Stand-up comedians in India prepare for a lot of things — awkward silences or an audience that is not in on the joke. But, over the last decade, amid increasing instances of fragile egos and easily-hurt sentiments, an FIR has also come to be one of them

Stand-up comedian Munawar Faruqui’s post on social media from the last fortnight goes something like this:

I come from Two Indias

1947

2014 #FreedomOfSpeech

Faruqui’s joke, while alluding to the controversial statements made by actor Kangana Ranaut (who claimed that India actually got its freedom in 2014 when the Narendra Modi-led government came to power, and not in 1947), is modelled along the lines of yet another controversy — stand-up comedian Vir Das’ monologue, I Come from Two Indias.

On November 15, Das, 42, posted a YouTube video that presented observations on India, some intended to expose the nation’s hypocrisies and ironies, at a sold-out show at the Kennedy Centre, Washington, US. “I come from an India where we take pride in being vegetarians and yet run over the farmers who grow our vegetables” was part of this piece as were remarks on Bollywood, cricket, and the PMCares fund.

The viral clip from the show lasted all of six minutes. As of this week, at least two persons associated with the BJP in Mumbai and Delhi have lodged police complaints against Das; the Madhya Pradesh home minister Narottam Mishra, also from the BJP, has disallowed Das’ future performances in the state; and INC spokesperson Abhishek Singhvi tweeted that Das had generalised “the evils of a few individuals and vilified the nation as a whole in front of the world”.

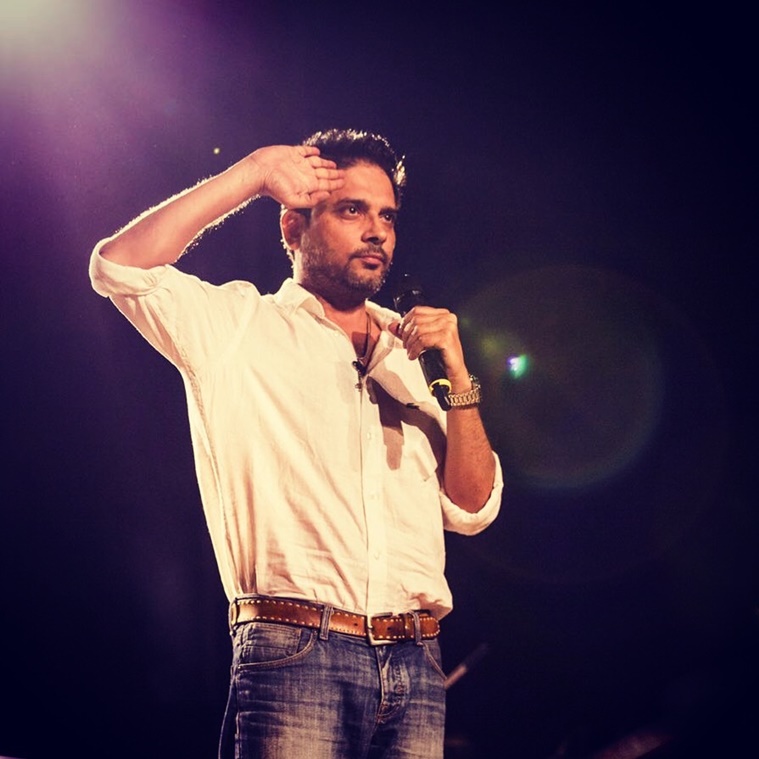

Das is the latest in a long line of stand-up comedians and satirists who have been intimidated or arrested in recent years for hurting religious or national sentiments. In January this year, Faruqui, 28, was arrested at a venue in Indore even before he could perform his set, Dongri to Nowhere. The arrest came after a complaint from the son of a BJP MLA, who accused Faruqui of making jokes on Hindu deities and home minister Amit Shah. The alleged jokes, however, were not made at the venue, as per eyewitness accounts reported in news and research website Article 14. Faruqui spent over a month in jail.

