Ever since the clashes between Israel and Palestine, social media has been ebbing with images, poems and videos of Edward Said and Mahmoud Darwish. But who are these individuals? What do they have to do with Palestine? The micro-narrative of social media conceals far more than it reveals.

Written by Shreya Banerjee

The shortest airline distance between Israel and Palestine is approximately 65 kilometres. A distance which is ideological, geo-poltical, religious and cultural. Many authors and poets over the ages have used their craft, poetry and academic scholarship to fill this gap- with the hope that someday ‘violets shall grow from the soldier’s helmet’ (The Sleeping Garden, 1977, Darwish).

Ever since the clashes between Israel and Palestine, social media has been ebbing with images, poems and videos of Edward Said and Mahmoud Darwish. But who are these individuals? What do they have to do with Palestine?

The micro-narrative of social media conceals far more than it reveals. What these fragments of information fail to identify are the social, political, historical and cultural spaces these individuals inhabited- both in their own ways, which cannot be fitted into one another. What can be examined, however, is what these spaces mean, how they are read and how they translate into meaning. At a time when hostilities were raging only a while back, it is imperative that we pause and consider who these men are and what they stand for years after their passing.

Mahmoud Darwish

In 1948, the village of al-Birwah in the district of Galilee, was demolished along with 416 other Palestinian villages. Among its inhabitants was six-year-old Mahmoud Darwish who was forced to leave his homeland and escape to Lebanon. A year later he returned to Palestine ‘illegally’ and settled in the nearby village of Dayr-al-Asad. However, they were no longer counted as Palestinians. Darwish was legally classified as a ‘present-absent-alien’ and culturally appropriated as an ‘internal refugee’.

The village of Birwe was obliterated from geo-politics but it lived in young Darwish’s memory as the vestige of a lost Paradise.

The loss of the homeland was followed by a lifelong search for something that could come closest to endurance. Darwish went on to create a homeland for him and his people through words, poetry, and lyrical prose. Darwish’s works aim to answer the ricocheting question ‘who am i?’, a question which tormented him his entire life. In Darwish, “the personal and the public are always in an uneasy relationship” wrote Said in his essay On Mahmoud Darwish.

As German philosopher Martin Heidegger once said, ‘Language is the house of being’, Darwish created his ‘house of being’ through words and verse. His entire oeuvre is, therefore, a site of resistance. At best, his works are a flux, a dialectic, that is able to contrast presence and absence in a way that reverberates the voices of the dispossessed people of Palestine.

Darwish’s text In the Presence of Absence is a curious work of poetry in prose. Owing to a history of heart disease, the Palestinian National poet wrote the book at a time in his life when he believed that the work could be his last one. In light of this, Sinan Antoon, the translator of the piece in English, states in the preface that Darwish wanted to create a space where “presence absence, prose poetry and many other opposites converse and converge.” It is a work which ‘defies categorisation’. It is a self-elegy, an attempt to immortalise the life of several nameless ‘present-absentee’ Palestinians in a literary genre which doesn’t fit into the limits of any classification. Almost like a child wandering aimlessly, the prose walks us from “a side street, a post office, a bread seller, a laundry, a tobacco shop, a tiny corner, and a smell that remembers” to the lines “the poetry of exile is not what exile says to you, but what you say to it, one rival to another. Exile too is hospitable to indifference and harmony.’

ALSO READ |Painting the Spanish Flu: How iconic art and literature depicted the ailing, the dead

Interestingly, the cover of the book mimics a tombstone. If the name of the author and the title is read in one breath it reads “Mahmoud Darwish in the Presence of Absence” This profoundly meditative piece is emblematic of the exile whose weight Darwish rested in his words. Except here, the tomb does not signify cessation, it only immortalises the poet and his people’s lives in words and verse.

