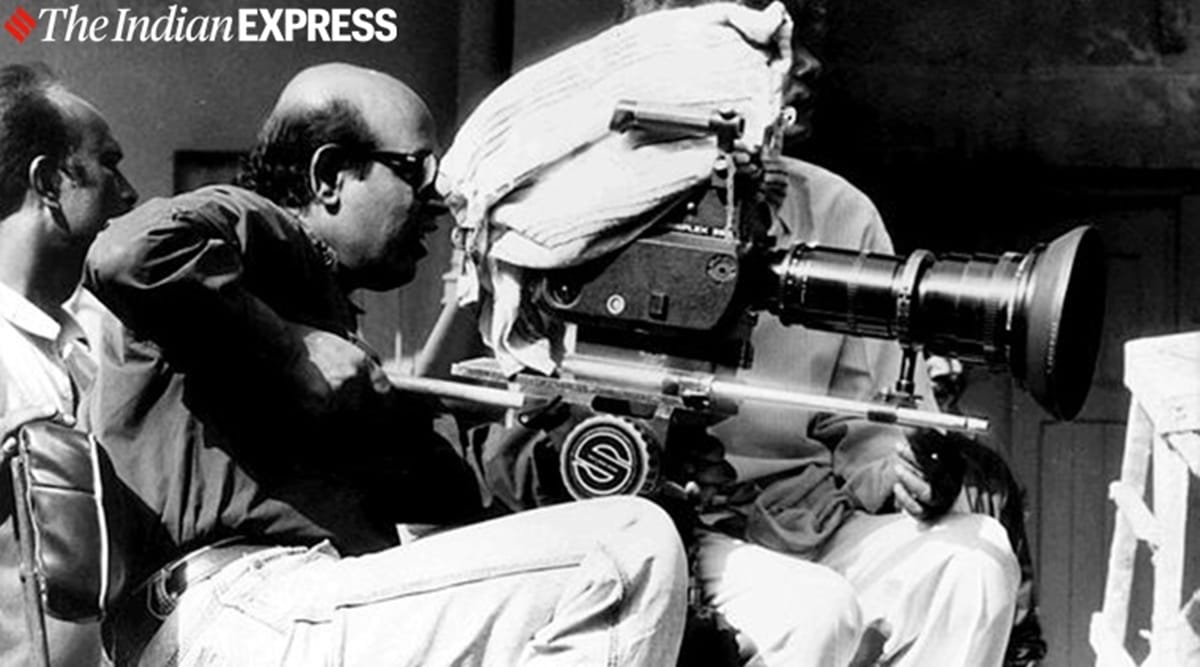

Buddhadeb Dasgupta’s best work was full of stirring beauty, uneasy people, and unsettling situations, and kept you swinging between the real, unreal, surreal.

Get email alerts for your favourite author. Sign up here

Buddhadeb Dasgupta’s cinema was a unique mix of realism and lyricism, set in landscapes which could pass for the here and now, as well as time gone by. Often, trying to decode visuals which were likely to recur in his movies –vertically challenged people, ‘baul’ singers, flute players, merry mendicants, men with sly eyes, women with soulful faces — you would be transported to a place which you knew was familiar, but also strange. Dasgupta’s best work was full of stirring beauty, uneasy people, and unsettling situations, and kept you swinging between the real, unreal, surreal. For a man who abhorred manipulation in movies, he was a master manipulator of time and place.

Dasgupta, who had been ailing for some time, passed away in his sleep early this morning. He was 77. He won the National award for Best Film many times over, as well as for Best Bengali film. He was also a well-regarded poet, which is why there are so many poetic touches in his frames.

The self-taught filmmaker, who quit teaching economics at a Calcutta college because of his disillusionment with bookish precepts, brought his clear-eyed vision into his early movies [ ‘Duratwa’ (1979), ‘Andhi Gali’ (1984) ]. Bengal’s long, complicated tryst with the Naxal movement found a reflection in these films, but those who carried the Naxalite banner weren’t treated as heroes.

Middle-class pragmatism, which aspirational Bengal was veering towards, was at odds with Naxal ideology, and Dasgupta moved away to a different aesthetic, there to find his own true voice.

The 1989 ‘Bagh Bahadur’ was about dancers who painted themselves like tigers, stripes, whiskers and all, and moved from one place to another in search of succour even as they provided entertainment to the local population.

Dasgupta had spent a great deal of his childhood around and about these dancers in Kharagpur, and he poured that deep knowledge and empathy into the character of Ghunuram, tiger dancer non pareil. Pavan Malhotra, who played Ghunuram, often speaks about the many excruciating hours he had to sit still to let the paint dry, enough for him to be able to do the dance movements without it cracking.

Malhotra danced with such grace that you couldn’t take your eyes off him, and the film turned into an instant classic.

A year later came ‘Uttara’ (2000). The opening is unforgettable. In the far distance is a hilltop. On its highest point is a girl, surrounded by grazing animals. A jeep with three men comes careening into the frame, their eyes changing as they see the lonely young woman. A whole flock of short people come down the hill.

What is the connection between these people? Is there any at all? Dasgupta makes you work for the pay-off, and you are the richer for it.

‘Bagh Bahadur’ was made in Hindi. ‘Uttara’, like his earlier films, was in Bengali. Dasgupta switched quite easily between these languages because he was familiar with both. He also reached out to actors who were comfortable in both languages: Mithun Chakraborty and Rahul Bose play long-lost father and son in ‘Kaalpurush’ ( 2005), and some of those sequences between them are lovely.

Not all of Dasgupta’s later films were as successful with this deliberate infusion of whimsy and reality, but the director never lost his appetite to go after the unexpected. In his last released film, ‘Anwar Ka Ajab Kissa’ — which was made in 2013, but came out on a streaming platform only last year — Nawazuddin Siddiqui plays a bumbling gumshoe, spying upon illicit lovers and other worthies who have something to hide.

It’s a delicious premise, but the style feels tired. But even here, you could tell that it was Buddhadeb film: a wry observational stance is a great place to see the world go by.

Source: Read Full Article