Like President George HW Bush, Biden respects American political traditions, and with President Barack Obama, he shares eight years of history, experiences and some Washington battle scars.

Like President Bill Clinton, Joe Biden is an empathetic extrovert with a sprawling network of friends. Like President George W. Bush, he maintains strict personal discipline (for Biden, that meant Peloton rides and protein shakes this year, to offset an ice cream habit).

Like President George H.W. Bush, he respects American political traditions, and with President Barack Obama, he shares eight years of history, experiences and some Washington battle scars.

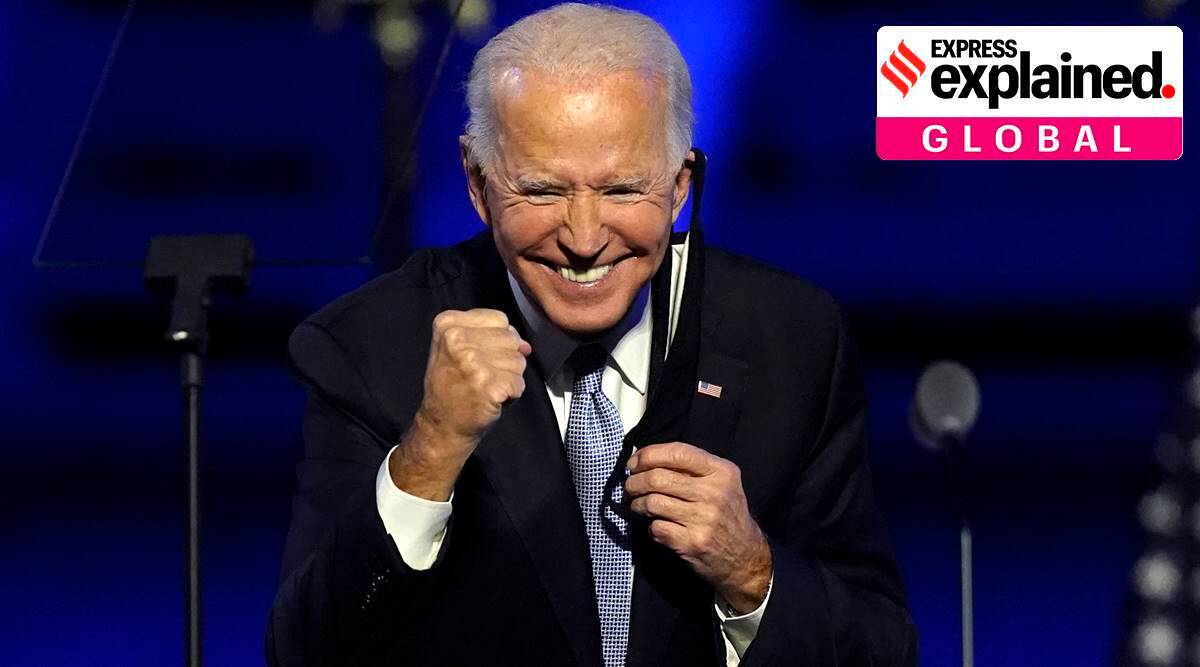

But when Biden enters the White House in January, after four turbulent years of the Trump presidency and a chaotic transition period, he will bring with him his own set of instincts.

Explained Ideas | What to expect from the Joe Biden-Kamala Harris administration

He has honed the ways he operates in Washington over 36 years as a senator and eight years as vice president. Based on his actions and attitudes throughout his most recent 18 months as a presidential candidate, here are four key elements of how Biden may approach governing come January, 48 years after he first arrived in Washington.

He consults experts, elected officials and his inner circle.

? Express Explained is now on Telegram

Biden relied this year on a blend of expert opinion and conversations with elected officials across the country as he formulated his plans to confront the extraordinary public health and economic crises at hand, offering a glimpse of the kinds of input that may influence his decision-making as president.

Explained | What obstacles stand between Joe Biden and the presidency?

When the pandemic hit, Biden’s instinct was to get on the phone.

Even though he had no power to enact policy, Biden made a point of maintaining relationships with mayors, senators and governors, calling them often and sprinkling his public remarks with references to what he had learned about their experiences. It was in keeping with the role he played as vice president, where he often was the Obama administration’s best liaison to Capitol Hill, and it reflected the respect that the longtime Delaware senator has for other elected officials.

At the same time, a core part of Biden’s message throughout the general election was that, as president, he would listen to the experts when it came to confronting the nation’s greatest challenges.

Some allies thought he did too much of that during the campaign, believing that he could have devoted more time, in person or virtually, to key battleground states rather than to the hours he spent receiving briefings on the virus and the economy even in the final days of the race.

But now he will enter the White House with an established cadre of advisers on those key subjects.

Yet for all of the expert advice Biden will have available to him from the White House, his outlook is also influenced, in broad terms, by a core inner circle of aides, advisers and a few family members — namely, his wife and his sister — who have offered counsel to him for decades.

Last week, he named Ron Klain, an operative who first started working for Biden in the 1980s, to be his chief of staff. But he has also promised to assemble a diverse administration.

