UK abolished the offence in 2009 but the seeds sown in colonial India to stifle free speech still bear fruit here. Before India turns 75, it must junk this law

Written by Abir Phukan

Bal Gangadhar Tilak was charged thrice and convicted twice by the British for sedition within a span of 20 years for publishing a few articles in the Marathi newspaper Kesari. He was unequivocally critical of various aspects of the British administration in India and minced no words in condemning repressive measures of the British Raj and demanding Swarajya. For his first conviction, he was sentenced to 18 months’ rigorous imprisonment and for his second conviction, he was sentenced to six years’ transportation, which he served in a prison in Mandalay. During his second trial, Tilak submitted before the jury, comprising seven Europeans and two Indians, that it was time that the press in India be treated at par with the press in England.

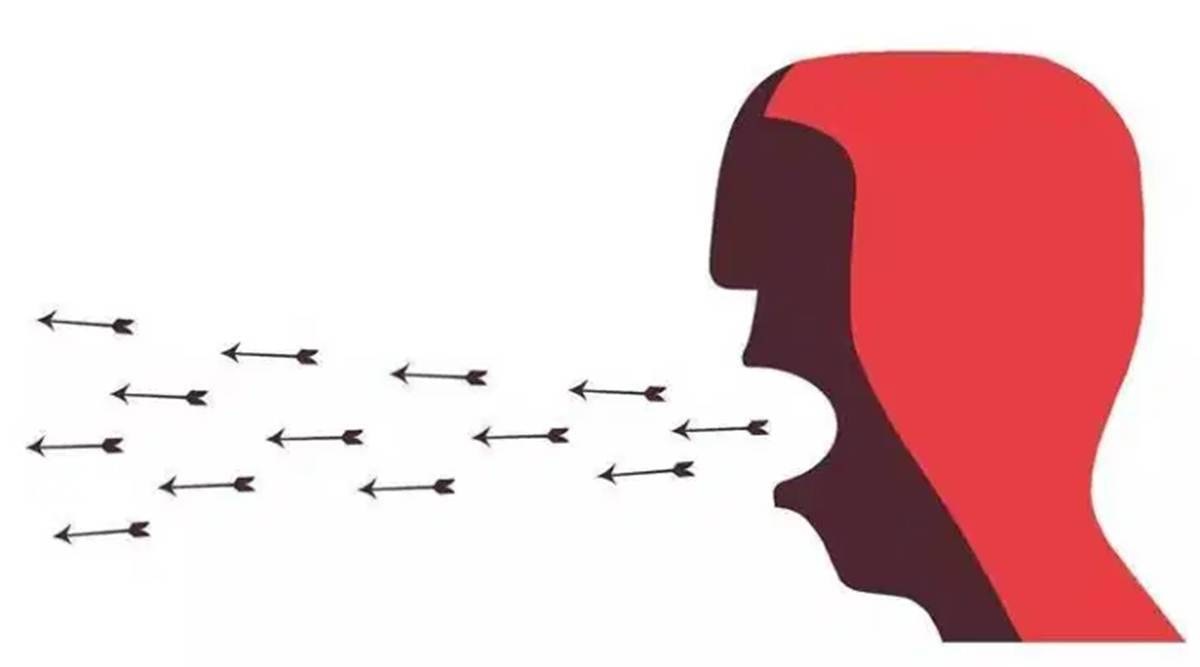

After 100 years, in an ironic turn of events, the United Kingdom abolished the offence of sedition in 2009 after it had become obsolete for many years, whereas India is just beginning to ponder whether Section 124 A in its current form ought to be retained. While repealing sedition, the Parliamentary Undersecretary of State at the Ministry of Justice of UK, Claire Ward said that “Sedition and seditious and defamatory libel are arcane offences – from a bygone era when freedom of expression wasn’t seen as the right it is today…” Unfortunately, the seeds sown in colonial India to stifle free speech still bear fruit today as independent India is about to commence its 75th year. Any critical views of the administration are often nipped in the bud by registration of First Information Reports (FIRs).

Recently, the Supreme Court quashed an FIR registered against a senior journalist, the recipient of Padma Shri and many other awards. He was accused of sedition and other offences while reporting on the unfolding situation after the imposition of the first lockdown. In his talk show, the journalist highlighted the need for adequate testing facilities, PPE suits, N95 masks and ventilators. He emphasised that disruption of supply chains on account of the lockdown could result in scarcity of food.

Exercising powers under Article 32 of the Constitution, the Court found no merit in the prosecution’s case that false information or rumours were being spread by the journalist. The Supreme Court stated that he was within his rights as a journalist to address “issues of great concern so that adequate attention could be bestowed to the prevailing problems”. The judgment also rejected the argument that movement of migrant workers had begun as a result of the spread of incorrect information in the talk show.

In another recent case, the Supreme Court quashed a criminal complaint against a senior journalist from Shillong. Her offence was that in a Facebook post, she condemned an assault by a few tribal boys on non-tribals in Shillong. She appealed to the government and the police to take up the matter with the seriousness that it deserves. She questioned why non-tribals should continue to live in perpetual fear in Meghalaya.

Rejecting her prayer for quashing the FIR registered against her, the High Court observed that her Facebook post sought to arouse feelings of enmity and hatred between two communities and prima facie made out an offence under section 153A. The Supreme Court reversed the view of the high court and observed that the Facebook post only expresses the author’s agony and was directed against the apathy shown by the state and the police.

Sri Lankan journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge wrote an editorial for his newspaper, the Sunday Leader, three days before he was killed by unidentified attackers. His piece was published posthumously by Sunday Leader as well as The Indian Express in January 2009. According to Wickrematunge, it was his job to be more critical of the government than of the opposition because “there is no point in bowling to the fielding side”. He wrote, “The free media serve as a mirror in which the public can see itself, sans mascara and styling gel. Sometimes the image you see in that mirror is not a pleasant one. But while you may grumble in the privacy of your armchair, the journalists who hold the mirror up to you do so publicly and at great risk to themselves.”

While time and again, the judiciary has stepped in to strike down unreasonable restraint on the freedom of speech and expression, we seem to be stuck at the crossroads. How else do you explain the continuing investigations and prosecutions under Section 66A of the Information and Technology Act, 2000, that was struck down by the Supreme Court seven years ago? Commenting on the wide reach of the section, which could catch within its net “virtually any opinion on any subject”, the court had observed that “if it is to withstand the test of constitutionality, the chilling effect on free speech would be total.”

The anguish generated by increasing prosecutions of journalists was, perhaps, best summed up when a Supreme Court Bench recently wondered if sedition cases have been filed against news channels which showed dead bodies being thrown in a river during the second wave of the pandemic. A batch of petitions challenging the constitutionality of section 124 A are likely to come up for hearing soon before the Supreme Court. It would be a fitting tribute to the Constituent Assembly of India, which firmly opposed sedition as a restriction to freedom of speech and expression, if provisions like 124A which brazenly stand in the way of a free and independent press are wiped out of our statutes before India turns 75.

The writer is a Delhi-based advocate and founding partner at KMNP LAW

Source: Read Full Article