An exhibition on the designer showcase how he blurred the lines between art, craft and design and used block printing and calligraphy long before other Indian artists mad it fashionable to paint textiles

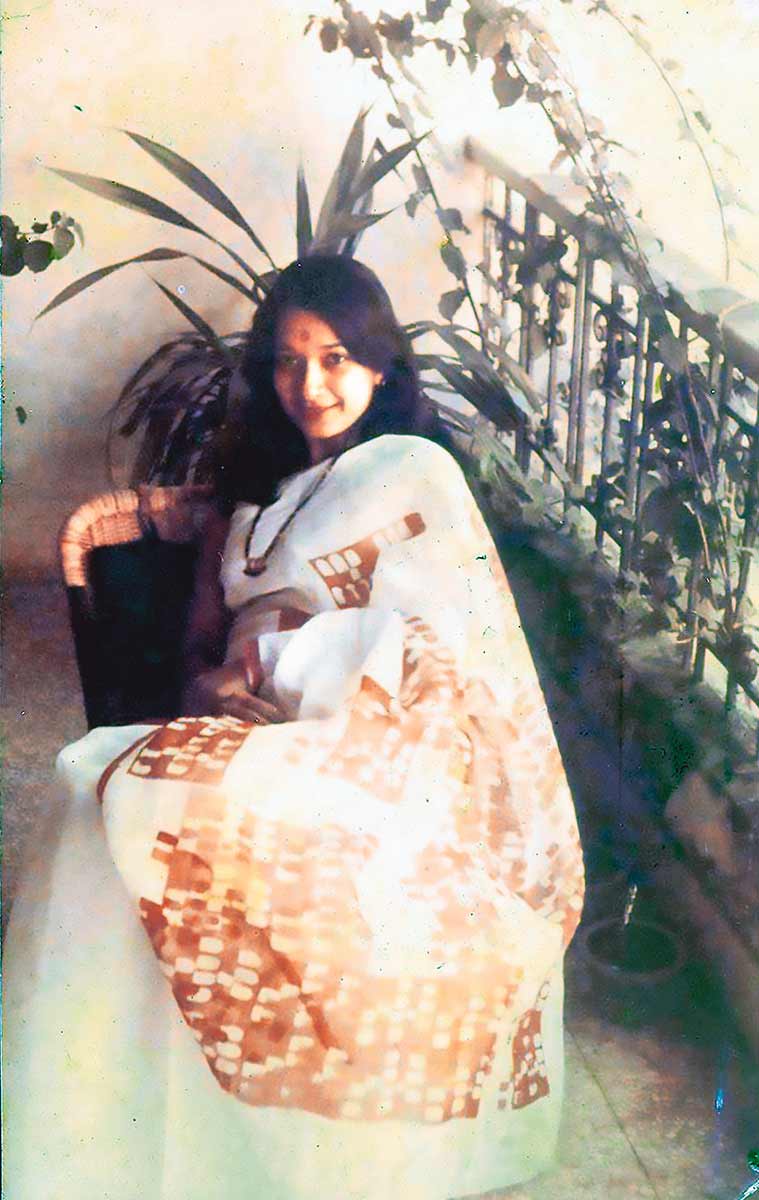

In artist Monika Correa’s sari collection, there was one with block-prints that instantly recalled Rome. It was made using a block designed by Riten Mozumdar, a close friend of Monika and her late husband, architect Charles Correa, in 1961. Mozumdar had seen the Palazzo della Civilta Italiana, also called the Square Colosseum, in Rome, and recreated its rows of arches on a block. With this design, that he called Rome by Night, Mozumdar captured an essence of Roman architecture and distilled the city’s history into a geometric pattern.

