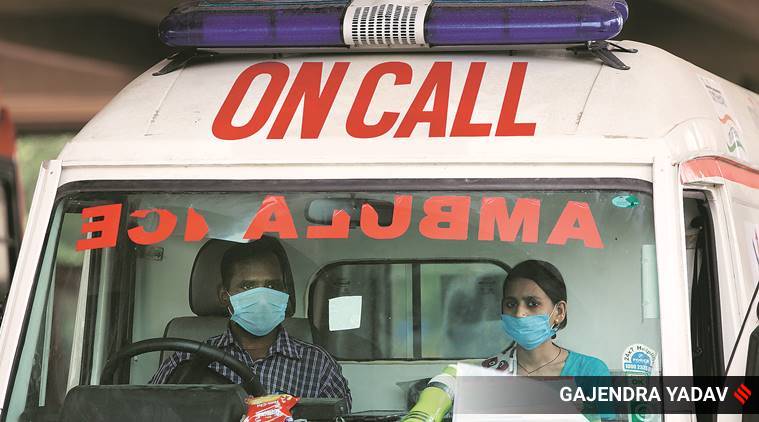

In the hierarchy of frontline workers, ambulance staff rank among the lowest. As one of them dies in Tamil Nadu, The Indian Express spends a day with two on duty in Delhi, India’s worst-hit city.

As the focus in coronavirus fight shifts to preventing deaths, the government has recognised time taken to reach hospital and the call refusal rate of ambulances as key aspects in clinical management of patients. But, in the hierarchy of frontline workers, ambulance staff rank among the lowest. As one of them dies in Tamil Nadu, The Indian Express spends a day with two on duty in Delhi, India’s worst-hit city.

—

He first unfastens the face shield, then peels off the hazmat suit — a shade small for his 5’7” feet frame — and finally, almost tears open the shoe covers. Thick beads of sweat dot ‘pilot’ Tej Bahadur’s forehead; the back of his shirt is wet. The paramedic who is part of his ambulance team, Roshni, 24, slips out of her suit awkwardly, conscious of the eyes on her at the Covid hospital where they are parked. The kurta she is wearing underneath is damp, and she adjusts her dupatta so as to cover it.

Discarding the Personal Protective Equipment in a bin, the two take in deep breaths. Their third assignment for the day, transferring a Covid-19 pregnant woman from Delhi’s Lal Bahadur Shastri (LBS) Hospital to Guru Teg Bahadur (GTB) Hospital, 10 km away, took a refreshingly short 60-odd minutes.

Response time critical

AS INDIA’S Covid-19 caseload crosses the one million mark, getting patients to hospitals on time assumes an even more critical role in reducing fatalities. While in Delhi and Maharashtra the ambulance response time is now below 30 minutes, Telangana and Karnataka, which have seen a surge more recently, the response time (45 minutes to an hour) must improve.

“The hospital agreed to admit the patient and Roshni could complete the paperwork in time. There has been no guarantee of either in the past three months,” says Bahadur.

The 43-year-old is an ambulance driver with the Delhi government’s Centralised Accident & Trauma Services (CATS). As the numbers surge and focus shifts to preventing deaths, ambulances are more crucial than ever in the coronavirus fight. In end June, at a meeting the Centre held with states, the time taken for patients to reach the hospital and the call refusal rate of ambulances were recognised as key aspects in keeping fatality rates low.

With Delhi the worst-hit city in the country, and India at third highest in Covid-19 caseload in the world, the Central and state governments have been stressing on increasing ambulance strength. The Supreme Court, Delhi High Court and NHRC have all taken up the matter, responding to cases, reported from across the country, of patients collapsing while waiting for ambulances.

With 17,407 active cases, 3,729 of them in hospital, as of July 16, Delhi currently has approximately 602 ambulances. CATS has nine Advanced Life Support (ALS) ambulances, 142 Basic Support Ambulances (BLS) and 109 Patient Transport Ambulances (PTA). Besides, 154 ambulances have been converted to dedicated Covid-19 ambulances, while about 200 Ola and Uber cabs have been roped in to ferry non-critical patients. Private hospitals and institutes have their own ambulances.

The Centre has assured 650 more ambulances in Delhi, while the state government has declared plans to double the number.

Bahadur pilots a BLS, which is equipped with a stretcher, two five-litre oxygen cylinders, a first-aid kit, medicines for stabilising heart attack patients, and kits to carry out deliveries. While his is not a Covid ambulance, Bahadur says he has been attending only coronavirus calls for the past few months.

Bahadur is aware of the case of Ganesh, a 22-year-old ambulance technician who died in distant Tirupur, Tamil Nadu, on June 24, soon after he tested Covid-positive. He is also aware that, among all the frontline staff helping tackle coronavirus, the ambulance drivers are among the least celebrated; Ganesh’s death lost almost as a footnote.

