Why, I wonder, do city planners and development agencies not produce adaptation or mitigation programs given the vulnerabilities of the city to climate change?

Cyclone Nisarga spared Mumbai. This time. After a very stressful 24 hours for residents and leaders alike, the eye of the storm made landfall at Alibag, south of the city. Mumbai’s residents were lucky. Residents of Ratnagiri and Alibag less so. The significant human costs of this disaster will become clearer in the coming days.

Yet it is not clear if Mumbai will remain as lucky in the future. Nisarga was the first major cyclonic storm that affected Mumbai since 1948. Yet, this does not mean it will be eighty years before the next one.

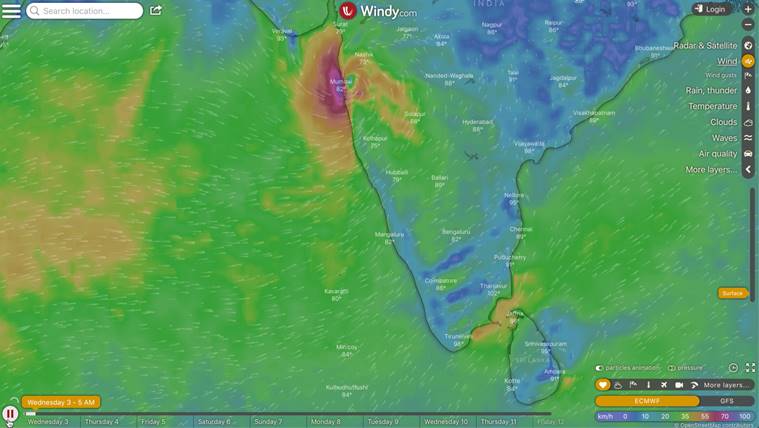

The Indian Ocean is today the fastest warming ocean in the world. In the Indian Ocean, the Arabian Sea is warming faster than the Bay of Bengal. Scientists and fishermen are already noticing the changes.

Fishers are finding their commercially valuable species vanish and new ones ending up in their nets. Scientists have noticed how cyclones, formerly rare in the Arabian Sea, are now more frequent. For much of the twentieth century, there was, on average, less than one cyclone a year in the Arabian Sea. Last year there were four.

This is more than a coincidence.

In a 2019 paper, climate scientist Adam Sobel showed that our expectations of cyclones being extremely unlikely in Mumbai are more the result of a sampling error than of fundamental cyclone climatology. Put in other words, that cyclones haven’t happened in Mumbai in recent history does not mean that they cannot happen. Less than a year later, Cyclone Nisarga proved him correct.

A different paper, published by Hiroyuki Murukami and his colleagues has not only shown that the cyclones in the Arabian Sea are more likely today, but also that this is attributable to climate change. Additionally, research by Amato Evan points to aerosolised fossil fuel emissions that now hang above the Arabian Sea as an additional factor causing more intense cyclones.

All signs point in the same direction. We can expect more intense cyclones in the Arabian Sea in the future, and with this, it is increasingly likely that some of these cyclones might hit Mumbai.

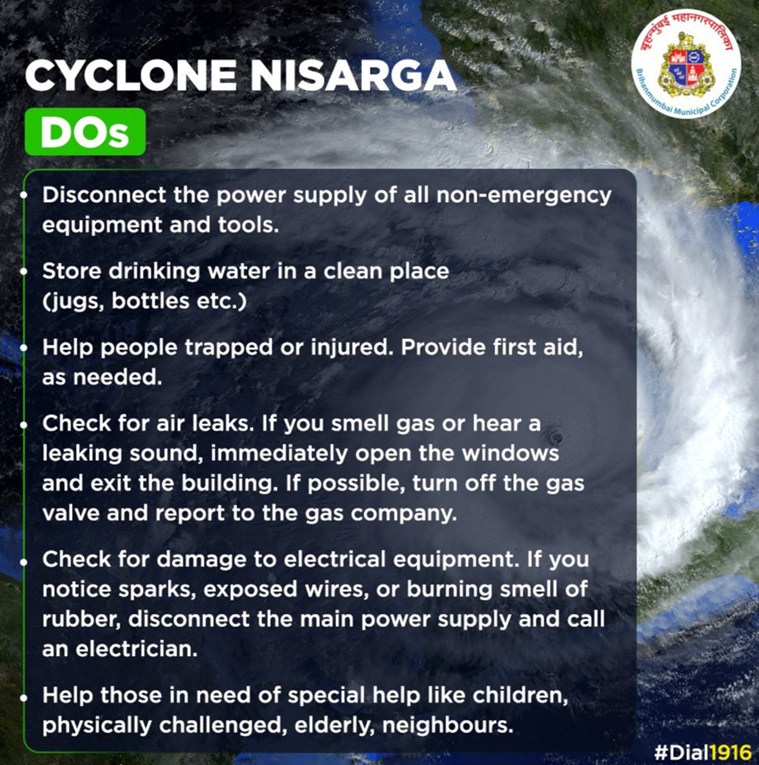

The state and city administration needs to be commended for taking quick action by moving one lakh people out of harm’s way yesterday. The next cyclone may not be as gentle as Nisarga. It may not be manageable the day before the storm.