“Someone or the other is targeted everyday on the internet now,” says Faruqui, who started off with open mics in 2018 and has risen to nearly 1.5 million subscribers on YouTube recently. Earlier this month, organisers cancelled his events in Mumbai and Goa following threats of physical, emotional and financial harm. Faruqui says, “You say what you think is right and what you stand by. There are lots of people who follow you on public platforms. You have to take the responsibility that comes along with it.”

Other comics have also faced backlash on grounds of “hurting” sentiments, religious or otherwise. By now, it’s clear that political humorists come from two Indias — one, where you are thrown in jail for a joke and another, where you joke about your time in jail. In a country where biker groups and physiotherapists are offended by jokes, nationalists can’t be far behind.Comedians prepare for a whole lot of things — awkward silences or an audience that is not in on the joke — but is an FIR also among them?

There have been several warnings in recent years about the shrinking space for freedom of expression in India, such as a steadily falling rank in the World Press Freedom Index. Speaking on this subject also has become a challenge, with observers often labelled as dissenters. Several well-known comedians chose not to comment for this story or retracted their comments, citing various reasons.

“We have artists like Kunal Kamra and Varun Grover, who have developed a strong voice in the space… But they know that it still comes with potential legal complications, threats of violence, people showing up at venues to shut down shows or vandalise the place, and even getting tossed in jail, as we saw earlier this year. Younger comedians are extra cautious. Few are willing to open themselves up to the increasing risks involved,” says Ravina Rawal, editor, DeadAnt Co, an online publication that tracks India’s comedy culture.

Stand-up comedy in India is currently a well-defined genre, distinct from film comedy and YouTubers, but just over a decade old. From around 2017 onwards, Rawal recounts, a lot of comedians were venturing into the space of political satire, and it looked like it could evolve into a solid sub-genre with many exciting voices. Aisi Taisi Democracy (ATD), Das’s News on the Loose, AIB’s On-Air With AIB, were among them. Audiences also got used to laughing at things they haven’t had the nerve to say out loud themselves. “But things started getting messy quickly. I think it comes from the realisation that comedians now have staggering reach and the potential for impact — on young voters, for instance — and that’s making everyone nervous,” she says.

When Mumbai-based comic Azeem Banatwalla, 32, calls himself a “traditional Muslim man”, the audience scoffs, knowing well that the comedian is by no means one. In July 2020, Banatwalla suspended his Twitter account and later issued an apology for tweets from many years ago. He stated that he was subjected to the “vilest of Islamophobic abuse”. Over email, Banatwalla tells us that he has spent most of his career making jokes about the culture he was born and brought up in. There are jokes about the stereotype of Muslims being terrorists, but that seems forgotten because the focus is always on perceived slights against “Hindu culture”. People with political agendas attack smaller comics and venues — soft targets, essentially — to showcase themselves to their political peers, he adds. Banatwalla says that it is easy for a lot of comics, especially the newer ones, to joke about the right wing. “It’s an easy laugh because, let’s face it, nobody in the government exactly covers themselves in glory,” he says.

Banatwalla’s apology was one of the many posted online around the same time in 2020. Rohan Joshi, Sahil Shah and Sapan Verma (also members of East India Company), and Aadar Malik were among them. The spate of apologies rose in the aftermath of a joke on misinformation surrounding a proposed Shivaji statue in the Arabian Sea. Agrima Joshua, the stand-up comedian who had made the joke, was threatened by a Hindu activist with legal action if found guilty of insulting a state and national icon; she was viciously trolled online and subjected to rape threats.

Practising for the last five years, Joshua, 31, has often made digs on Indian politics, but doesn’t identify herself as a political humorist. In her first and only video, “UP is the Texas of India”, Joshua jokes about life in Uttar Pradesh, as both a citizen and a Christian. She unlisted the video that also mentions the Shivaji statue after threats to her life. “If you profile these men attacking comedians, women and artistes, you’ll learn they are the same people who made an issue out of (Pakistani actor) Fawad Khan performing in India. There’s a lot to unpack here — fragile masculinity and the need to protect women or our culture, along with the panic over interfaith and inter-caste relationships,” she says.

