The past week saw RBI, Nitin Aayog, and McKinsey Global Institute detail what India needs to do to raise growth, boost exports and reduce unemployment.

Dear Readers,

The coming week is critical for the Indian economy. Tomorrow, on August 31, the National Statistical Office under the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation will come out with the GDP estimates for the first quarter (April, May June) of the current financial year.

But before explaining what to look for in the GDP data, let me recap what happened in the week that has just ended because it will provide the context to the GDP numbers.

There were two major developments this week.

One was the publication of RBI’s annual report for 2019-20. The first thing to note is that RBI’s annual year is different from the regular financial year. For India’s central bank, the annual report of 2019-20 pertains to the period between July 1, 2019, to June 30, 2020.

This otherwise perfunctory fact is relevant this year because RBI’s year included the first quarter (April, May June) of the current financial year. This is the quarter that saw the maximum disruption of economic activity and as such everyone wanted to know what RBI made of this period.

Unfortunately, the RBI refrained from providing us with a clear number for GDP growth or contraction but it did state that “an assessment of aggregate demand during the year so far suggests that the shock to consumption is severe, and it will take quite some time to mend and regain the pre-COVID-19 momentum”.

Equally ominous were the words of Maharashtra Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray, who, while talking to the chief ministers of other non-BJP ruled states, suggested reverting to the pre-GST regime. Thackeray was responding to a GST Council meeting where the Union government expressed its inability to pay the compensation amount — roughly Rs 2.35 lakh crore — that was due to the states under the GST regime.

This suggestion could have wide-ranging ramifications for the economy if it is pursued by some of the biggest states in a serious manner.

? Express Explained is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@ieexplained) and stay updated with the latest

As different states try to recover from Covid’s impact, they need money but the current GST regime has robbed the states of the freedom to raise or lower taxes. Being asked to borrow money from the market instead of getting it from the Centre has made Thackeray question the desirability of the current GST regime. (Don’t miss from Explained: Issues in GST compensation)

There were three other important events that merit attention.

One was the launch of Niti Aayog’s Export Preparedness Index, which ranked Indian states.

The top performers were mostly coastal states such as Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Odisha but there was one landlocked state that managed to sneak into the top 5 list and it was Rajasthan.

At the other end of the spectrum were mostly landlocked and Himalayan states such as Jammu & Kashmir, Bihar and Assam. But West Bengal stood out for being ranked 22 out of the 36 states and UTs despite being a big coastal state.

A crucial takeaway from this report was the need for states to work on their unique strategy for boosting exports. This again ties in with Thackeray’s demand to have greater leeway.

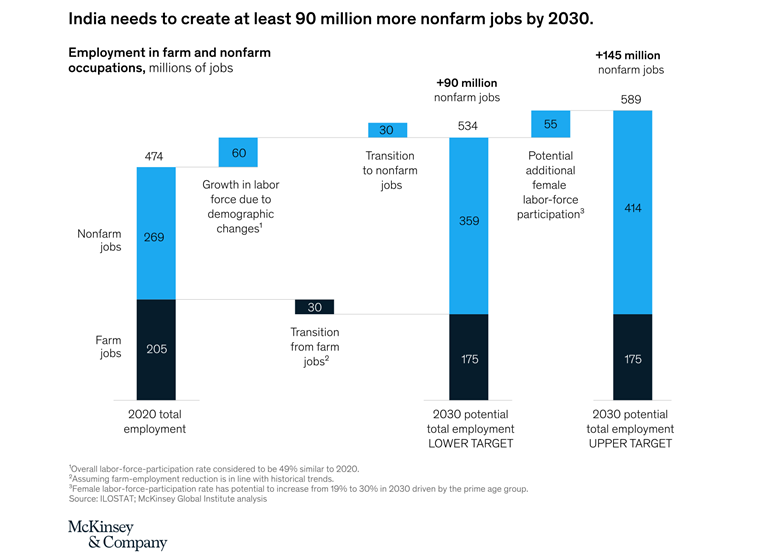

Then there was a report by McKinsey Global Institute that stated that India will have to create at least 90 million non-farm jobs over the next decade — 145 million at the upper end — and for which it would have to grow at 8 to 8.5 per cent every year (see chart below).

Lastly, on August 27, the World Bank issued a statement saying that it has ordered a “systematic review” and “internal audit” of its data and methodology used for compiling the Ease of Doing Business rankings in 2017 and 2019. The move is in response to several allegations that data was tweaked for political reasons and to favour some countries. It is important to note that India’s ranking improved from 142 in 2014 to 63 in 2019.

All of the past week’s concerns — from plummeting domestic consumption to shrinking exports to massive unemployment to question marks on India’s Ease of Doing Business rankings and GST regime — provide a useful bridge to the big event in the coming week.

Coming to GDP numbers for Q1 that will be released tomorrow.

