In India's second village of books, a library started in memory of Mahatma Gandhi is fostering readers and building the community

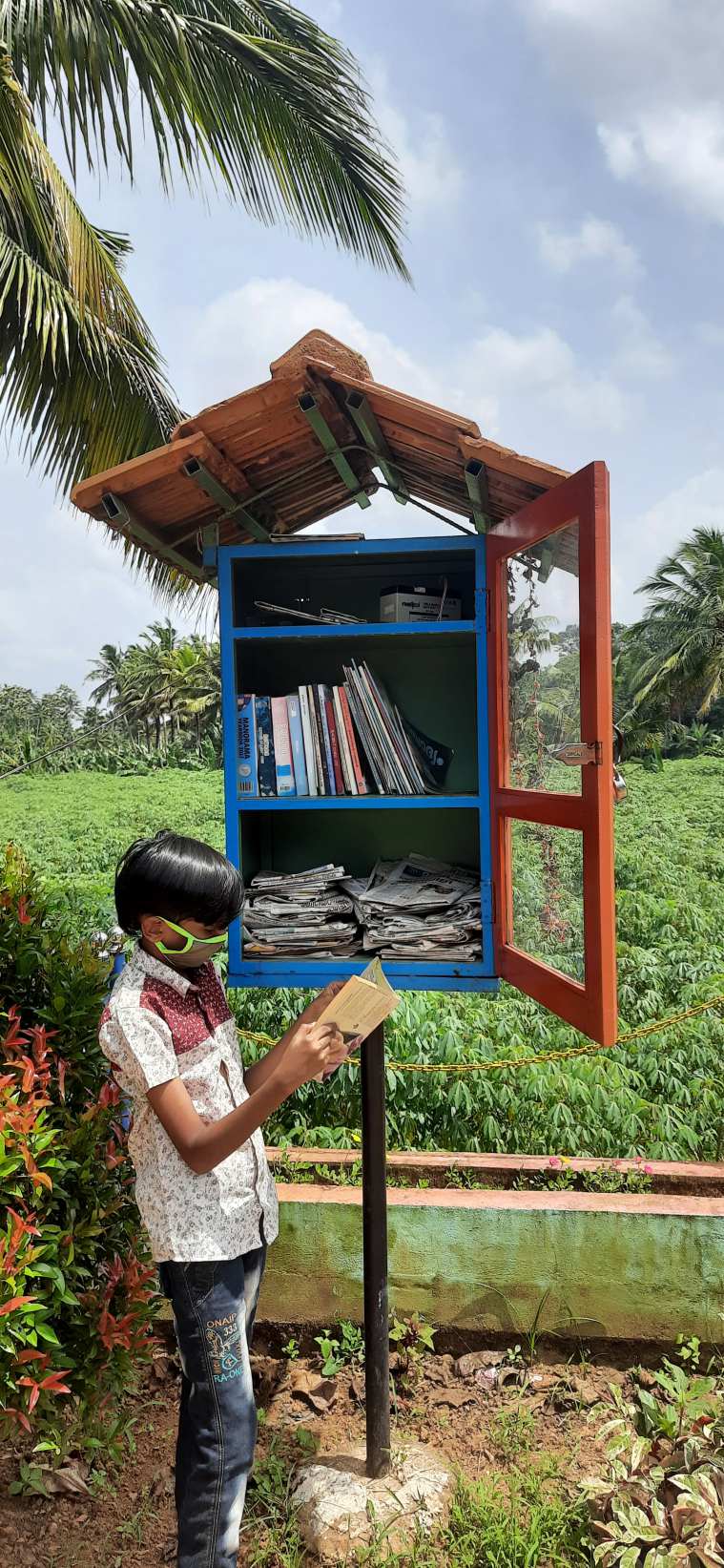

Five kilometres from the Kottarakkara town in Kollam district, in the small Kerala village, Perumkulam, a nest-like structure on a stilt by the roadside overlooks a lush tapioca farm. Schoolchildren leisurely sift through books in the box on a sultry June day. Newspapers are neatly stacked inside it, too. The otherwise bustling road, running through green fields, has been quietened by the pandemic. A board, with thermocol letters on coconut palm leaves, welcomes you at the “Pusthaka Gramam” (book village).

Last month, on National Reading Day (June 19), Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan, in a video address, formally announced it as the state’s “first book village”, after verifying with the State Library Council, and echoing the Jnanpith-winning author MT Vasudevan Nair’s “book village” declaration from last year, when he said this model should “inspire and be emulated”. Perumkulam is the second Indian village, after Maharashtra’s “Pustakanch Gaav” Bhilar in 2017, to be declared a “village of books”.

