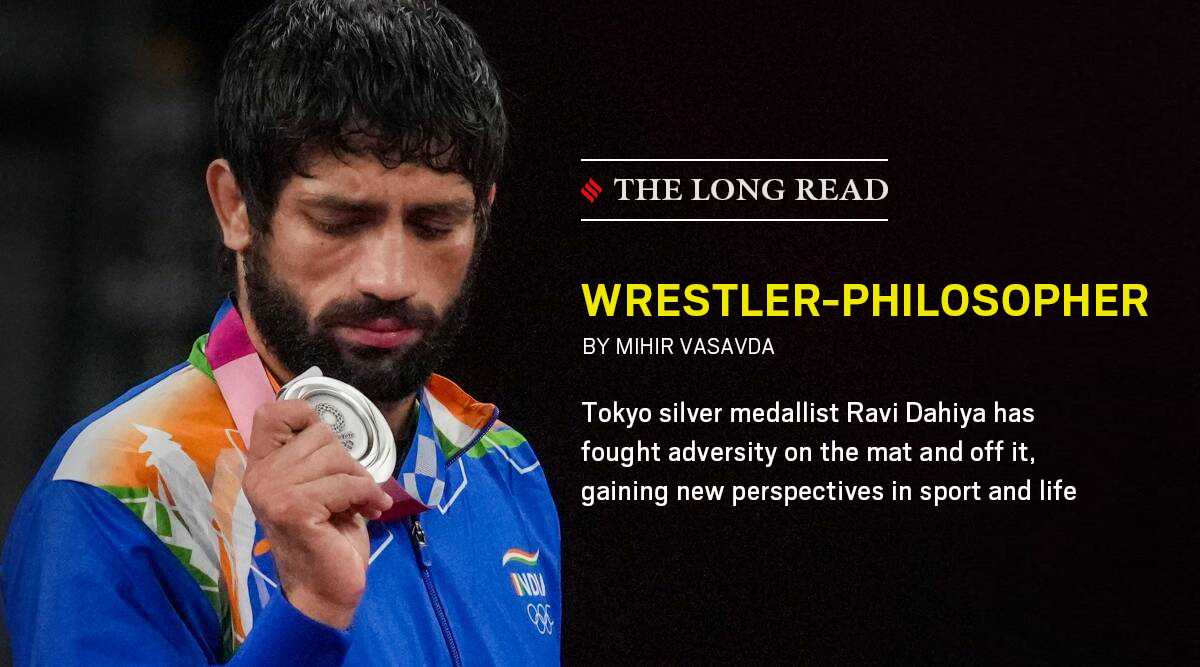

Tokyo silver medallist Ravi Dahiya has fought adversity on the mat and off it, gaining new perspectives in sport and life.

“Struggle,” Ravi Dahiya says, “is continuous. Sometimes, it’s external. Mostly, it’s within.”

The Olympic silver medallist turns philosophical while talking about his job-hunting misadventures.

The story goes something like this: in 2015, after Dahiya started winning medals at junior Asian- and world-level tournaments, the Army approached him with a job offer. But the then-teenaged wrestler rejected it flat out, hoping to get aboard the Railways, like so many of his peers. “My target was Railways so that I could keep wrestling with a free mind,” Dahiya says. “Fauj mein lag jaata (could have got into the Army), but I said no to them.”

As luck would have it, however, soon after he snubbed the Army’s offer, Dahiya says Railways came up with a notification which made only 12th-pass candidates eligible for recruitment. For Dahiya, who had to sacrifice formal education to focus on his wrestling career, this was bad news, and also the beginning of a series of unfortunate incidents.

In 2016, while making a comeback from an injury, Dahiya broke his finger. As he recovered from that, he was down with typhoid. For a wrestler whose game is dependent on strength, the bout with the bacterial infection left him vulnerable. “I lost in the junior nationals, in the selection trials… nothing was going my way,” Dahiya says.

Desperation slowly crept in. On the mat, his career seemed to be headed nowhere. Off it, he had nothing to fall back on. So, Dahiya approached the Army to see if their offer was still open. “‘Aap hi le lo (Please take me)’, I pleaded with them.” But that train, it turned out, had long left the station. “They replied, ‘nahi, ab nahi le sakte aapko (we can’t take you now),’” Dahiya laughs, pauses for a bit as if to introspect, and adds, “you see, we get what we deserve.”

Meet Ravi Dahiya, the wrestler-philosopher.

***

Dahiya talks about one of his toughest phases with the same lightness and simplicity with which he wears the tag of being an Olympic silver medallist.

After he dragged himself to the podium in Tokyo, sullen and sombre-faced, Dahiya wondered ‘what was the point of’ a silver medal. Two months later, his sentiment remains the same. “Theek hai, jeet gaye toh jeet gaye (It’s ok, I won),” he says. “But how much should we celebrate just one medal? It’s not as if there is nothing left to achieve anymore. This is only the beginning.”

The 23-year-old is shy to the point of being dismissive about his achievement but in reality, he has busted almost every myth that many Indian athletes often seek shelter in to justify their under-performance.

As a little-known teenager, he gate-crashed the 57kg weight class, one of the most crowded and fiercely competitive categories in India. He upset some established names from Haryana, Delhi and Maharashtra to break into the team for the 2019 World Championship, where he won a bronze medal in his maiden appearance and secured an Olympic berth.

