A new book narrates the journey of Indian music to the West through the life of Lakshmi Shankar, India’s first female vocalist to be nominated for a Grammy.

In the album Dancing in the Light (World Village, 2008), 83-year-old Hindustani classical singer Lakshmi Shankar can be heard navigating the depths of Hindustani classical music through five pieces — a khayal in raag Puryadhanashree, two thumris and two Meera bhajans. The voice is mature, quite dazzling at straight notes, hitting them with a rousing elan in rhythmic precision. Sometimes, the same voice is slightly insipid and also a reminder of other, sometimes better, renditions. But Dancing in the Night has to its credit what many don’t — a Grammy nomination in 2009 for the Best World Music Album (Traditional).

That year, South African band Ladysmith Black Mambazo took the golden gramophone home, but Shankar, too, was suddenly a name people were curious about. Hers was the first Grammy nomination for an Indian female vocalist. After the announcement, the name found mention in music circles and newspapers, even as it drew a blank among the masses. And that bothered New York-based Kavita Das, 44, who knew Shankar as a family friend since childhood, and wondered why an artiste of her stature was not as celebrated.

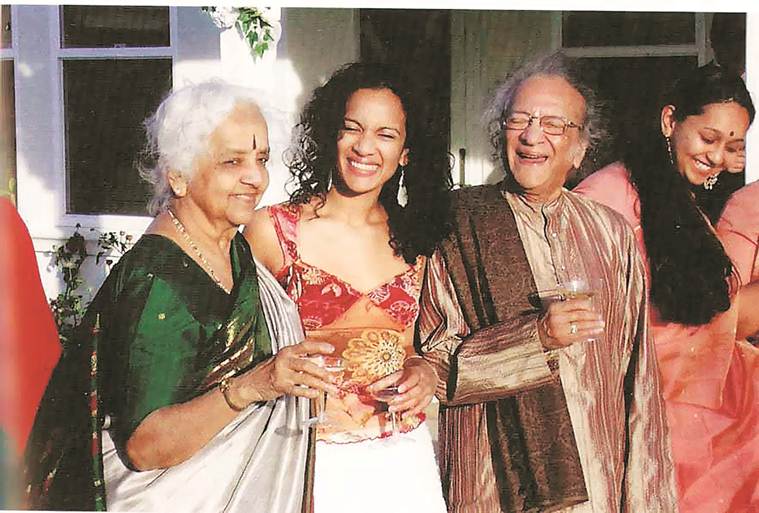

“As a woman of colour in the US, I was always amazed at how she did what she did,” says Das, whose new book Poignant Song: The Life and Music of Lakshmi Shankar (Harper Collins, Rs 399) chronicles the life and times of an artiste who lived her life across continents, was a cultural ambassador, toured extensively with Pt Ravi Shankar and George Harrison, reinvented herself from being a dancer to a singer, and garnered a Grammy nomination, but the world wasn’t talking. So Das decided to.

A couple of years after the Grammy nomination, Das — whose parents, both doctors in New York, organised Lakshmi’s concerts for many years — visited the artiste in Los Angeles. By this time, Das was working with social change and racial justice for New York-based Race Forward. During half a dozen meetings she had with Lakshmi, the artiste spoke of her life and its contours. The passing of sitar maestro and Lakshmi’s brother-in-law, Pt Ravi Shankar, in 2011, led Das to understand that “these figures don’t live forever and it was significant to chronicle”. So, even after Lakshmi passed away in 2013, she continued to go into the depths of a relatively unsung artiste.

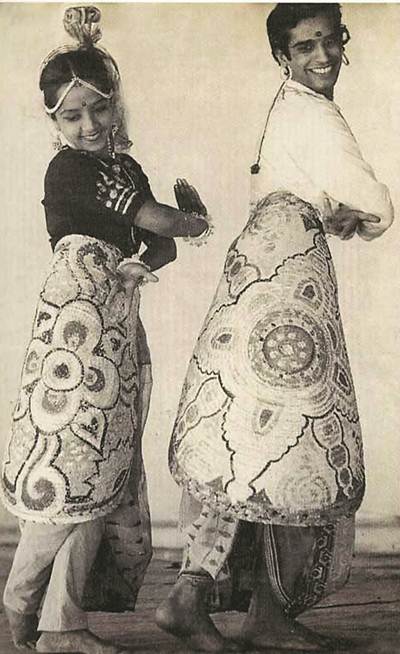

Born into a Gandhian Tamil family in 1926, Lakshmi began dancing when most girls didn’t. Her mother Visalakshi, also associated with the Indian freedom movement along with her husband, was in thrall of the then young Bharatanatyam artiste, Balasaraswati, whose concerts she would attend in Chennai. She decided to send her daughter to Balasaraswati’s guru — the iconic Kandappan Pillai. Lakshmi then auditioned for Uday Shankar’s new dance academy in Almora. “If it was unspeakable for a South Indian Brahmin girl to dance, it was inconceivable for her to move to the other side of the country to join a dance troupe,” writes Das in the book.