The efforts to kindle a culture of reading started way back in 1948. As the newly-independent India mourned the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, a group of young people in the Kerala village gathered a hundred books. From the room of a young man, Kuzhaykkattuveettil Krishna Pillai, began the Bapuji Smaraka Vayanasala (Bapuji Memorial Library). The library got its own building in 1957, which was damaged in 2008, rebuilt by the villagers, and renovated in 2016, says Perumkulam Rajeev, 55, the library president, associated with it since 1997. The library, which opened a branch in a neighbouring village last year, is funded by the villagers, and gets a state allowance of Rs 32,000 per annum and the librarian gets a monthly allowance of Rs 3,180. The other nearest library is the CPKP Memorial Public Library in Kottarakkara.

Today, it has around 8,000 books, which are either bought with the funds collected or sourced, including used ones, through donations. From academic books of the erstwhile Travancore princely state to autobiographies of authors like the Jnanpith-awardee Thakazhi Shivasankara Pillai, it boasts of many rare books, sourced in its initial years. Kathakali exponent Thonnakkal Peethambaran is donating his personal collection, including books he has authored, to the library this month.

On January 1, 2017, as an experiment, the patrons of Bapuji Smaraka Vayanasala with the help of the locals set up a pustaka koodu (book nest) at Radio Junction in Perumkulam, with a fear that either it would be untouched or destroyed. It’s modelled on the US’s non-profit Little Free Library movement, which allows neighbourhood book exchanges through public bookcases. The idea was well received by the 4,000-plus villagers, and the library installed 10 more such nests at bus stops, post offices and public health centres, and two more are under construction, in Perumkulam, which, among other places in India, appears on the global “map” of the Little Free Library website.

“Anyone can take books from the book nest, read and return them. We keep a register at these nests for people to enter their name and the book they take. Some people don’t return the books, but it’s fine, they read anyway,” says Vijesh Perumkulam, 43, the library’s secretary and a school teacher, adding, “Taking a cue from the initiative, Kerala’s higher-secondary education departments have installed such book nests in around 5,000 government schools across the state.”

It is the easy access to a variety of books here, which we wouldn’t have got access to otherwise and knowledge with entertainment that keeps the young readers happy. A library member for five years, Poojita Kalyani, 19, who’s pursuing a diploma in elementary education, says, “They have created a perfect ambience to read at soravarampu (a roadside adda space overlooking the farms).” Class VIII student Akshay A, 13, would have had to wait earlier for Fridays to read the children’s magazine Balarama (published every Friday by the Malayala Manorama group), says, “we read a lot now.”

“These youngsters are doing great work in Perumkulam village without expecting anything in return. They implement innovative ideas to get the younger generation to read. It is a model that is worth emulating everywhere,” says the guardian of the library, Sahitya Akademi Award-winning writer M Mukundan, 78, who’s also a recipient of France’s Chevalier of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. The patrons decided to have a literary group and formed a fans’ association for a writer, for which they chose Mukundan and seek his advice and guidance. Spearheaded by the association, 21 locals, from college students to retired teachers, are working on a novel, which will be released this year.

Living up to its name, the library puts to practise the Gandhian principle of sarvodaya (community building). It runs coaching classes to prepare students for civil services exams. It provides pension to the elderly — with severe health issues or who farm on rented land and sell locally. Its members have planted trees in the name of the village’s unsung heroes, they plant vegetables on vacant lands, from where anyone can take the produce home. And, following the 2018 floods, as part of a state initiative, it took upon itself to write lessons in notebooks for the students of Alappuzha, one of the worst-affected districts, who lost their belongings in the devastation. It will also distribute a copy of Gandhi’s autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth (1927), to every house this month. The “book village” title was given, said CM Vijayan, “in recognition of the work done by Bapuji Smaraka Vayanasala, in setting up book nests, helping students after the floods, organising farmers’ initiatives and providing IAS coaching.”

The library wishes to expand its activities and is exploring newer formats, such as “audiobooks, which are read and recorded by readers. We are planning to install book nests at the homes of underprivileged children who excel in studies,” says Vijesh. Funds, however, remain a challenge. But, as the library has catapulted into a social organisation, and more active members join, hope grows. All they ask, says Rajeev, is “to leave your politics, caste and religion outside, along with your footwear, and enter the library.”

Source: Read Full Article