In Tokyo, Dahiya shattered the commonly-held notion that it’s tough to medal at debut Olympics. But he didn’t care for reputations, showed zero nerves and bulldozed past some of the world’s top wrestlers, including a cinematic takedown of Asian champion Nurislam Sanayev, before ultimately losing to two-time world champion Zavur Uguev in the gold-medal match.

Come to think of it, Dahiya is still a sophomore in world wrestling. Yet, his opponents dread him because he ‘keeps coming back at you’, irrespective of the match situation. And his ability to stage comebacks is already the stuff of legends, at least in Indian wrestling.

Ask Dahiya about this and he quips, “bas, maalik ka aashirwad aur mehnat (Just the Almighty’s blessings and hard work).”

It’s almost impossible to tell what Dahiya is thinking on the mat. And he is inscrutable outside it. But the morsels of profound philosophy he throws are a window into the thought process of one of Indian sport’s most interesting minds.

***

“How we think depends a lot on the company we keep,” Dahiya says. “In my case, I am surrounded by family and friends who keep drilling sense into me. You know, after I got the silver, they told me, ‘okay, you won a medal in your first Olympics but if let this get into your head, you’ll be left behind. So, remain grounded.’”

That, he adds, comes naturally to him. “I have reached this far after years of struggle, which has made me humble,” Dahiya says. “Luckily for me, I had people who held my hand and showed me the right direction at crucial junctures. It’s essential to have such mentors.”

His ‘biggest period of struggle’, Dahiya says, was in 2010-11. It had been a couple of years since the young boy had left his home in Haryana’s Nahari village to join the akhara at Chhatrasal Stadium, a wrestling nursery in North-West Delhi. This was the time when there was a huge uptick in wrestling around these parts after Sushil Kumar, a Chhatrasal product, won the bronze medal at Beijing 2008. And in the glut of wrestlers, Dahiya was lost.

“I had absolutely no results to show and my family had also lost patience,” Dahiya says. “They came to the stadium one day and said, ‘chalo ghar (let’s go home).’ My bags were packed and I was just about to leave when one of my earliest mentors, Arun, stepped in.”

It helped that Arun was from the same village as Dahiya and somehow, he convinced his parents to let him stay back. Then, Arun took Dahiya for some tests, which revealed that he had massive iron deficiencies. “That intervention helped. We course-corrected immediately and there was an instant improvement in my performance. I won gold at nationals, then in Asia… things were finally starting to work out.”

You know things are working out especially when Sushil spots you. Now behind bars for alleged murder, it is said that the two-time Olympic medallist has an unerring eye for talent. In 2015, Sushil recommended Olympic Gold Quest (OQG) to sign Dahiya along with another wrestler, Deepak Punia, who came agonisingly close to winning a bronze medal at the Tokyo Olympics.

“Sushil called him an exceptional talent, and praised his work ethic,” OGQ’s chief executive Viren Rasquinha says. “Ravi was so shy even back then that when Sushil and I had a meeting with him in 2015, he would look down while talking and did not speak more than a word or two.”

Gradually, Dahiya forged a reputation of being a no-fuss wrestler, someone who was not concerned if he was training in India or abroad, under an Indian coach or a foreigner. He was content as long as he had a mat to train and a meal to eat. But on the mat, he was never satisfied no matter what he achieved.

“It’s something a motivator, this person named Vikrant, has instilled in me. I have been in touch with him for a couple of years, and he’s always pushed me to achieve more,” Dahiya says. “One line he said after the 2019 World Championship has stayed with me: ‘be happy with what you achieve, but don’t be satisfied.’ That’s what I believe in now.”

***

The struggle is now within. The Tokyo silver has been a life-altering moment for Dahiya. The challenge, he says, is to continue living the same simple lifestyle without too much fuss. “If I want to continue competing for long and win more medals, I’ll have to live a normal life,” Dahiya says.

So far, he’s balanced it well. Dahiya’s rustic charm has made him a showstopper at a fashion show. He has spoken to students about the importance of proper education. And he has travelled to holy cities for some solitude, his idea of a vacation. But now, he is back where he belongs: on a wrestling mat at the Chhatrasal Stadium, where his medal has lifted the gloom that had settled following the incidents of violence earlier this year.

Munesh Kumar, Dahiya’s physiotherapist, says one glance around Chhatrasal is enough to understand the impact he has had on the young wrestlers. “For the wrestlers, it was tough to focus on their training after the incident. But Ravi’s medal lifted everyone’s spirits,” Kumar says. “When he returned, there were huge celebrations and a lot of young wrestlers are once again motivated to work hard and train.”

Chhatrasal is also where Dahiya’s job search finally ended. In 2019, he did get his dream job with the Railways. But after the Tokyo Olympics, he was offered the post of assistant director at the stadium, which he calls his home. Dahiya isn’t interested in occupying the seat just for the sake of it. If he gets free time, he wants to educate himself properly to become a ‘good mentor’, just like he’s had over the years. “A good athlete can get a good post. But you also need the knowledge to be of help to others,” Dahiya says. “Whatever you do, your target has to be clear.”

Right now, though, his target is just one. “In Tokyo, I had no doubt that I would win a medal. Just that, I had targeted a gold. I am not saying my opponent did not deserve it. But I just hope that in Paris, I will be more deserving.”

Source: Read Full Article