Neerja Chowdhury writes: It aims to protect Brand Modi, distance the government from Covid criticism and reach out to OBCs ahead of UP poll.

The Prime Minister has tried to re-seize the political initiative with his Wednesday reshuffle of the council of ministers. Since April, he has been on the back foot. When the second Covid-19 wave hit the country, many died reportedly from oxygen shortages and a general lack of government preparedness. Losing West Bengal also did not help, particularly when the Prime Minister and Home Minister had campaigned intensively in the state.

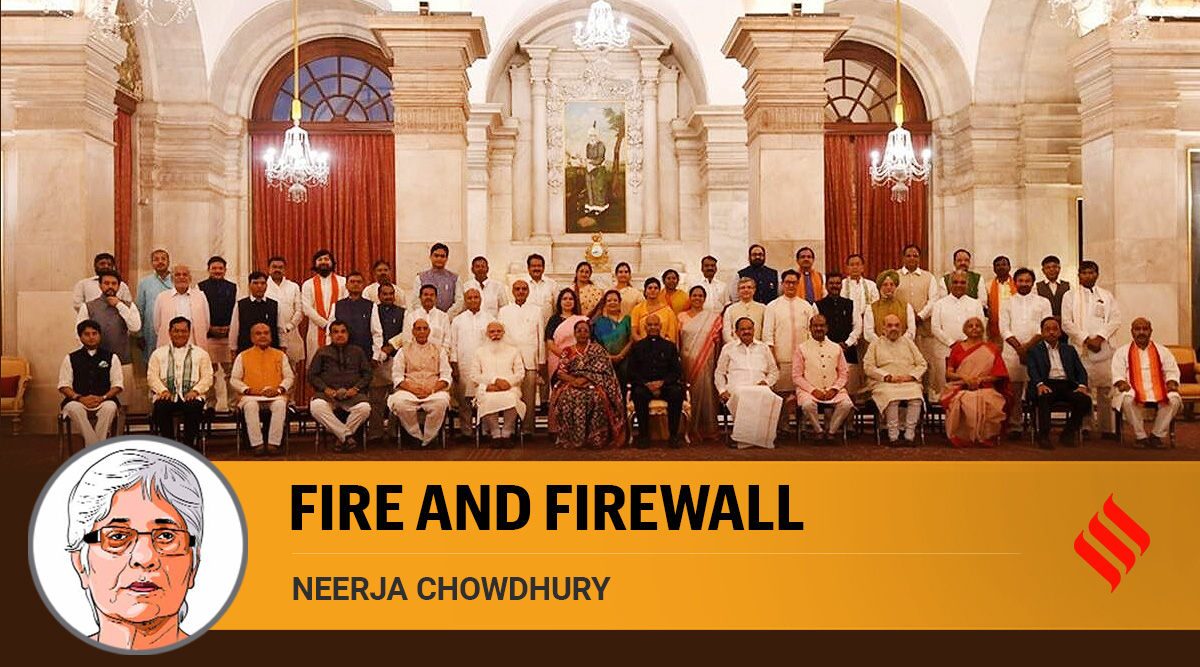

The reshuffle has turned out to be more than an exercise to fill vacancies. Few had believed that Narendra Modi could axe a dozen ministers, for it would amount to admitting that all had not been well. With his tough leader image, Modi is not given to undoing his decisions. But that is precisely what he did on Wednesday. He sacked 12 ministers, particularly those at the head of ministries, which had brought criticism to the government in the last year and more.

There was the inept handling of the second Covid wave, and Union health minister Harsh Vardhan has had to go. There was mass migration last year, with lakhs trudging back to their villages, something India will take a long time to live down, and labour minister Santosh Gangwar was shown the door. Education minister Ramesh Pokhriyal was axed for the confusion that prevails in the education sector.

