole new dimension. Based on the Booker-nominated work of Han Kang, titled The White Book, The Colour of Loss revolves around grief and death and became immediately relevant in the context of the year’s greatest fear. The rehearsals were carried out for two months over Zoom with actors in different cities, before the team met in Pune for the filming. The piece starts with a screen as dark as a hall before the stage light gradually illuminates a glass of water. A woman enters, speaking, just as a close-up of the glass fills a second window on the dark screen. The dark background, complemented by the grey costumes of the actors, represent a void against which the director creates a visual drama. Performers inhabit four windows — a hat-tip to Zoom— in which they carrying out different actions but also interact with one another so that the audience is compelled to follow the movements and stay with the narrative. It was a way to beat the distractions that accompany home-viewing. Sounds also turn into visceral entities, from the chewing of sugar cubes to the pouring of water in a glass to actor Ipshita’s haunting melody. Within a few minutes, the audience gets into the pace and observes the four squares as one interconnected — and disturbing — play. With The Colour of Loss, Takalkar brings the lyricism of his stage productions, such as the award-winning Main Huun Yusuf Aur Yeh Hai Mera Bhai, to the laptop.

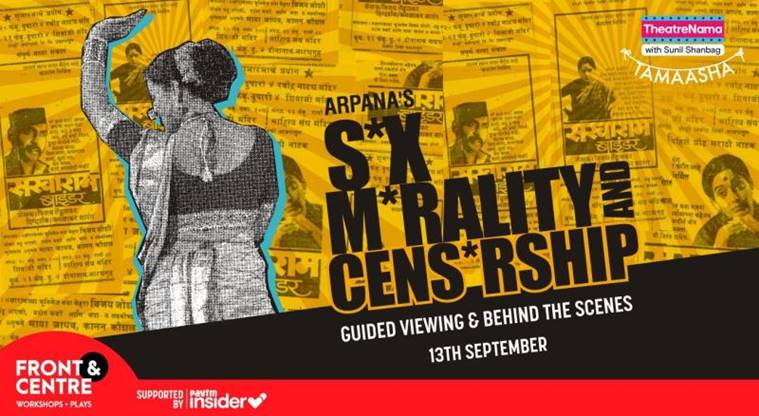

Sex, Morality, and Censorship

Mumbai-based theatre director Sunil Shanbag had some help in taking theatre to a new level during the lockdown — recordings of his play Sex, Morality, and Censorship, his background in documentary films, and a previous first-hand knowledge of the interest that audiences have in the process of making a play. In September, Shanbag’s Studio Tamaasha introduced Theaternama with a guided viewing of Sex, Morality, and Censorship, a play about another play, Vijay Tendulkar’s controversial theatre classic Sakharam Binder that was attacked by the censor board and sections of society in the 1970s.

With writers Irawati Karnik and Shanta Gokhale and actors such as Geetanjali Kulkarni, Shanbag took the audiences on a three-hour journey through issues such as the socio-political realities of the plays, threats to artistic expression and the motivations and experiences of the performers. The style was such that the audience was not watching a recording of a play but being told about it between glimpses of scenes from the play’s previous staging. It is thought that only theatre makers are interested in the nitty-gritty of creating a play but the guided viewing erased this line and, virtually, brought the audience backstage and into rehearsal rooms. This was also possible because of the audio quality, design of the presentation and that, technically, there were few glitches and transitions were smooth. Behind this smooth viewer experience was, clearly, weeks of careful planning and an astute back-end team.

Salt

The play, Salt, is a response to the issue of hunger that will be on one of the lasting memories of the pandemic in India. Bengaluru-based playwright Abhishek Majumdar delved into his experience of becoming a relief worker in the city slums to write a play about a family of three women — a mother and two daughters —who battle hunger with stories. “I have to stretch the story. I stretch because they want the last line to coincide with the last ball of rice,” says the mother. The play has been performed in several languages and was a part of the Ranga Shankara theatre festival. Bengaluru-based performer Pallavi MD, however, performed the script as a solo in Kannada for Firstpost’s initiative of shows on Zoom called FirstAct and revealed the possibility of the new platform. Locked in at home, working by herself, Pallavi used the Zoom windows to show the three women communicating with each other and with the audience. “I shot the different monologues at different times using the Zoom call facility and then edited,” she says. Each woman is distinguished by costume and attitude while physical movements are kept to a minimum. Pallavi holds the audience attention through the 27-minute piece by keeping the focus on one character at a time and gently moving on to the others, while a plate of rice occupies a window of its own at the centre.

The Last Poet

Amitesh Grover is one of the outliers of digital performances in India. Even in the 2G era, he spoke about the internet becoming a part of theatre. The performance maker from Delhi, also a faculty member at the National School of Drama, has been experimenting with the online medium in shows long before the pandemic shut down halls across the country. The Last Poet, a piece of cyber theatre that Grover presented as part of Serendipity Arts Visual in December, bears the stamp of Grover’s understanding of the medium as well as his political commentary. The setting is a dystopian city where a poet is missing — one of the many reminders of poets, thinkers and writers who have been banned, jailed or killed in recent years. A brief film sets the tone before an audience member begins the experience by moving the cursor on a screen on which several rooms float in space. One of these lights up and a room with a performer comes up on the screen. In different rooms, different performers present aspects of the poet as well as their comments on the malaise of the times. Audiences could choose poems to listen to through polls or leave the room for another. While this interaction ensured audience participation, it also left one at the mercy of the majority opinion in the selection of poems. While certain technical aspects need fine-tuning, The Last Poet was a powerful and intense experience that one felt the need to experience several times to appreciate completely. A discussion on the performance can be watched on

For more lifestyle news, follow us: Twitter: lifestyle_ie | Facebook: IE Lifestyle | Instagram: ie_lifestyle

Source: Read Full Article