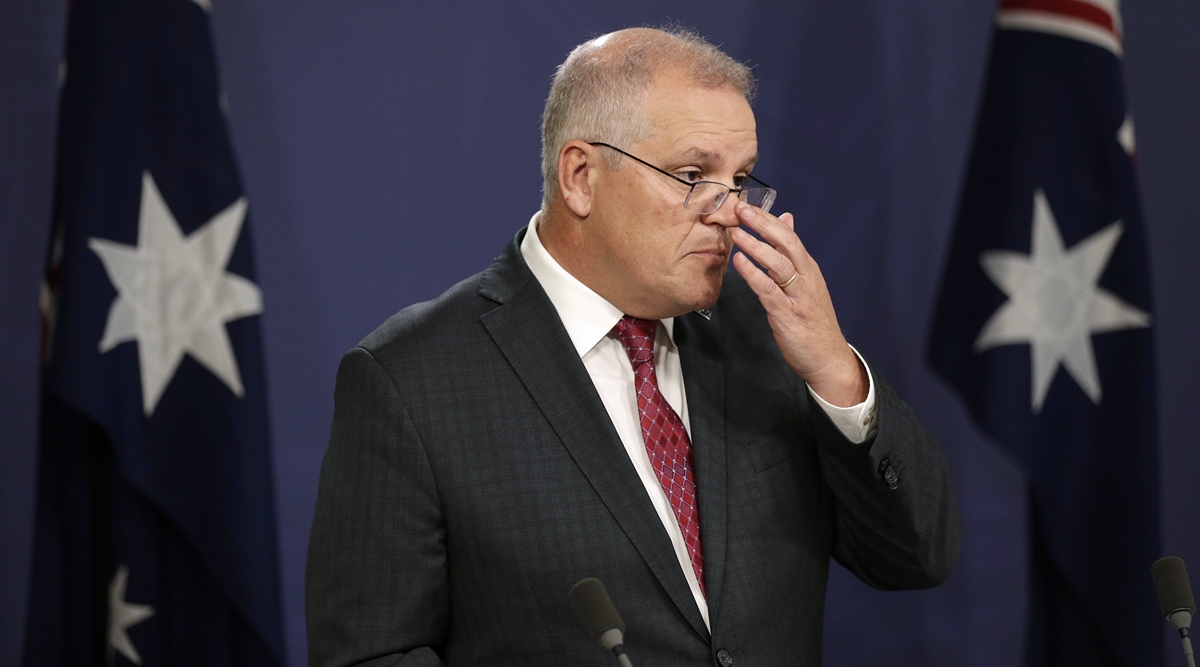

Australia PM Scott Morrison, has laid out an ambitious vision, saying that at least eight nuclear-propelled submarines using US or British technology will be built in Australia and enter the water starting in the late 2030s, replacing its squadron of six aging diesel-powered submarines.

When Australia made its trumpet-blast announcement that it would build nuclear-powered submarines with the help of the United States and Britain, the three allies said they would spend the next 18 months sorting out the details of a security collaboration that President Joe Biden celebrated as “historic.”

Now, a month into their timetable, the partners are quietly coming to grips with the proposal’s immense complexities. Even supporters say the hurdles are formidable. Skeptics say they could be insurmountable.

Australia’s prime minister, Scott Morrison, has laid out an ambitious vision, saying that at least eight nuclear-propelled submarines using US or British technology will be built in Australia and enter the water starting in the late 2030s, replacing its squadron of six aging diesel-powered submarines.

To pull off the plan, Australia must make major advances. It has a limited industrial base and built its last submarine more than 20 years ago. It produces a few graduates in nuclear engineering each year. Its spending on science research as a share of the economy has lagged behind the average for wealthy economies. Its past two plans to build submarines fell apart before any were made.

“It’s a dangerous pathway we’re treading down,” said Rex Patrick, an independent member of Australia’s Senate who served as a submariner in the Australian navy for a decade. “What’s at stake is national security.”

Each country has a vested interest in the partnership. For Australia, nuclear-powered submarines offer a powerful means to counter China’s growing naval reach and an escape hatch from a faltering agreement with a French firm to build diesel submarines. For the Biden administration, the plan demonstrates support for a beleaguered ally and shows that it means business in countering Chinese power. And for Britain, the plan could shore up its international standing and military industry after the upheaval of Brexit.

But the Rubik’s Cube of interlocking complications that pervades the initiative could slow delivery of the submarines — or, critics say, sunder the whole endeavor — leaving a dangerous gap in Australia’s defenses and calling into question the partnership’s ability to live up to its security promises.

“I don’t think this is a done deal in any way, shape or form,” said Marcus Hellyer, an expert on naval policy at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. “We sometimes use the term nation-building lightly, but this will be a whole-of-nation task.”

Failure or serious delays would ripple beyond Australia. The Biden administration has staked American credibility on building up Australia’s military as part of an “integrated deterrence” policy that will knit the United States closer to its allies in offsetting China.

The United States and Britain, for their part, face hurdles to expanding production of submarines and their high-precision parts for Australia, and to diverting expert labor to South Australia, where, Morrison has said, the boats will be assembled. Washington and London have heavy schedules to build submarines for their own navies, including hulking vessels to carry nuclear missiles.

“Success would be tremendous for Australia and the U.S., assuming open access to each other’s facilities and what it means in deterring China,” said Brent Sadler, a former U.S. Navy officer who is a senior fellow at the Heritage Foundation. “Failure would be doubly damaging — an alliance that cannot deliver, loss of undersea capacity by a trusted ally and a turn to isolationism on Australia’s part.”

Australia’s latest proposal contains many potential pitfalls.

It could turn to the United States to help build something like its Virginia-class attack submarine. (Such submarines are nuclear-powered, allowing them to travel faster and stay underwater much longer than diesel ones, but they do not carry nuclear missiles.)

But the two American shipyards that make nuclear submarines, as well as their suppliers, are straining to keep up with orders for the U.S. Navy. The shipyards complete about two Virginia class boats a year for the Navy and are ramping up to build Columbia-class submarines, 21,000-ton vessels that carry nuclear missiles as a roving deterrent — a priority for any administration.

Other experts have said Australia should choose Britain’s Astute class submarine, which is less expensive and uses a smaller crew than the big American boats. The head of Australia’s nuclear submarine task force, Vice Adm. Jonathan Mead, said this week that his team was considering mature, “in-production designs” from Britain, as well as the United States.

“That de-risks the program,” he said during a Senate committee hearing.

But Britain’s submarines have come relatively slowly off its production line, and often behind schedule. Britain’s submarine maker, BAE Systems, is also busy building Dreadnought submarines to carry the country’s nuclear deterrent.

“Spare capacity is very limited,” Trevor Taylor, a professorial research fellow in defense management at the Royal United Services Institute, a research institute, wrote in an email. “The U.K. cannot afford to impose delay on its Dreadnought program in order to divert effort to Australia.”

Adding to the complications, Britain has been phasing out the PWR2 reactor that powers the Astute, after officials agreed that the model would “not be acceptable going forward,” an audit report said in 2018. The Astute is not designed to fit the next-generation reactor, and that issue could make it difficult to restart building the submarine for Australia, Taylor and other experts said.

Britain’s successor to the Astute is still on the drawing board; the government said last month that it would spend three years on design work for it. A naval official in the British Ministry of Defense said that the planned new submarine could fit Australia’s timetable well. Several experts were less sure.

“Waiting for the next-generation U.K. or U.S. attack submarine would mean an extended capability gap” for Australia, Taylor wrote in an assessment.

Source: Read Full Article