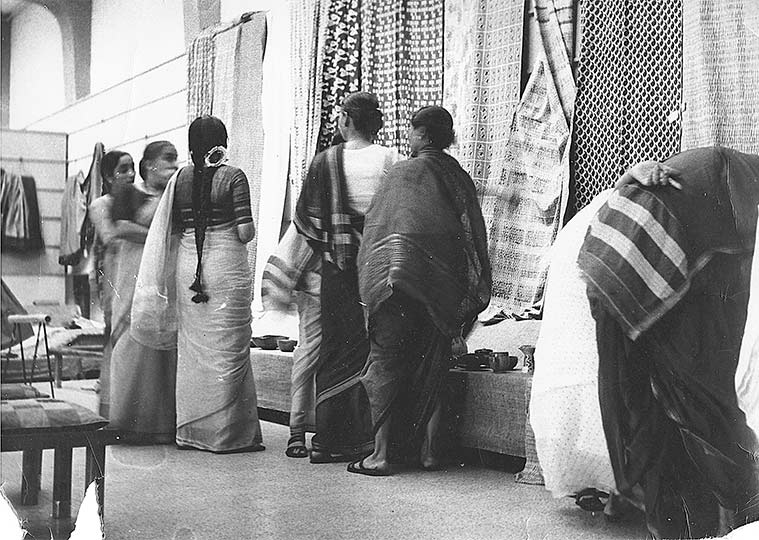

Mozumdar designed several more saris, and even a kimono, for Correa, using block-printing and calligraphy, long before other Indian artists made it fashionable to paint textiles. Geometric block-print patterns were unheard of in India before that. Correa says, “Riten was the first person to revitalise block-printing post-Independence. There were others but they were traditional, doing the same thing over and over again. Riten was experimenting.” The garment, the block, the maker and the wearer come together in “Imprint”, an ongoing mini retrospective of Mozumdar’s work at Chatterjee & Lal in Mumbai. The exhibition pays homage to this relatively understudied designer, who blurred the lines between art, craft and design.