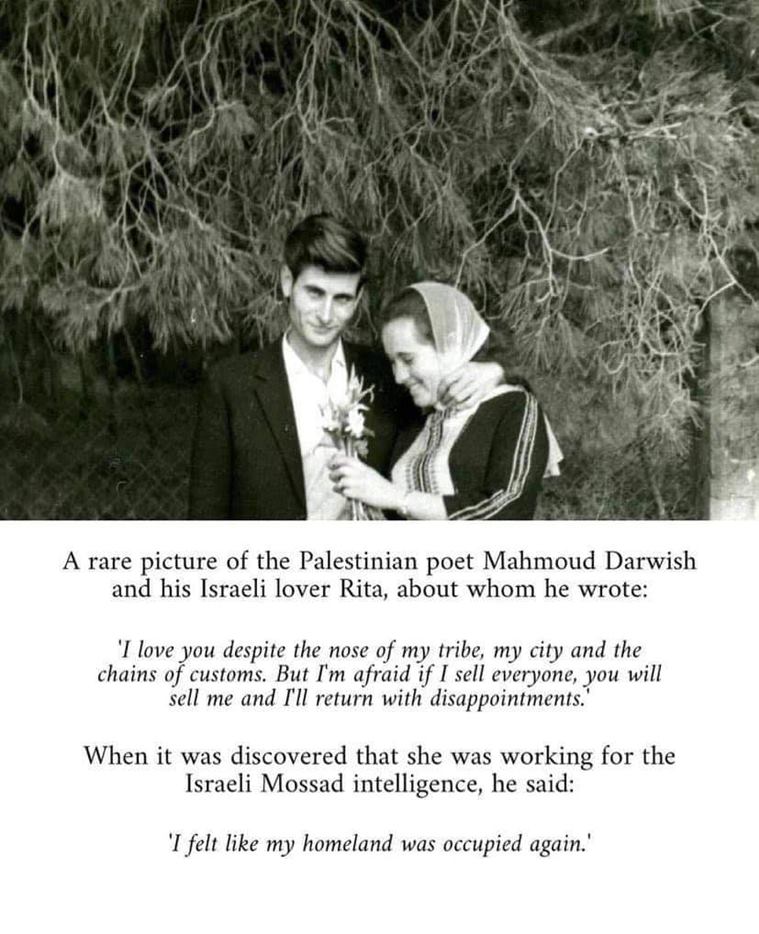

A widely circulated post on social media claims ‘Rita’ to be Darwish’s beloved who became a spy. There are records which testify to the former but not the latter. ‘Rita’ is the nom-de-plume for Tamar Ben-Ami. Darwish fell in love with Jewish-Israeli Tamar when he was 22. The Palestinian national poet memorialised Rita’s short-lived presence in his life through poems like Rita and the Rifle, Rita’s Winter and The Sleeping Garden. Theirs was a romance which was transgressive: one that could appear to be incongruous with the poet’s politics. However, In his poems addressed to Rita, we see an attempt to humanise the enemy. The name ‘Rita’ recurred in many of his later poems, long after Rita had severed ties and joined the Israeli Military. The imagery of the ‘rifle’ in Rita and the Rifle alludes to Rita’s enrollment into the military.

There’s a rifle between Rita and me

Whoever knows Rita bows and prays to a god in those honey eyes …

O Rita nothing could turn your eyes away from mine except

A snooze

Some honey clouds

And this rifle.

Inspired by this free-spirited romance, filmmaker Ibtisam Mara’ana Menuhin made the 2014 documentary Write down, I am an Arab. The name of the film was borrowed from one of Darwish’s most defiant poems. In 1964 this poem landed him in prison and turned him into an icon of the Arab world. During this time frame, he met and fell in love with Tamar Ben-Ami. The film reveals their handwritten love letters in Hebrew, which Tamar kept secret for decades. Write Down, I Am an Arab draws a deeply personal and political picture of the poet . Through his poetry, secret love letters, and exclusive archival materials, Menuhin unearths the story behind the man who became the mouthpiece of the Palestinian people.

Edward Said

In the Introduction to If I Were, Fady Joudah writes that “The two protagonists (Darwish and Said) converge and part over exile as “two in one / like a sparrow’s wings,” in diction that seems like talk over coffee or dinner.”

Fellow Palestinian exiles, Said and Darwish had been friends for decades. Ideologically, both had their moments of close concord but also a few vacillations. In 1994 Said published an essay titled On Mahmoud Darwish, while on the other hand in 2004 Darwish wrote an elegy titled Tibaaq in memory of his friend and compatriot Said. These two works foregrounded and memorialized their friendship, politics and resistance.

Only a week back, this image of Said throwing stones at Israeli authorities surfaced on Twitter. The image traces back to July 3, 2002. This image captured by a photographer from Agence France-Presse had angered many Israelis. In May 2000, when Israeli troops withdrew from southern Lebanon after 18 years of occupation, it was ‘customary’ for Arab tourists to throw stones over the wire fence, which was hastily erected after the Israeli withdrawal.

On being asked about this event, Said told reporters that it was ‘a symbolic gesture of joy’, and was aimed at nothing or nobody.

The Arab Press was critical of this incident. After the 2000 incident, Beirut Daily Star stated that they were disappointed that a scholar “who has labored . . . to dispel stereotypes about Arabs being ‘violent’” reversed course, and let himself “be swayed by a crowd into picking up a stone and lofting it across the international border.” The student newspaper of Columbia University, where he taught, the Columbia Daily Spectator, commented that Said’s actions were “alien to this or any other institution of higher learning.”

