When I was born in 1924, I had a heart murmur. They didn’t think I was going to live past 3 years old. And the anxiety of possibly losing me at a very young age made my mother hover over me from the moment I was born. She used to drive me crazy. [laughs] But now here I am at 96 years old, outliving my mother, father, sister, and brother.

I grew up on the east side of New York City in a neighborhood that was known as the slums back then. It wasn’t easy to raise a family there, but my mother made sure we were in church every Sunday, and often every other day of the week too. On Wednesdays there were prayer meetings. On Saturdays we cleaned the church. I taught Sunday school and played the piano and the organ as well.

I loved performing in church, and when I got older, I dreamed of going into show business. But my mother didn’t like that idea. She told me if I was going to do that, I had to leave her house. And so I did. It was the mid-'50s, and my friend who worked for the telephone company said I could stay in her extra bedroom. Luckily, we wore the same size clothes, so when I started getting auditions, I borrowed dresses from her. And that’s how it went until I got on my feet.

After I moved out, my mother didn’t speak to me for years. She was concerned that I was going to live a life of sin—that’s what she thought show business was all about. But I was always determined to prove her wrong. And so my mother became my greatest source of drive in life. I thought, “I’ll show her!” I didn’t know what was going to happen next, but I knew I had a background that was cemented in the church, and that doesn’t leave you. And that drive has never left me either.

When I look back now on the many decades I’ve spent in this business since then, there is one moment that I consider to be a turning point. I was in Philadelphia promoting Sounder [in 1972]. After the film played, a Caucasian reporter said to me, “Ms. Tyson, I never thought of myself as the least bit prejudiced, but as I watched the film, I could not believe that your son was calling his father ‘Daddy.’ That is what my son calls me.” I was taken aback, of course, and it took me a few minutes to absorb what he was actually saying. What I realized was that he thought there was something radically wrong with a Black child calling his father a name he thought was reserved for his own kind. It was appalling to me. This man knew nothing about our shared humanity. But during another press stop in the Midwest, a second reporter’s comments reinforced this same notion, the one that lives at the center of all bias: You are different. And that difference makes you inferior.

I wanted to alter the narrative about how Black people, and Black women particularly, were perceived by reflecting their dignity.

That was when I realized I could not afford the luxury of being an actress who takes on any kind of role. Right then and there I decided my career would become my platform and I was only going to do projects that addressed the issues I found offensive to me as a Black woman. I wanted to alter the narrative about how Black people, and Black women particularly, were perceived by reflecting their dignity.

During the civil-rights movement, instead of other kinds of demonstrations, I protested by using the characters I inhabited. When I was presented with a script, one of two things happened. Either my skin tingled with excitement because I could address an issue that I was unhappy with, or my stomach churned because I knew I couldn’t take on a character that didn’t mirror the times and propel them forward.

My skin tingled the most for my character Jane Pittman [from 1974’s The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman]. Her journey from bondage to freedom captured the struggle of Black Americans from the end of the Civil War in the 1860s through the civil-rights movement in the 1960s. What she did at an age when people are usually retired was incredible. In 1962, at 110 years old, she still pushed on. And it seemed that all who watched were touched by her story. Michael Jackson even called me “Ms. Jane” after that. [laughs] The same goes for my character Binta, from Roots. No matter where I go, everybody talks about the power of that story. People ask me about it all the time when I’m abroad, and for years crowds would gather along the road and chant, “Roots, Roots, Roots!”