The sacking of Ravi Shankar Prasad and Prakash Javadekar, who were fielded most frequently to defend the government, came as a greater surprise. As Communications, Electronics and Information Technology Minister, Ravi Shankar Prasad’s handling of the impasse with Twitter and the increased criticism of Modi on the microblogging site, may have cost Prasad his job. It was social media that built Modi’s image in the first place, helping him to bypass conventional media. Javadekar, too, may have been found wanting for his inability to prevent criticism of the government in the media, domestic and foreign.

It is hardly a secret that the government is driven by the Prime Minister’s Office, not by individual ministers. The ministers could not have done what they did without the clearance of the PMO. Ministers today essentially play the role of implementers. It is possible that the roadmap suggested by the PMO was not operationalised to the satisfaction of the PM.

Given the unhappiness at the way the second Covid wave was handled, some heads had to roll. Else, the anger would have singed the Prime Minister further. According to surveys, his ratings had fallen after April. Even middle-class families, once solidly behind him, were becoming disenchanted. Almost every family had lost someone they knew, or knew of, to Covid.

The PM has signalled that he wants a purposeful government. That there has to be accountability in a parliamentary democracy. And that the new entrants have to shape up. Protecting Brand Modi was an important part of the exercise. By holding only ministers responsible, the PM has made a distinction between those individuals and the Modi sarkar.

Modi has his eye on the forthcoming state elections in 2022 and 2023 — and the general elections in 2024, and beyond. The PM has tried to represent every state of India, in some cases sub-regions in states, as well as different castes, particularly OBCs, Dalits and tribals, in his ministry. For the first time, there are 11 women ministers in the government. Women have emerged as an important vote bank, and bailed out Nitish Kumar in the recent Bihar elections and Himanta Biswa Sarma in Assam.

While every state is important, it is Uttar Pradesh that is critical. In 2014, had UP not elected 71 BJP MPs, it would have been a hung Parliament, and Modi’s political trajectory might have been very different. If the party loses ground in 2022, it will lose steam for 2024. With seven new inductees from the state, the number of ministers from UP has gone up to 15 — in other words, one-fifth of the total strength, which is supposed to send its own message.

The BJP is especially reaching out to the OBCs again, whose support in UP is vital for it to ward off the challenge from the Samajwadi Party-RLD combine. The “mandalisation” of the BJP is taking place; the party can no longer be called a Brahmin-Bania outfit. There are now 27 OBC ministers out of 77 in the Modi ministry. Modi is the first OBC to sit on the prime minister’s chair. In 2014, his OBC credentials were talked about in undertones. Now, he may decide to play the OBC card more openly.

Undoubtedly, satta mein shirkat (participation in power), as former Prime Minister VP Singh used to say, has its own logic. But will it offset the resentment that has been brewing in UP with the loss of life and livelihoods, and the growing anger amongst farmers, particularly in Western UP?

When Modi came to power in 2014, the Atal -Advani era in BJP came to a close. In 2019, the phase dominated by “Gen X leaders” also came to an end. Arun Jaitley, Sushma Swaraj, Ananth Kumar passed away. Venkaiah Naidu became the vice-president. Now, there are only a handful of leaders left in government from the “old BJP” such as Rajnath Singh and Nitin Gadkari. The latter has lost one of the ministries—MSMEs—which was under him.

The PM is now putting in place his own team. It is a young ministry, the average age being 58 years. Modi is known to favour former bureaucrats, professionals and experts more than old-school professional politicians. The new whizkid is Wharton-educated Ashwini Vaishnaw, who has been given railways and IT to turn around. There are experienced hands in Jyotiraditya Scindia and Sarbananda Sonowal. The question is this: Will they, and others, get the space to generate new ideas, innovate, take decisions and be given the freedom to make mistakes, so as to be able to deliver?

The new ministry is rich in symbolism. But with petrol prices crossing the Rs 100/litre mark, 230 million reportedly under the poverty line, millions of jobs reportedly lost in the organised sector alone since the pandemic began, and a third Covid wave a possibility, people will need more than symbolism to disregard their suffering.

This column first appeared in the print edition on July 9, 2021 under the title ‘Fire and firewall’.

The writer is a senior journalist.

Source: Read Full Article