“You want the steadiness, the experience and the confidence of those old hands that have been around,” former Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel said of Biden’s calculations around his administration. “But you also want new energy, new ideas, fresh faces, to bring them up. They’re the next generation. I think that’s the way Joe will look at it.”

He can be loose with deadlines.

At key inflection points throughout the campaign, Biden wanted to take in as much information as possible.

And then, he waited.

Biden ultimately is decisive, his allies argue, saying that he is not the kind of person to second-guess or to walk back a promise once he has arrived at a deal in a negotiation. But on major political and personnel decisions, at least, he has demonstrated that he cannot be rushed.

Nowhere was this clearer than during the vice-presidential search process, when Biden missed one self-imposed deadline after the next to name his running mate, before ultimately deciding on Sen. Kamala Harris. In her, he found someone he trusted to be a loyal ally, who shared his outlook on governing and who also possessed political strengths that he lacked.

That dynamic may be instructive for how his Cabinet member announcements and other personnel choices play out in coming weeks, as Biden thoroughly assesses his options and also grapples with the political constraints of a potentially Republican-controlled Senate.

People who have worked with Biden or know him personally describe him as a gut politician in some ways, but one whose instincts are shaped by conversations with close advisers and allies, by peppering aides with questions and by soliciting a range of opinions, whether from experts in a particular field or from trusted friends and supporters across the country.

“I think he truly tries to get input, get all the perspectives, understand the pros and the cons,” Rep. Debbie Dingell, D-Mich., said of his decision-making habits broadly. “He had people that gave him the perspectives of different people, and then he would make his own decision.”

Biden has suggested that he may name a handful of Cabinet member choices by around Thanksgiving — setting up an early test of whether his self-imposed deadlines are any more accurate as president-elect than they were when he was a candidate.

He’s a man of the Senate at heart — but whether the Senate likes him back is an open question.

Biden has been vice president of the United States, an elder statesman of his party and now, president-elect.

But in many ways he is, at heart, still a senator from Delaware, who sometimes slipped into the parlance of floor speeches (he referred to Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts on the debate stage last year as his “distinguished friend”) and cited Senate mentors from decades ago on the campaign trail throughout the 2020 race.

His experience in the Senate defined his political outlook — one that prizes consensus, civility and bipartisanship as essential to at least some progress — and helps explain why he will enter the White House with great respect for Congress. His insistence that he could “lower the temperature” politically was a central part of his pitch throughout the race, and he relished dismissing Democrats who called such an outlook naive.

The question is whether Biden’s views will be reciprocated by Republicans on Capitol Hill, some of whom are currently refusing to recognize the legitimacy of his election.

“He knows the Senate — these are personal friends of his, unlike other presidents that didn’t have that type of relationship,” said former Sen. John Breaux, D-La. “To an extent, Obama didn’t, either. Joe has been there over 30 years. He knows the leaders on the Republican side. I think he’s going to be reaching out to them, as well as Democratic leadership.”

When Biden declared victory last weekend, he claimed that “part of the mandate” he had received from the American people was to facilitate finding common ground.

“They want us to cooperate in their interest, and that’s the choice I’ll make,” he said. “And I’ll call on Congress, Democrats and Republicans alike, to make that choice with me.”

Whatever the response, Biden has also offered a long list of executive actions he plans to take on his first day in office.

He has a mandate to be himself.

After four years with President Donald Trump in the White House, Biden promises, in many respects, a return to the past norms and traditions that have typically defined the office.

Do not expect to see Biden use his Twitter account to fire members of his Cabinet, chime in on television news coverage or make sudden policy pronouncements. In fact, his campaign team claimed to disdain Twitter, arguing that it was a poor measure of the views of most Americans.

Do expect to see a president who embraces the traditional role of serving as consoler in chief in times of tragedy. Biden’s ability to connect with people experiencing grief is one of his most distinctive attributes as a politician, following a car accident that killed his first wife and a baby daughter in 1972, and the death of his elder son, Beau Biden, in 2015.

On Veterans Day last week, he visited the Philadelphia Korean War Memorial, and he takes care to show respect for those who serve in uniform.

Rarely did Biden grow as visibly angry on the campaign trail as when he cited Trump’s reported comments about fallen soldiers. Biden carries in his suit jacket a card that lists, among other things, the precise number of U.S. troops who have died in Iraq and Afghanistan, and he routinely ends his remarks by saying, “May God protect our troops.”

But for all of Biden’s regard for American institutions — the courts, Congress, the military — he is also a colorful figure in American politics with a vivid personality that Americans and world leaders will now see up close.

He is known for his empathy but is also capable of growing so defensive that during a testy exchange, he once appeared to call a voter “fat” (which his campaign disputed) and issued a challenge to do push-ups. He is brimming with “Bidenisms” and with assorted wisdom that he attributes to various relatives and long-dead colleagues, and is deeply proud of his Irish Catholic roots in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

“Look me over,” Biden has urged voters over the years. “If you like what you see, help out. If not, vote for the other guy.”

This time around, enough American voters liked what they saw. Now they, and the world, are about to get a much closer look.

Source: Read Full Article