It’s in the foothills of the Himalayas, that Lakshmi studied the Uday Shankar style — the merger of various classical styles into a cohesive whole. At 13, she was learning alongside famed ballerina Anna Pavlova, sisters Uzra and Zohra Sehgal, and Amala Shankar. When Lakshmi was 15, Uday sent a marriage proposal for his younger brother Rajendra Shankar, 21 years her senior, and the troupe’s manager. A simple ceremony later, Lakshmi was married into the family.

For the next two years, she travelled with the troupe, starred in a series of productions until the western donors stopped funding the centre due to the Second World War and it was shut down. That’s when Lakshmi — along with her husband and son — moved to Mumbai to pursue opportunities in the film industry. Soon, Pt Ravi Shankar also joined them with wife Annapurna Devi and son Shubhendra. Lakshmi starred in the Tamil Talkies film, Bhakta Tulsidas (1947) but couldn’t find more work. So she pursued opportunities as a playback singer and found work with composer Madan Mohan and sang for her brother-in-law in KA Abbas’s Dharti Ke Lal and Chetan Anand’s Neecha Nagar.

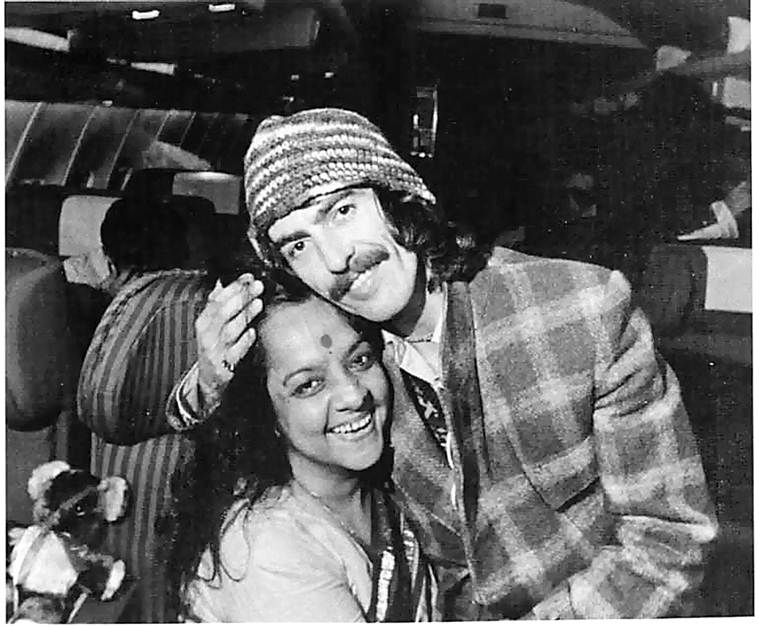

After a bout of illness, she could not dance anymore. Mohan had once introduced her to Ut Rahmat Ali Khan of Patiala gharana, and thus a Tamil-speaking Bharatanatyam dancer and Carnatic musician began learning Hindustani music. Soon, there were a few concerts here and there. In 1974, she collaborated with Ravi and the famed Beatle — George Harrison — for a Hindustani pop song, I am missing you, as the finale on a tour in Canada. This is when the West heard a female Hindustani classical vocalist on a global stage. By this time, MS Subbulakshmi had already performed at the UN and was doing classical concerts in the US. But Harrison’s involvement gave this tour and Lakshmi a different level of exposure. “This book is for anyone who is curious about this era, this moment in time when Indian music made its way to other parts of the world. Also, it is significant to understand the barriers that Lakshmi transcended,” says Das.

But more than that Grammy that registered her presence in 2009, for Lakshmi, it was giving voice to one of Mahatma Gandhi’s favourite bhajans, Vaishnav jan toh, for Richard Attenburgh’s Gandhi that remained special. “To have met Gandhi as a child and then to sing for the film was not just nationally significant, it was personally significant for Lakshmi,” says Das, whose research also involved studying Shankar’s autobiography Ragamala and Peter Lavizolli’s The Dawn of Indian Music. Lakshmi’s niece Anoushka Shankar has written the book’s foreword. A large section is based on Das’ conversations with Lakshmi, while some have come from conversations with Lakshmi’s granddaughter Gingger Shankar (violinist L Subramaniam and Viji Subramaniam’s daughter).

“She managed to stay authentic and yet was open to collaborations. That was unique,” says Das. Lakshmi died in 2013, at 87, a life quite extraordinary in a world that will perhaps know her better in the years to come.

Source: Read Full Article