Ghar Ka Pata, in essence, documents Madhulika’s shifting status from a tourist to an immigrant. But apart from being a heart-rending personal account, it provides human faces to an exodus whose severity keeps coming in the way of recovery.

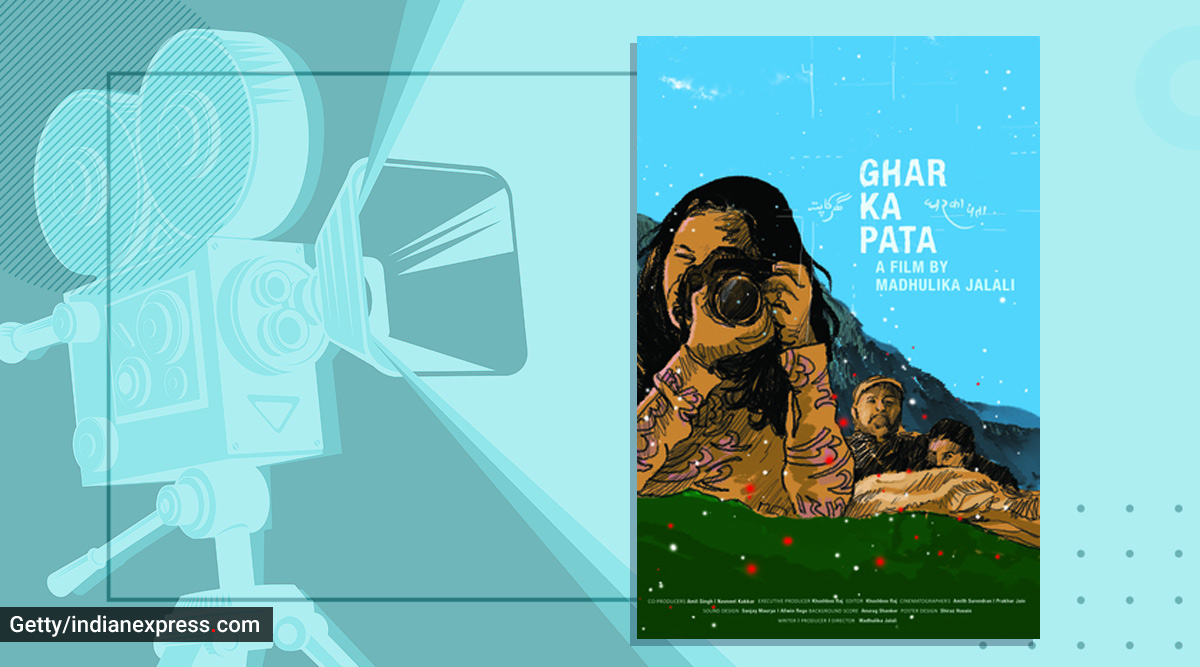

The urge to come back home is so primal that in spite of its unique specificities it is universal. The incentive is so potent that the desire sustains itself. Think of the Greek hero Odysseus who left Ithaca to fight the ten-year long Trojan War and then braved every obstacle for another decade to reach home. Or the Roman poet Ovid who when banished from Rome by Augustus in 8AD, ruefully declared “Exilium mors est” (Exile is death). One can argue that if the destination of life is death, then in all barrenness its purpose is to build a home and return to it. This seems so natural that by moving away one earns an identity solely in relation to their distance from home — an immigrant, expat or exiled. This continuous marching towards home then is to preserve what belongs exclusively to someone. Madhulika Jalali, a Kashmir Pandit woman who along with her family was compelled to flee the valley during the 1989 insurgency, initiates this return after losing everything. And in her documentary, aptly titled Ghar Ka Pata — withholding both a sense of revelation and longing—she chronicles this journey.

The documentary opens with a 2014 footage when the family was taking a trip to Kashmir. Sitting in a car with Madhulika holding the camera they resembled a group of tourists. The intervening 24 years had changed their relationship with the place. But the underlying familiarity is distilled in a lovely instance when her father freely admits to the driver that his heart flutters being in the place. Madhulika holds on to this throwaway sentiment, sensing both his rare abandon and practised caution. Even though she discloses later that he did not show her their old house, the trip she told indinaexpress.com was a turning point. “I felt a strong pull that left me unsettled.”

This ‘pull’ stemmed from witnessing belongingness first-hand and not experiencing it. To change that, she went to Kashmir two years later but could not locate her home. This inability eventually made her realise that she did not remember the house too well and her memories of it were in fact borrowed. This loss stuck to her and followed her around as she changed three cities and six houses. Madhulika began piecing together information about the house to know what she was mourning for. She interviewed relatives and immediate family members, pored through old family albums and finally went to the valley with her elder sister.

ALSO READ | Dhummas: The Gujarati short film is a compelling tale of familial abuse

Ghar Ka Pata, in essence, documents Madhulika’s shifting status from a tourist to an immigrant. But apart from being a heart-rending personal account, it provides human faces to an exodus whose severity keeps coming in the way of recovery. In this regard, Jalali’s work is acutely personal and private, much like the loss of home itself. The most devastating bits constitute recollections of the night they left to never come back again. The suddenness is shuddering — her mother shares she washed clothes before leaving, thinking they would need it later— but the uncertainty is crippling. Her sisters, Urvashi and Neetu, both older than Madhulika but considerably younger when it happened present an unalloyed picture of the crisis, inserting their narratives and immediate fears. There is a poignant moment — amusing only in retrospect — when one of them says the first thing she took while leaving was her report card even when ration cards were left behind.

What makes the documentary an empathetic portrayal of homecoming is its familiarity with loss, in its acknowledgement that everyone loses in their own way. There is brutality in it but also humanity. This is illustrated in the final moments when Madhulika reaches their hometown in Rainawari, Srinagar with elder sister Urvashi in 2018 and encounters people and places they had left behind–the grocery store at the corner, the building where the sisters would go for tuitions. Much like Urvashi, they too have memories of the sisters from that time. But the real crushing moment arrives when they meet their erstwhile Muslim neighbour and both break into sobs over a common loss. At that instant it ceases to matter that communal factors instigated the mass exodus. Looking at them hugging each other as the elderly woman swears her life for them, one understands loss constitutes of leaving and being left behind. That notwithstanding what causes it, it is always secular.

“When you lose a home in such circumstances, you don’t lose just the physical entity but the very foundation of your existence,” Madhulika told indianexpress.com over an email. The entirety of her documentary is then that– seek the foundation of her existence, retrace her roots so that she can finally be rooted, and examine the complexity of identity to understand if it constitutes of where we come from or where we are going.

And yet this arduous journey started from knowing all was lost, the visit to Srinagar merely confirming it. One can argue closure as a compelling reason but she rules it out as a possibility in this lifetime. The question then is why did she go all the way to find a home knowing there was none or what did she expect to find in a place she did not remember too well? How do you build a foundation of your existence from vacant land? This thread of futility runs deeper as Article 370 was revoked during editing the documentary, rendering her decades-long identity struggle “invalid”.

To presume she did it to belong would be an overreach. To suppose she did it to know that she belonged, however, would be closer to the truth. For is not that what homecoming is about anyway? Not to come home but to know there was a home to come back to?

(Ghar Ka Pata is playing at Dharamshala International Film Festival)

Source: Read Full Article