Accordingly, the Government of Maharashtra and the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai need to proactively design urban infrastructures and public space so that Mumbai can better accommodate and withstand major cyclone and extreme weather events much before the next cyclone comes. And it may not miss Mumbai.

It may also be considerably stronger. Nisarga only appeared in Mumbai as a Category I cyclone. Yet just four days before landfall, models showed it might develop into something far worse, a Category 3 storm, with wind speeds up to 160 kmh. What might this have looked like?

In his book, The Great Derangement, Amitav Ghosh points to the many ways in which Mumbai’s location on the open sea, its construction on landfill, and its blocked water bodies make it especially vulnerable to a stronger cyclone.

For instance, on June 3 IMD officials warned that Nisarga’s storm surge might inundate nearly 3 kilometers of coastline in Pen. As Ghosh points out, the distance between Mumbai’s western and eastern coast is only 4 kilometers in the south of the city. A resulting storm surge could easily inundate vast sections of Mumbai had a slightly stronger cyclone passed north of the city.

The stronger winds of a category 3 cyclone could lift debris, loose materials, roofing materials, and throw them against its glamourous towers made of glass, imperiling rich and poor residents alike. If the city’s electricity grid collapsed, as it did in New York City after Hurricane Sandy, residents in the city’s high rises, like those in poorer sections of the city, would not have water for days.

I have recently been consumed by these spectral events since Ghosh laid them out in his book. I also continue to be puzzled by the city’s refusal to address them in a systematic and proactive way.

Why, I wonder, do city planners and development agencies not produce adaptation or mitigation programs given the vulnerabilities of the city to climate change?

It is not like they do not know the risks. A twitter post shared by the BMC a day before the cyclone foresees the cyclone disrupting energy, water and gas infrastructure.

Urban researchers Hussain Indorewala and Shweta Wag have suggested that city officials are moved more by the mundane and material profits of real estate speculation than to ensure urban sustainability. In work I have recently completed, I found planners and city officials frequently dismissing climate change inflected disasters by suggesting these are unlikely events in a distant future; that the city has more important matters to take care of.

Yesterday, Cyclone Nisarga has shown most vividly that climate change impacts are not distant, unthinkable or insignificant. They are imminent specters of catastrophic loss that hang over the city every day.

While risk modelers and scientists suggest that events like the floods of 2005 or the cyclone of 2020 are rare, this does not prevent them from happening at any time. Even if they are improbable, the next cyclone could occur in a few months or several years from now. Improbable events are happening more frequently, in Mumbai and beyond.

For example, in a recent presentation at the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities, Domenic Boyer pointed out that the city of Houston has been visited by three 500-year floods in 2 years alone! This includes Hurricane Harvey, the largest ever recorded rainfall event in the United States.

If the city remains vulnerable to such events, there is much work that needs to be done. The Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai and the Government of Maharashtra does not have the luxury to wait until COVID 19 is cured to do so, nor can it expect to have eighty years before the next climate event. It need to create an empowered and resourced task force to address these potential catastrophes tomorrow.

“Our inability to imagine catastrophe assures that the catastrophe will happen,” Amitav Ghosh pointed out in a recent interview. And absent a serious engagement with the new normal of coastal cities, the catastrophe will be worse not if, but when it happens. We just don’t know when.

Mumbai’s residents and leaders alike must demand and produce an ambitious, imaginative and just climate action plan that protects all citizens, particularly its most vulnerable. As we saw yesterday, informal residents are most exposed to extreme weather events.

Ambitious, because doing more of what has been done before simply won’t work for the city today. Reclamation and landfill have made the Mumbai of the 19th and 20th century, but they have also made the city of the 21st century vulnerable to storm surges, extreme rainfall and flooding.

Imaginative, because as storm surge expert Adam Sobel suggests, new roads, housing developments and airports that are now being built on existing wetlands and intertidal regions in Mumbai only makes the city more vulnerable to storm surge.

Award winning landscape architects and design researchers Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha agree. In their book SOAK: Rethinking Mumbai in an Estuary, they draw lessons from the Mumbai floods of 2005 to suggest the city needs to reimagine the relationship between the city and the fickle gradients of land and water across its terrain.

Towards this, they suggest a revitalisation of several city infrastructures- nalas, maidans, wetlands and indeed the sea itself- so that climate changed waters are accommodated by urban designs and infrastructure planning.

Just, because the planning design interventions need to not only involve experts but also the city’s diverse populations, including those living in the city’s informal settlements. Urban planning has seldom been a participatory democratic process anywhere in the world. It needs to become one if it is to secure the legitimacy and co-operation of the populations it seeks to govern.

Here, Mumbai’s politicians and planners would do well to learn from ongoing work by planners of other megacities like Jakarta, that also face the simultaneous challenges of informal housing, big infrastructure works, climate change and coastal inundation.

I make these suggestions not to generate a list of tasks the city needs to accomplish. I write them to speculate the beginnings of a process to carefully, urgently and justly reimagine the possibilities of Mumbai, with the specters of cyclones, storms and floods that the city and its citizens are living with today.

We need to initiate this process not because we are concerned about the future of the urban environment. We need to do so because we are concerned about the future of Mumbai itself.

Nikhil Anand is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania. His current research focuses on cities, infrastructure, seas, and climate change in Mumbai.

? The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App.

Source: Read Full Article