Bahadur has been tested seven times— each time after his PPE kit tore or he came in direct contact with a suspected case. The tests are organised by his employer, GVK-EMRI, the private firm that holds the contract for CATS ambulances in Delhi. GVK-EMRI was also Ganesh’s employer.

“Fortunately I have tested negative,” Bahadur says, adding, “The Tirupur guy must have kept a poor diet, or been careless.”

So, apart from PPE (he usually has four-eight sets in his ambulance at all times), Bahadur takes several precautions of own, like breathing in mustard oil fumes before leaving home, drinking giloy juice, having only boiled water, that he carries with him, and using “lots and lots” of sanitiser.

Roshni banks on “kadha and lemon water for breakfast”. She started working as a paramedic only a month ago and her duties include “patient evaluation, emergency care, safe transportation, and paperwork”.

While she admits she never expected to find herself in the middle of a pandemic, the 24-year-old adds, “There are quite a few women paramedics on ambulance duty now.”

However, she adds, “I have never been tested.”

***

Around noon on a hot, muggy Wednesday, Bahadur and Roshni are sitting on a rug with two fellow ‘pilots’ and paramedics at their ‘base’ — a footpath, under the Vinod Nagar Metro Station in East Delhi.

Bahadur uses the break to place request for supplies at a CATS call centre over the tablet provided to him by CATS.

Earlier, they would take their breaks in a room at LBS Hospital. “But we had to vacate it as we were accused of leaving behind PPE suits. That’s not true. Because of the heat, we take off the suit the moment we drop a patient. We don’t wait to get to the base.”

A driver with the East Delhi Deputy Commissioner’s Office earlier, Bahadur joined GVK EMRI last year. He is on call 12 hours a day, with working hours stretching beyond. In a month, there is a fortnight each of night and day shifts, and both Bahadur and Roshni get two days off a week.

With response time of ambulances under scrutiny, Bahadur says, “It can take 10 minutes to an hour, depending on distance and traffic.” After every assignment, they drive the ambulance back to the base for fumigation, which takes an hour. With seven-eight Covid cases coming his way in a day, this means he ends up driving at above 100 km/hr, with traffic rising post-lockdown.

Bahadur says he left his previous job to give his brother, a kidney patient, more time. “Now I schedule his dialysis when I am off work.”

To support his family of 10, including three children who go to private schools, Bahadur does other small jobs on his off days, like AC repair or bike and car servicing. “My salary of Rs 17,000 per month is not enough.”

Roshni worked as nursing staff at a private hospital earlier, but her family was uncomfortable with her late working hours. “I always wanted to do something in the medical field. So I completed a six-month Emergency Medical Technician course last year and applied for job as a paramedic,” she says.

With her father disabled, her salary of Rs 17,000 every month helps run the seven-member household.

***

It’s been a busy morning, with Bahadur and Roshni having transported first a 35-year-old Covid-19 male patient from Vinod Nagar to LBS Hospital and then a pregnant 19-year-old to Jeevan Jyoti Hospital in Dilshad Garden. The Covid case didn’t need any medical aid, but they had to carry the 19-year-old on a stretcher.

Smiles Bahadur, “We were lucky she lived on the ground floor. A few days ago, I had to carry a 90-kg man along with an oxygen cylinder to the ambulance down from the fourth floor. His wife made us park the ambulance far from the house because she didn’t want the neighbours to know. It took nearly four hours to complete the job.”

Despite her petite frame, Roshni often helps Bahadur carry patients.

There are other problems as well they are facing for the first time. “Recently, a Covid-positive couple being taken to GTB fought that they didn’t want to go to a government hospital,” Roshni says.

They attend to three kinds of calls — from government hospitals, from the District Surveillance Officer (DSO) assigned to monitor coronavirus cases, and from individuals. While patients may choose to go to private hospitals, often the DSO or a hospital tells them where to take the patient.

Bahadur talks of the initial months, April-May, and driving around with a 45-year-old Covid-19 patient between hospitals, which refused to take him. As coronavirus patients are on their own, without relatives, often he and Roshni have to intervene. “The patient’s oxygen levels ran low, but losing his cool, he got off and started walking. I ran after him and called the DSO to find a bed for him,” he says.

Another time, Bahadur says, a hospital demanded that a TB patient show a ‘Covid-free’ certificate. “Where would he get that from?” he says. “I took him back home.”

Things are more settled in the Capital now, Bahadur adds. “Earlier, we did not know what to do if a hospital refused admission. There were fights with security, nurses, hours spent in PPEs. So we collected the numbers of DSOs of our zones. We now call them up directly.”