Said released an official statement two days after the incident, in 2000, stating that “one stone tossed into an empty place scarcely warrants a second thought.” He warranted that in his works he had been writing and critiquing tirelessly to ease tensions between Palestinians and Israelis.

“…As if that could ever outweigh the work I have done over 35 years on behalf of justice and peace,” Said wrote, “or that it could even be compared with the enormous ravages and suffering caused by decades of military occupation and dispossession.”

Edward Said was a man of multitudes and interesting paradoxes. He was heavily inspired by French philosopher Michel Foucault, italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci, French anthropologist Claude Levi-strauss and German philosopher Theodor Adorno. Many cities, memorabilia, interviews and enduring friendships enable us to understand this man who has produced works in genres as vast as memoir, literary theory and criticism; analyses of photography, music, film, dance; as well as political dissertations.

In an interview with Salman Rushdie, Said distills the Palestinian experience in the words ‘we weren’t exploited, we were excluded.’.

A Christian and Palestinian, Said grew up in Cairo and Jerusalem. Belonging to a family of Protestant Christians, Said defined themselves as ‘a minority inside a minority’, “My family and I were members of a tiny Protestant group within a much larger Greek Orthodox Christian minority, within the larger Sunni Islam majority,” he said in the interview with Salman Rushdie.

In his memoir Out of Place, Said writes that ‘it took me about fifty years to become accustomed to, or more exactly, feel less uncomfortable with, “Edward” ”. A name he calls ‘foolishly English’, ‘yoked forcibly to the unmistakably Arabic family name Said’.

Said’s father fought in WW1 for the US as a result of which Said received an American citizenship. In his memoir, Said fumbles with these scraps of his identity. His ‘I’ or the notion of the self dwindles in the wind. For Said, reconciling with his identity as an American Citizen was a kind of dissonance. Like Darwish, all his life he had to grapple with these ‘disconcerting orbits’ of his identity. Eternally uprooted, the last line of his memoir reads: “With so many dissonances in my life I have learned actually to prefer being not quite right and out of place.”

In perspective of the political landscape of pre-1967 Israel, Said was against political leader and Chairman of Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Yasser Arafat’s breach of the right of return law- which denied Palestinian refugees to return to their homes and assets. For many years he was an ardent supporter of Arafat. What caused Said to break away from Arafat’s politics was the 1993 Oslo accords between Israel and the P.L.O. Said believed that the agreement gave the Palestinians too little territory and too little control. It caused a rift between him and Arafat.

In the years that followed the Oslo accord, he argued that separate Palestinian and Jewish states would be unrealisable. While he recognised that both sides were against it, he advocated a single binational state as the most suitable solution.

“I see no other way than to begin now to speak about sharing the land that has thrust us together, and sharing it in a truly democratic way, with equal rights for each citizen,” he wrote in a 1999 essay in The New York Times.

In 1989, Said firmly condemned Iranian political and religious leader Ayatollah Khomeini’s ‘fatwa’ ordering Muslims to assassinate Rushdie. He even contended for Rushdie’s literary freedom in his essay “The Public Role of Writers and Intellectuals”

In one of his most illuminating works, “Orientalism,” Said lays down his theory of orientalism in how the West conjured the East. It lays bare the problematic preconception that the east was inherently corrupt, contemptuous, backward and full of diseases. “The relationship between Occident and Orient is a relationship of power, of domination of varying degrees of a complex hegemony,” wrote Said in Orientalism.” The cultural currency of the west enabled them to politically dominate the east. Said ruminated upon the power dynamics that existed between the coloniser and the colonised. Said traced the dynamic between imperialism and culture throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. He was the first to introduce the ‘imperialism vs culture’ discourse and political dynamic as a part of American scholarship.

Said and Darwish continue to be two of the most compelling intellectuals of the Arab world. While Said addressed everything from Palestine to Pavarotti, Darwish gave us a language to articulate the disjointedness of exile.

Further readings

Darwish, M (2011. In the Presence of Absence. ). Translated by Sinan Antoon . Archipelago Books

Said, E (2000). Out of Place: A Memoir. Vintage Books.

Darwish, M (2008).A River Dies of Thirst. Translated by Catherine Cobham . Saqi Books.

Said, E (2001) Interviews with Edward W. Said. Edited by Gauri Vishwanathan. Vintage Books.

Said, E (2001) Orientalism. Penguin Books

Source: Read Full Article