The central government does not identify deaths due to manual scavenging and instead calls them deaths due to hazardous cleaning of septic tanks and sewers.

Forty-year-old Rakesh from Mandawali in East Delhi still remembers the day he lost his nephew and two colleagues, who had entered a 15 feet deep septic tank to clean it. The men found themselves unable to breathe shortly after they entered the tank in Lajpat Nagar, and didn’t make it out alive.

The August 6, 2017 incident is one of many the national capital has seen of deaths involving manual scavengers over the past few years. According to Bezwada Wilson, national convener of the Safai Karmachari Andolan, 472 manual scavenging deaths across the country were recorded between 2016 and 2020, and 26 so far in 2021.

This is in sharp contrast to what Union Social Justice and Empowerment Minister Ramdas Athawale told Parliament on Thursday. “No such deaths have been reported due to manual scavenging,” he said.

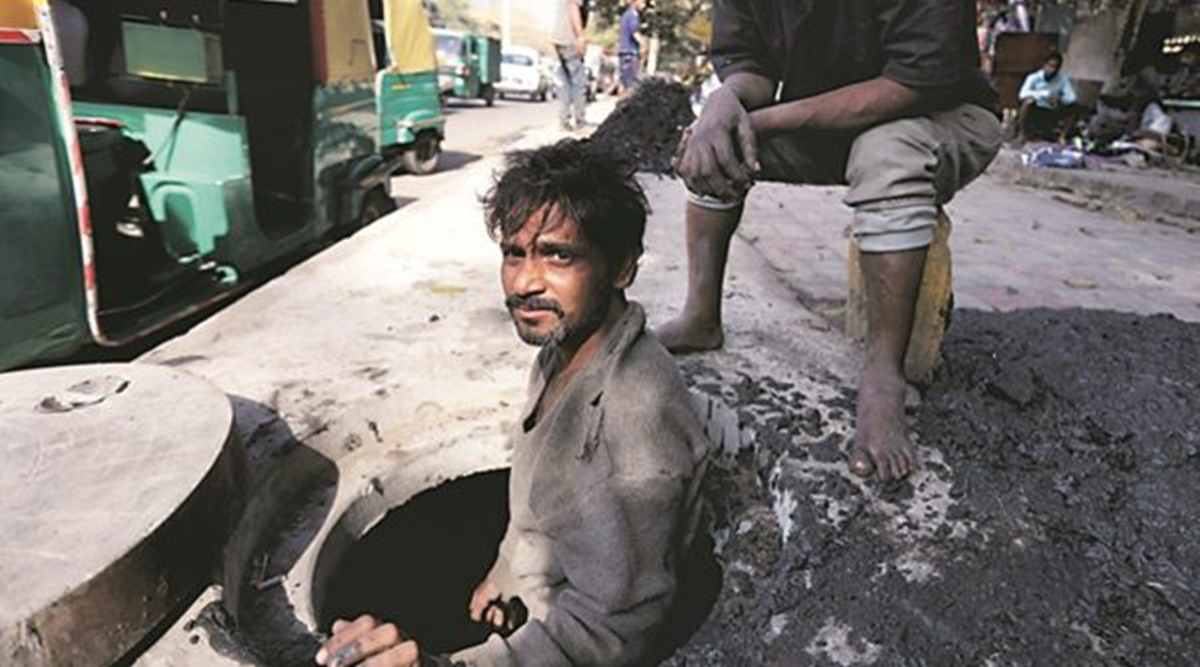

The central government does not identify deaths due to manual scavenging and instead calls them deaths due to hazardous cleaning of septic tanks and sewers. Wilson, however, said the definition of manual scavenging is clear and that the Centre is trying to manipulate it. It includes anyone who cleans human excreta, and this naturally includes those who have to enter manholes and tanks to clean it, he said. “Manual scavenging is already inhumane. It is even more inhumane to hide the data. These are the most vulnerable, voiceless people. Instead of saying that there is no data available, they claimed that there have been no deaths in the last five years.”

Another reason for this lack of data is civic and state authorities not acknowledging the issue exists, let alone keeping a record of the deaths.

It was in August 2018 that the Delhi government, for the first time, acknowledged the existence of manual scavengers in the city, based on a survey that covered just two of Delhi’s 11 districts. “The survey was never completed. Moreover, agencies mostly take cover behind the fact that it is difficult to keep count as government departments cannot officially engage manual scavengers. Deaths during sewer cleaning exercises are usually attributed to lapses on the part of third party agencies,” a social welfare department official had told The Indian Express.

Sanitation workers and unions representing them maintain that both private contractors and civic bodies still follow the practice of asking workers to enter storm water drains and sewer lines to clean them, often without safety gear.

Rajendra Mewati, general secretary of the united front of MCD employees association, said that the practice is particularly prevalent in areas where sewer cleaning machines cannot enter or are not able to get the job done.

Rajesh Beniwal, president of the Delhi Pradesh All India Safai Mazdoor Congress, said: “There are jhuggis where all excreta clogs nullahs and our people have to enter and clean it. Even drains where polythene is stuck are cleaned by hand. We haven’t got gumboots and other safety gear for years.”

According to MCD data, more than 2400 sanitation workers died before reaching the age of retirement in the period between 2013 and 2017 — though officials attribute it to causes other than work hazards.

Recalling the Lajpat Nagar incident, Rakesh said: “We used to work on a contract basis with private companies. That day, there was a deep tank we had to clean. Anu, my nephew, along with two others, Mona and Joginder, went inside. Because there was so much gas, I tried to go in but returned halfway. It was impossible to breathe,” said Rakesh. He added that they were not given any safety equipment — a theme common to almost every such incident.

He said that they used to work for Rs 10,500 a month and “never had an option to say no” because this was the only work they knew. He said he has been doing the same work for 30 years, and while the incident left him panic-stricken, he said he had no other option but to continue. An FIR had been registered under Section 304 of the Indian Penal Code.

On March 24 last year, days after the nationwide lockdown was imposed, Radhyasham’s brother went into a septic tank to clean it because he “needed the money”.

“My brother, Prem Chand, used to work as a caterer on a contract basis. But he was not doing well financially and the lockdown had been announced. Someone asked him to clean a tank in Ghazipur after he wrapped up work, and he did it because he needed the cash for his family — wife and two children. He went in, along with another daily wager, and never came out.” Radhyasham said the family was given Rs 10 lakhs by the Delhi government.

Source: Read Full Article