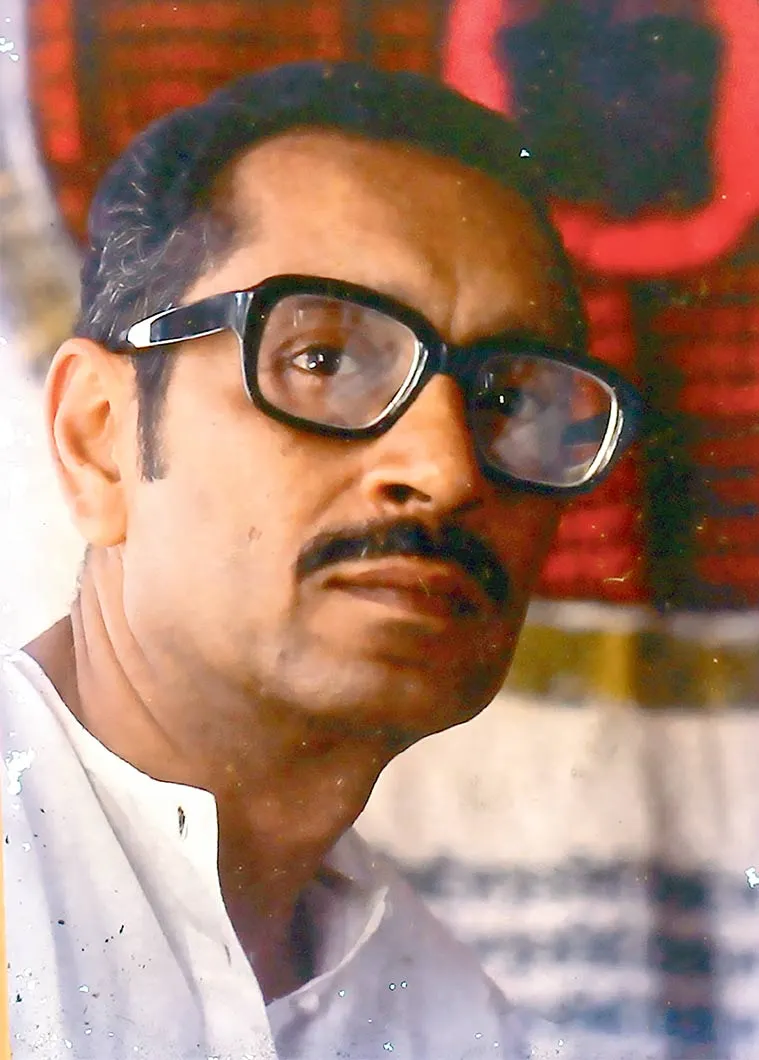

In a career spanning 40 years, Mozumdar left his mark on several things — apparel, furnishing, furniture — some of which are displayed at “Imprint”. He did all this as a colour-blind artist, able to distinguish orange from black purely by their tonal qualities. Ushmita Sahu, an artist and curator based in Santiniketan says, “Apart from his own practice as an artist, he made rugs, toys, illustrated books, woodblocks and ceramics for sale at various bodies. He also undertook large-scale interiors projects for government institutions and private ones.” Sahu, who has curated the exhibition, “Imprint”, along with gallerists Mortimer Chatterjee and Tara Lal, has been researching Mozumdar for the last three years. Chatterjee says, “During his own lifetime, Riten exhibited widely in India and in prestigious institutions around the world. However, since his death in 2006, there has been no sustained engagement with his practice and our exhibition is meant to correct this historical oversight.”

Born in 1927 in Kasur (now in Pakistan’s Punjab province), Mozumdar was the youngest of nine siblings. His father, Surendranath, a doctor, died when Mozumdar was very young, and the job of parenting fell on his mother, Prembala. Mozumdar’s eldest sister was freedom fighter Sucheta Kripalani, who became the first woman chief minister of Uttar Pradesh and of Independent India.

Mozumdar trained under pioneering artist Benode Behari Mukherjee at Santiniketan in the late 1940s, and on his mentor’s recommendation, went to Nepal, where he trained with master craftsman Kulasundar Shilakarmi. With both art and craft practices at his disposal, Mozumdar made ingenious use of block-printing and text in his works. An example of this is his use of the text from the Ram Namavali gamchhas worn by priests in Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. Mozumdar’s design removed the text from its religious context, focusing on its visual appeal, and made it secular.

Mozumdar identified himself as an artist-sculptor and approached design as an artist would, making limited edition, handcrafted pieces. In the 1950s, he worked as a textile designer with Marimekko in Helsinki, Finland, then travelled across the UK and the USA, before returning to India in 1958. The following year, he started his studio, M Print, out of a garage in Delhi.

Mozumdar entered India’s design scene at a time when a nation-building exercise was undertaken across disciplines, from constructing cities to agrarian reform. Sahu says, “Post-Independence India was imagined to be both things — tradition and Western science. About looking forward, but not forgetting your own roots. Riten was doing this, too. Like his contemporaries, he was well-travelled and had assimilated ideas of what design could be, how art was changing.” In under a decade, Mozumdar’s designs were famous and his clientele included Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Between the ’60s and the ’80s, Mozumdar was consultant to a number of public sector and private firms, notably the All India Handicrafts Board (AIHB) and the Maharashtra Small Scale Industries Development Corporation. So prolific was he that, Sahu notes, nearly everyone involved in the Indian arts and crafts sector would have encountered Mozumdar-designed objects and products in some form or other.

Indian families, too, would have cherished Mozumdar’s designs, even if they didn’t know it. A significant example of this is the work he did with textile retailer, FabIndia. Meena Chowdhury, former chairperson of FabIndia, recalls that in 1976 when the company — until then only exporting furnishings — decided to expand into retail, Mozumdar was brought in. He got carte blanche from founder, John Bissell, to design for the label. “India was moving from maroon or blue upholstery to something different. Riten’s bed and table linen hit the market sensationally. People started leaving their bedroom doors open. The linen was so spectacular that they wanted guests to know they had it,” says Chowdhury. Among his distinct designs, was the Target series, with concentric circles of orange, black and white, right in the centre of the linen. “People would often ask me if these were bedspreads or wall hangings. I’d say use them as you want to,” says Chowdhury. After Mozumdar moved to Santiniketan in 1988 to focus more on his art practice, the brand couldn’t develop more designs under his name. This year, it hopes to resurrect some of his designs, including Target, as an homage to his legacy.

Mozumdar’s designs seem as contemporary as they did decades ago. If visitors feel that the objects on display in “Imprint” are commonplace, then it speaks of Mozumdar’s role in shaping our design sensibilities. Sahu says, “His geometric designs — so simple and stark — just changed what people understood as design. Amid postcolonial chintz and paisley designs, to find a cushion cover inspired by Mondrian was new. Devoid of ornamentation and pared down to a geometric base, they retain a freshness.”

? The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Eye News, download Indian Express App.

Source: Read Full Article