Locust plague cycles – defined as a period of two or more consecutive years of widespread breeding, swarm formation and crop destruction – were a recurrent phenomenon throughout the nineteenth century and the first half of the 1900s.

There hasn’t been much “systematic research” on desert locusts in the country since the early 1990s and the current swarm invasions are a wakeup call to “restart and revive the programme”, said Trilochan Mohapatra, director-general of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR).

“A lot of basic work on their biology, breeding behaviour, development and food habits was done in the decades immediately before and after Independence, especially by stalwarts such as H.S. Pruthi, S. Pradhan and K.N. Mehrotra. Locust attacks were frequent at that time and so there was lot of research interest too. But as the problem became less severe and no smarm incursions after 1997, the focus shifted to other more regular field pests,” Mohapatra told The Sunday Express.

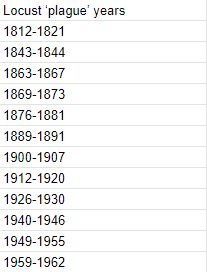

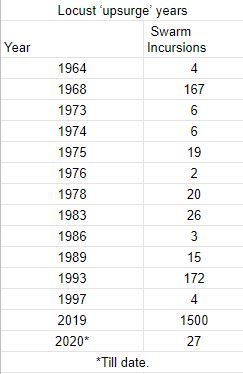

Locust plague cycles – defined as a period of two or more consecutive years of widespread breeding, swarm formation and crop destruction – were a recurrent phenomenon throughout the nineteenth century and the first half of the 1900s. The last such cycle was reported in 1959-62.

Subsequently, there have been only isolated years of ‘upsurges’; even the incursions of 1973-76 weren’t numerically large or significant enough to qualify as ‘plague’. After 1997, there were no ‘upsurges’ either – till 2019, when 1,500 swarm attacks were recorded, and the current year that has already seen 27 (see charts).

“They have come back after a long gap. So far, the damage hasn’t been much, since the only major crops in the fields now are summer moong (green gram) and early-stage cotton (in Punjab, Haryana and North Rajasthan). But we have to see what the swarms returning to Rajasthan after July for breeding will do,” Mohapatra pointed out.

The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation, on May 27, predicted “several successive waves” of locust invasions until July in Rajasthan “with eastward surges across northern India as far as Bihar and Orissa”. These movements will, however, reverse once the winds change direction along with the southwest monsoon. The swarms, basically comprising winged immature adults that are yet to lay eggs, would then come back to Rajasthan.

“They breed mostly in deserts, as the female can lay eggs only in bare sandy soils at 5-10 cm depth. She will first insert the tip of her abdomen to check if there is adequate soil moisture, then bore into the ground and deposit a batch of up to 80 eggs before filling up the hole with a protective foamy material. Such sandy soil (as against the more fertile alluvial or black cotton soils) with just enough moisture is found only in desert regions after the monsoon rains,” explained S.N. Sushil, principal scientist (agriculture entomology) at the ICAR’s Indian Institute of Sugarcane Research, Lucknow.

The presence of desert locusts in “transient mature groups” was identified in May 2019 at Pokaran teshil of Rajasthan’s Jaisalmer district. Between May 2019 and February 2020, a total area of 403,488 hectares in Rajasthan, Gujarat and Punjab was treated using 314,645 litres/kg of Malathion insecticide.

“The swarms may have come from Pakistan, but some breeding would have also taken place here last year. We need to see what happens once they breed again in our conditions over several cycles: Will they undergo genetic changes or even develop resistance to the insecticides now being sprayed? Are there other ways to control them insects, including preventing their transformation from solitary to gregarious (swarm-forming) phase?” Mohapatra pointed out.

Besides Malathion, the other chemicals approved by the Central Insecticides Board & Registration Committee for control of the desert locust are Chlorpyriphos, Deltamethrin, Lambdacyhalothrin, Fipronil, Fenvalrate and Quinalphos. Interestingly, the Union Agriculture Ministry, on May 14, issued a draft notification that listed Malathion, Chlorpyriphos, Deltamethrin and Quinalphos among 27 crop protection chemicals whose use is proposed to be banned.

The Civil Aviation Ministry, on May 21, provided conditional exemption for use of drones (remotely piloted aircraft system) by the Directorate of Plant Protection, Quarantine & Storage for aerial surveillance and spraying of anti-locust pesticides.

“The standard operating procedures for operation of drones, including dosage and concentration of the insecticides to be applied, will be finalised in the coming week,” an official stated. Being relatively light-weight and battery-operated, the pesticides sprayed through unmanned aerial vehicles would require higher active ingredient concentration and lower water volumes than that in the normally-used formulations, he added.

? The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest India News, download Indian Express App.

Source: Read Full Article