This quarter saw the strictest lockdowns across the country and chances are it will see the sharpest fall in economic activity in a long while.

The composition of growth (or de-growth) — in other words, which sector got hit the most — will set the tone for the rest of the year. The amount and nature of the damage will point to the type and magnitude of fiscal and monetary policy efforts required to revive the Indian economy.

Most analysts expect the economy to contract sharply. But the expected magnitude of contraction differs — sometimes substantially over specific sectors of the economy.

For instance, State Bank of India’s Saumya Kanti Ghosh expects the GDP contraction to be 16%, while Madan Sabnavis of CARE Ratings expects it to be around 20% and Aditi Nayar of ICRA Ltd expect an even bigger contraction of 25%.

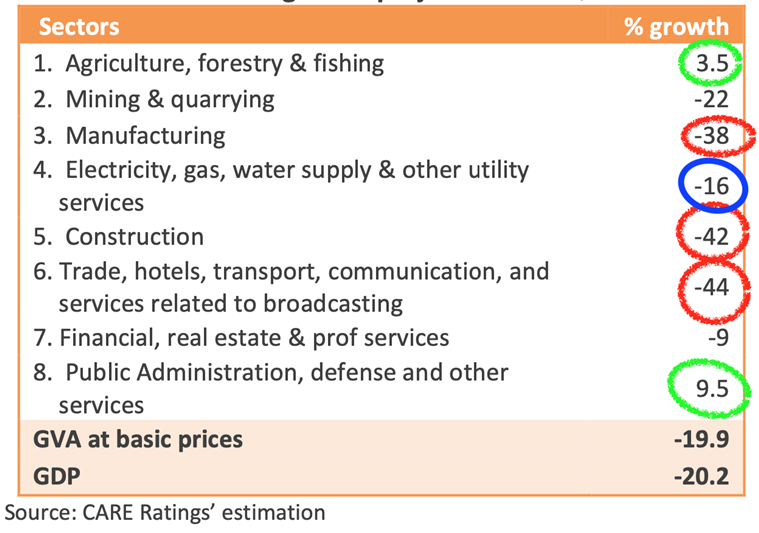

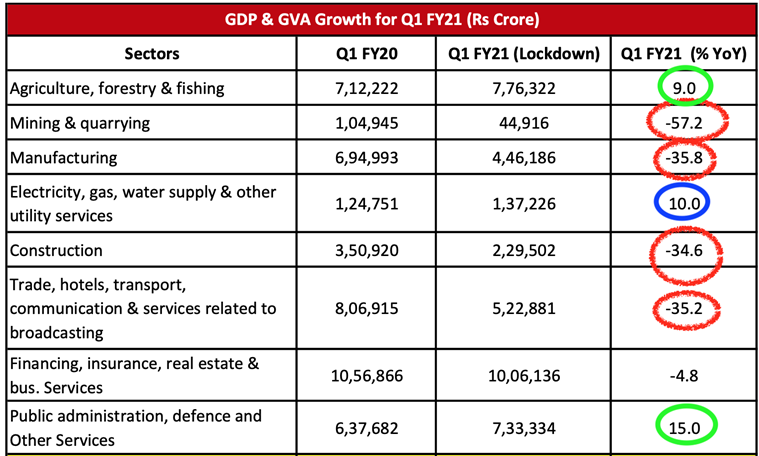

Beyond the variation in headline growth numbers, if one compares specific sectors (see charts below), one can find that two broad trends:

- that manufacturing, construction, and trade and hotels etc. are likely to have been most massively hit (highlighted in red),

- that agriculture and public administration (that is, the government) would have done pretty well (highlighted in green)

There is lesser consensus about what is likely to have happened to sectors like mining & quarrying and electricity and other utilities (highlighted in blue).

If you have been following GDP projections over the past year or so, you would have surely noticed their increasingly shortening shelf life. For instance, last year in July, when Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented the full-year Budget, she pencilled in an 8% real GDP growth. But with each passing month, the projections continued to be scaled back as the underlying economy decelerated faster than expected. Eventually, India ended the year with just 4%.

This financial year, of course, making these estimates and projections is even more difficult because Covid’s spread in India has been much worse than the government’s expectation. In the early days, the government expected no new cases after May 16. In reality, not only did India add around 5,000 new cases on May 16 but also overhauled China’s aggregate tally of over 80,000.

As India has tried to open up for work, Covid cases have surged. This week, India registered the highest single-day count of new Covid cases globally and is now the third-most afflicted country on the planet. What is most worrisome is that the rate of spread of Covid in India’s rural areas is almost double the rate of spread in urban areas.

All of this points to uncertainty about the shape of economic recovery. In this context, Monday’s data would provide the first benchmark around which future analysis can happen.

Stay safe!

Udit

? The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Explained News, download Indian Express App.

Source: Read Full Article