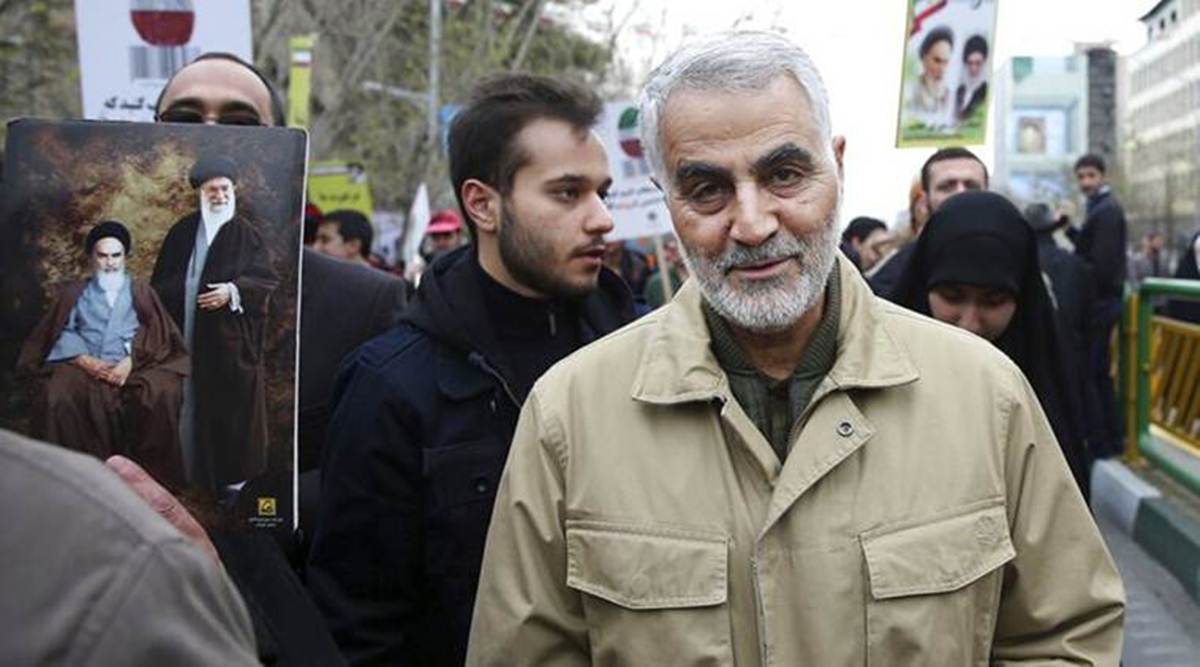

Iraqis fear a flare-up in sectarian tensions after Iran vowed revenge for killing military leader Qassem Soleimani in January. But some fear that factions within the Iraqi security forces could also threaten stability.

January 3 marks the first anniversary of the death of senior Iranian military leader Qassem Soleimani. The major general was killed in a US-directed drone attack while visiting Baghdad.

In a statement earlier this month, Iran’s religious leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, repeated his country’s desire for revenge. For Iraqis, this may well pose a danger.

“We fear that Iraq will become the arena for the settling of scores and that this will only hurt innocent Iraqis,” said Nazem Shukr, a civil servant from Iraq’s Anbar province. “We’re worried that Iran will retaliate, America will react and then we’ll go back to square one, like in 2006 when there were sectarian tensions and many were killed,” he told DW.

“Nobody thinks there will be outright war but some Iraqis believe Trump would like to target the Iranians — or their allies inside Iraq — in the last few weeks of his term,” says Hussam Zuwain, a civil-society activist from southern Najaf province. “We’re worried about American reactions.”

Rise in attacks on US bases

Since Soleimani’s assassination at the beginning of the year, there have been a series of rocket attacks on US bases around Iraq, as well as on the Green Zone, a high-security district in Baghdad housing the Iraqi government and foreign embassies.