A source in CATS said while vehicle numbers are “almost sufficient” now, getting patients admitted remains a challenge. “We have to often call up the CMO (Chief Medical Officer) or the CDMO (Chief District Medical Officer).”

T V S K Reddy, Vice-President at GVK EMRI, said, “We have brought in vehicles from Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Kerala. We now have over 240 ambulances on the road in Delhi on Covid duty. We have also hired more drivers, from 600 earlier to 780 now. Our average response time has reduced from 55 minutes to less than 30 minutes.”

A senior Delhi government official on Covid duty said they had set up a dedicated war room to ensure that “every patient with escalating symptoms was able to reach hospital in time”. “In the first week of May, CATS ambulances catered to an average of 576 calls a day with patient handover time of 4 hours 28 minutes per Covid call. In the first week of July, the CATS service catered to an average of 890 calls per day with patient handover time of 2 hours 49 minute per Covid call,” the official said.

What worries Bahadur more than anything is the stigma attached to coronavirus. “When I was little, we were so poor, we would go days without meals. I need to earn a living, that’s all I know… I at least have a job in these times…” he says, and so back in his neighbourhood, a majority of the people believe he still does his old job. “I chose the East Zone, so that they don’t come to know.”

While Bahadur rides his motorcycle to the government hospital where the ambulance is parked when not on call, Roshni now uses an autorickshaw to get there from her home in Mayur Vihar in East Delhi. One night, she says, as Bahadur was dropping her home after their shift, neighbours confronted her. “They refused to let me get out, said bacteria fael jayega (You will spread the bacteria).”

Her family is supportive and has been taking all precautions to avoid direct contact with her. “We have a three-storey house. I stay in the single room on the ground floor and have hardly met anyone in a month. We use hot water to bathe and drink warm water.”

***

On the other end of the spectrum are private ambulance drivers such as Raju, 40, with little safety net. Till two years ago, he used to drive tourists to Kedarnath. He became an ambulance driver, he says, as it ensured a guaranteed salary and now works for a private ambulance service running out of Jamia Nagar for Rs 15,000 a month.

That’s barely enough to support his wife and four children, the youngest 10, Raju says. Now, he is apprehensive about the people, including dead, he has been transporting, often to other states. “I suspect many of them are coronavirus positive … I wear mask, gloves, use sanitiser, what else can I do?”

Recently, after he had ferried a family to Uttar Pradesh from Delhi’s Safdarjung Hospital, he found himself stuck at a quarantine centre near Gorakhpur for two weeks. “Some security people told me a person I had dropped was Covid-positive.”

Philosophical, Raju adds, “When death has to come, it will. Near my home in Okhla, people turned their backs on a Covid-19 patient, but I went and offered him food. We can’t be scared.”

***

Around 2.30 pm at the base, Bahadur receives a call to transfer a Covid-19 positive pregnant woman from LBS to GTB Hospital. Both Roshni and he avoid eating while on duty, mainly due to santisation concerns. They don gloves, figure out the case details and get on the ambulance.

At LBS Hospital, Bahadur steps out of the ambulance to don the PPE. Roshni changes inside the van. “Ladies ke liye tough hai (it’s tough for women). I wear the suit over my clothes but it still feels like I am changing in public,” she says.

As the Covid patient arrives, the two get her details from a nurse, reconfirming that the GTB Hospital will admit her. “Otherwise, we will spend hours arguing,” says Roshni.

As they set off, already sweating profusely after a few minutes in the July humidity, Bahadur notes, “We have been getting a lot of pregnant patients.” The traffic is light, and they cover the 10-km distance in 20 minutes.

Having ensured that the patient has collected everything she is carrying, Roshni escorts her to the Covid ward. She gets in touch with the nursing officer and completes the paperwork before handing over the patient.

Bahadur regrets having left his bottle of boiled water back at the ‘base’. “I will drink water once I get back,” he says, relieved to see Roshni returning soon. “Paperwork jaldi ho gaya,” she tells Bahadur, as the two rush to remove their PPE.

There are other assignments that day, one of them entailing a trip to a government hospital in Tughlakabad, 20 km away, which takes so long that the patient leaves for Lok Nayak Hospital on own. “He hired a private service. Such patients complain later that the ambulance didn’t arrive,” Bahadur says.

It’s around 10.30 pm that he gets home, finding his children already asleep. Ready to pass out, he says, “Fortunately, I don’t have to take my brother to hospital today.”

Reaching home around the same time, Roshni says her biggest regret is not cuddling up to her niece. A quick meeting with her mother later, she will settle for the night. She never had time for habits such as watching movies, the 24-year-old says, and is grateful for this now. “I just want to sleep.”

? The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest India News, download Indian Express App.

Source: Read Full Article