Stand-up comedian Shyam Rangeela, 26, says that sometimes his family asks him to “go easy” on his content. Earlier this year, when Rangeela was visiting his village in Sri Ganganagar in Rajasthan, he got into a discussion with his friends regarding the petrol price crossing the Rs 100 mark. “As I expressed my concern, most of them said Modiji har kaam soch samajh kar kartein hain (The PM gives a lot of thought to all his decisions). The hike in fuel prices must be to deal with the pandemic-induced slump in the economy,” recalls Rangeela, who rose to fame mimicking the Prime Minister. It gave him an idea for a new act. He immediately searched for the nearest petrol pump and got verbal permission from the owner and agreed to share the video with him, he says. The next day, however, moments after he had uploaded the two-minute parody video in the Prime Minister’s voice on his YouTube channel, he got a call from the owner, informing him that he was filing an FIR against him.

Rangeela uploaded another video, ‘Petrolwala crime’, explaining why he decided to not take down the February 16 act. It has got close to 30 lakh views. “If I had taken down the video, then it would have been better to just give up doing comedy. Even I support PM Modi, but that does not mean that I cannot disagree with him,” says Rangeela, but admits that decisions such as these have come at a cost. In 2017, the comedian was allegedly told on a reality TV show, on which he was a contestant, to not mimic either Modi or Rahul Gandhi. He was eventually eliminated from it.

Political satirist and member of ATD, Sanjay Rajoura, 49, says his scripts are tailored for his audiences and he relies mostly on everyday observations for inspiration. “Today there is an audience for stand-up comedy even in small towns, where people respond to jokes on issues related to daily life. In urban centres, people are largely ignorant,” he smiles, adding, “But jokes on government’s criticism work in all centres. Everyone relates to it.”

Rajoura and ATD had an FIR registered against them following a show in Shillong in 2019 titled Science ki honour killing, but, over the years, he says, only “those who identify with our content come to our shows” and so the backlash has reduced. “Say if there are 2,000 people in the audience, then only 4-5 people will disagree with us… We also don’t upload most of our shows, only small clips,” he says.

Many believe that political humorists are inherently anti-establishment. Karthik Kumar, who runs Evam Standup Tamasha in Chennai, says that comedy takes pot-shots at the establishment, that they wouldn’t take labels like right-wing or left. “We really don’t care who’s in power. We are the ones who call the emperor naked and if we are not allowed to do that, there is a great loss…” There are comedians whose material aren’t anti-establishment, as much as just pointing out little absurdities in political leadership or the social fabric. It may be a small part of a larger narrative on, say relationships and sex, but attacks against them are focused on that stray line or two.

In 2017, 34-year-old comedian Sourav Ghosh’s joke on how airports in Mumbai were named after Shivaji became the basis for an attack from Maharashtra Navnirman Sena’s (MNS) supporters. When Ghosh responded to comments on his video, MNS supporters grew more enraged and Ghosh was forced to issue a statement. The incident came in the way of getting shows in the city, too. “I was never the kind of comedian who had sold-out shows. But even the controversy did not help me sell tickets,” he says with a laugh. Last year, Ghosh left Mumbai for good due to pandemic-related reasons. He opened his own comedy venue, Topcat Retired Comedy Club in Kolkata, with the intention of building the scene in his city. “Comedians have to find a way that works for them because attackers will always find a way. Currently, the whole comedy scene in India is a tad bit defensive,” he says.

In Mumbai, The Habitat, currently the most popular venue for comedy events, is no stranger to controversies. Joshua’s attackers had vandalised the venue when she had performed her piece; a mob had gathered outside the venue in retaliation to Ghosh’s show, and Balraj Singh Ghai, its owner, was asked by the police to shut the venue for a week. Ghai says, “Venues are brick-and-mortar spaces. When a comic is hard to find, the venue is an easier target.” As of this year, Ghai has started a light screening of scripts being performed at the venue and is more vigilant about what parts of the show make it to digital platforms.

In one of Faruqui’s videos, Ghost Story, The Habitat’s logo gleams, dented in a corner from the time the attackers came to the venue in July 2020. “I think we are going to let that be there. It’s like Leopold Cafe has its bullet marks [from the 26/11 terror attacks]. Let people know what we are dealing with,” says Ghai.

Source: Read Full Article