There are 3,000 US troops left in Iraq. In November, the US announced plans to draw those down to 2,500 by January 15, and non-essential staff have already left the US Embassy. US President Donald Trump has tweeted that the death of an American citizen would be a red line, requiring retaliation.

Neither country wants war

The situation was probably more dangerous earlier in 2020 straight after the assassination, says Iraq-based researcher Sajad Jiyad, a fellow at The Century Foundation think tank. At that stage, Iran was firing rockets directly at US bases in Iraq.

But since June, the aggressive rhetoric has calmed, he told DW. In a recent interview, Iran’s ambassador to Iraq pointed out that revenge for Soleimani need not involve military intervention. Observers believe that Iran is biding its time, waiting for the change of administration in the US.

Earlier this month, the top US general in the region, Kenneth McKenzie, also told American media that, although there was “heightened risk,” he did not think Iran wanted war.

The real danger it seems, comes from inside Iraq, from increasingly delinquent militia groups.

Iraq’s deep state

When the extremist Sunni Muslim group known as “Islamic State” (IS) began advancing in 2015, a call went out for volunteers to defend their own communities. It led to the establishment of informal militia groups, mostly consisting of Shiite Muslim locals. The volunteer fighters were seen as heroes.

But after the crisis ended, the majority of these paramilitary groups did not disband and, over time, they have evolved to be part of official Iraqi security forces, known as the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF).

Some PMF factions, however, are accused of using a mixture of crime, corruption and violence to dominate parts of the country. And as a network, the PMF are seen as powerful enough to challenge the Iraqi government itself.

The PMF are also split along ideological lines. A large number of fighters pledge allegiance to Iranian, rather than Iraqi, leaders. The conservative Shiite Muslim theocracy in Iran has provided them with everything from wages and weapons to spiritual and military guidance, and Iran-allied factions are now known as “the loyalists.”

New generation of militias

After the assassination of Soleimani and Iraqi paramilitary leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, who was also killed in the drone attack and who was possibly even more important for Iraqi fighters, the PMF fractured further.

More extremist loyalist groups — in particular, Asaib Ahl al-Haq and Kataeb Hezbollah — have seen internal leadership squabbles, have been competing for influence and generally became less popular with ordinary Iraqis, according to observers. They often deny having anything to do with rocket attacks on American or Iraqi targets and generally toe Iran’s political line.

Yet the rocket attacks have continued. Analysts suspect that a new generation of militias — smaller, lesser-known splinter groups — are doing what could be described as the established groups’ “dirty work.” One of the new group, Saraya Qasim al-Jabarin, has taken credit for the attempted bombing of a US logistics convoy on December 27, for example.

Militias avoiding public criticism

“The method is to create fake groups, claim attacks using these group identities and thus mask [established militias’] role in the attacks,” writes Michael Knights in a report for the Combating Terrorism Center at US military academy West Point, which advises government departments and other institutions.

It means that the established loyalist factions can remain part of Iraq’s security forces and avoid public criticism, he argues, and since early 2020 onwards, numbers of the new groups have “skyrocketed.”

Iraqi researcher Jiyad isn’t sure the new groups are simply fronts for older ones. “My instinct is that they are operationally independent from PMF groups,” he says. This makes them harder to track. “There is concern that these groups are more reckless. There’s much less oversight and that’s a worrying situation.”

On January 3, this is where the danger lies, Jiyad confirms. “It comes from these new groups who are not following policy — so to speak — from Iran,” he told DW.

US Embassy demonstrations likely

“The situation in Iraq is precarious for many reasons,” concludes Lahib Higel, senior Iraq analyst at the policy institute Crisis Group, noting the deteriorating economic situation and ongoing anti-government protests as destabilizing factors.

She thinks locals are right to be worried about January 3. “Nobody knows for sure what’s going to happen but you can assume that there will be a demonstration outside the US Embassy,” Higel told DW. “I think it will be controlled.” But, she adds, it really depends who turns up and whether they make any “mistakes”.

Source: Read Full Article