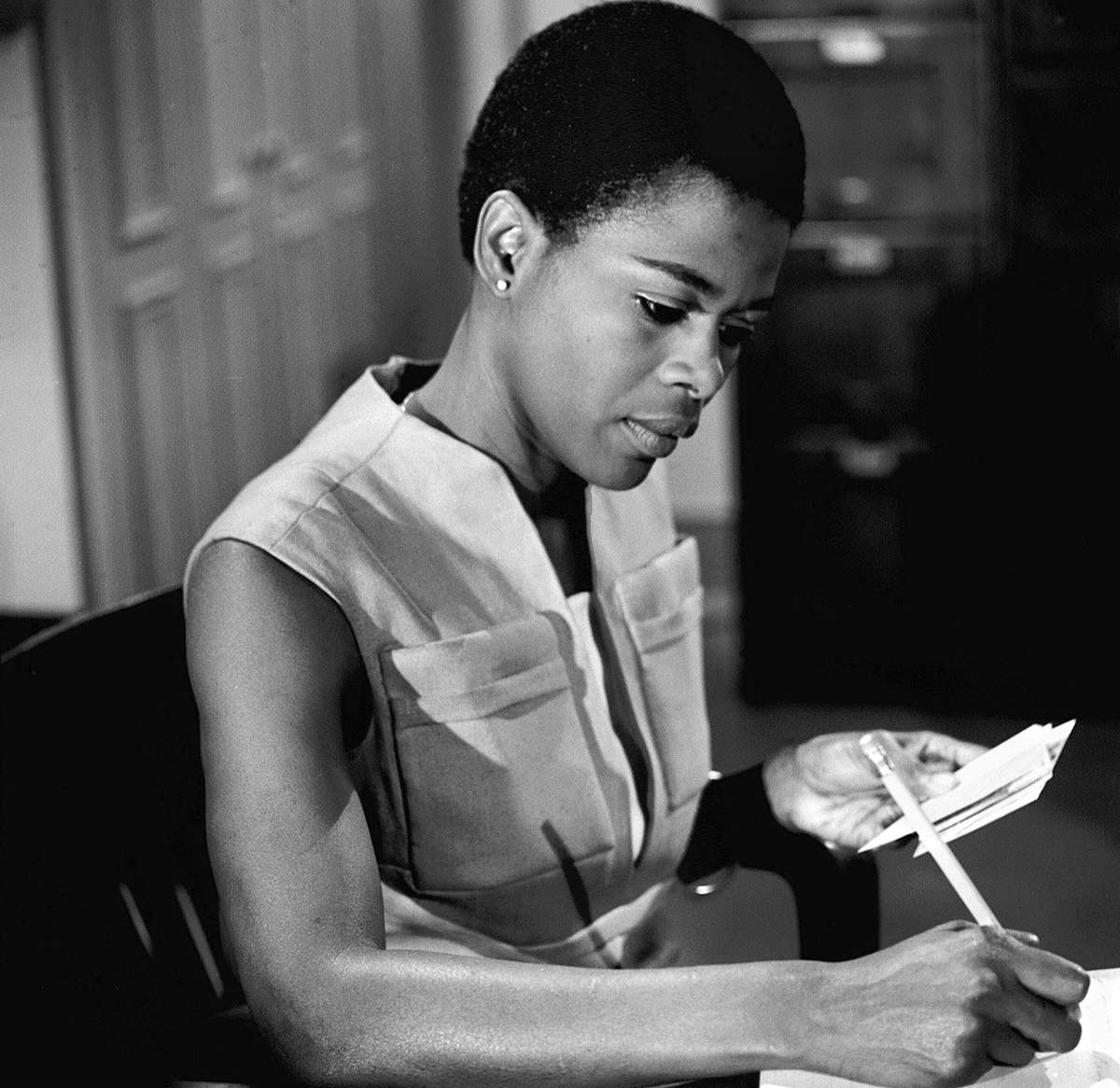

To tell you the truth, I’m still amazed when certain things from my career are attributed to me, like the natural-hair movement. In 1962 I was asked to do a live episode of Between Yesterday and Today, which was a CBS Sunday morning drama, where I played an African wife who wanted to preserve her cultural heritage in the United States. When I auditioned, they told me to leave my hair straightened, but I knew this woman would wear her hair natural. So the night before we taped, I went to a Harlem barbershop that was frequented by Duke Ellington and asked them to cut my hair as short as they could and then shampoo it, so it would go back to its natural state. When I arrived at the studio the next morning, I kept my head covered as I got my makeup done and put my costume on. When the director yelled “Places,” I took the scarf off, and everything stopped. He walked up to me and said, “Cicely, you cut your hair.” And I thought, “Oh lord, he’s going to fire me.” [laughs] And then he said, “I wanted to ask you to do it, but I didn’t have the nerve.”

We went on with the show, and I became the first Black woman to wear her hair natural on TV. I then starred on the CBS show East Side/West Side with the same look. Letters began pouring into the studio, and hairdressers started complaining that there’s some actress who cut off all of her hair in a show, and now they’re losing their customers because of it. [laughs] Some people celebrated the choice. Other people told me I was in a position to glorify Black women, and I had disgraced them instead. I was not trying to be groundbreaking that day, but that one small choice still has effects today.

In fact, the wonderful Viola Davis, who I worked with on How to Get Away with Murder, wrote in the forward of my memoir that watching me in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman gave her permission to dream. There is no greater compliment. But more than anything, I hope that the next generation of actresses learns from me that to your own self you must be true. You cannot go by anybody else’s ideas. And if you don’t feel what your character has felt during the course of their years, you can’t make someone else feel it. When I did the play The Trip to Bountiful, women would come up to me with tears in their eyes telling me how it clarified the injustice they had encountered and their mothers had encountered. But I could only give them that because I had felt that injustice myself.

Life is a journey, and I will always be searching to find out who I am, what I am, and why I am.

In many ways, I’m only now beginning to explore my own identity. I have a performing-arts school in East Orange, N.J., and not that long ago I was speaking to a group of children there. A young girl about 13 years old said to me, “Ms. Tyson, now that you’ve made it, what are you going to do next?” [laughs] I said, “Sweetheart, let me tell you something. The day I feel that I have made it, I am finished.” I hope I never, ever feel that way. Life is a journey, and I will always be searching to find out who I am, what I am, and why I am. And really, what’s all the fuss about? That’s what Miles [Davis, Tyson’s ex-husband] used to say about himself. He’d say, “What’s all the fuss about? I’m just blowing on a horn.” [laughs]

This is a massive world, and there is no part of it that I have seen. I’m always looking for it, wanting to hear it, see it, feel it. That’s what life is — it’s to live and to learn from. The day we cease to explore is the day we begin to wilt. So now when people ask what’s next for me, I say, “I’m just waiting for the next one.” When it hits me, I’ll know it.

Tyson’s memoir, Just as I Am, is available now. This essay appears in the March 2021 issue of InStyle, which will be available on newsstands and for digital download in February.

Source: Read Full Article