How long this welfare approach is sustainable without enlarging the size of GDP pie is an open question

Get email alerts for your favourite author. Sign up here

Last week, the Narendra Modi government completed seven years at the Centre. It is facing headwinds on the politico-economic front due to carnage unleashed by second wave of Covid-19 and below expectation performance in state assembly elections. Yet, it is time to reflect and look back at its performance on basic economic parameters over the last seven years. It may also be interesting to compare and see how it fared vis-à-vis the first seven years of UPA government (2004-05 to 2010-11) under Manmohan Singh. Recall the famous quip of the former PM when he said, “History will be kinder to me than the contemporary media” while giving a press conference in early 2014.

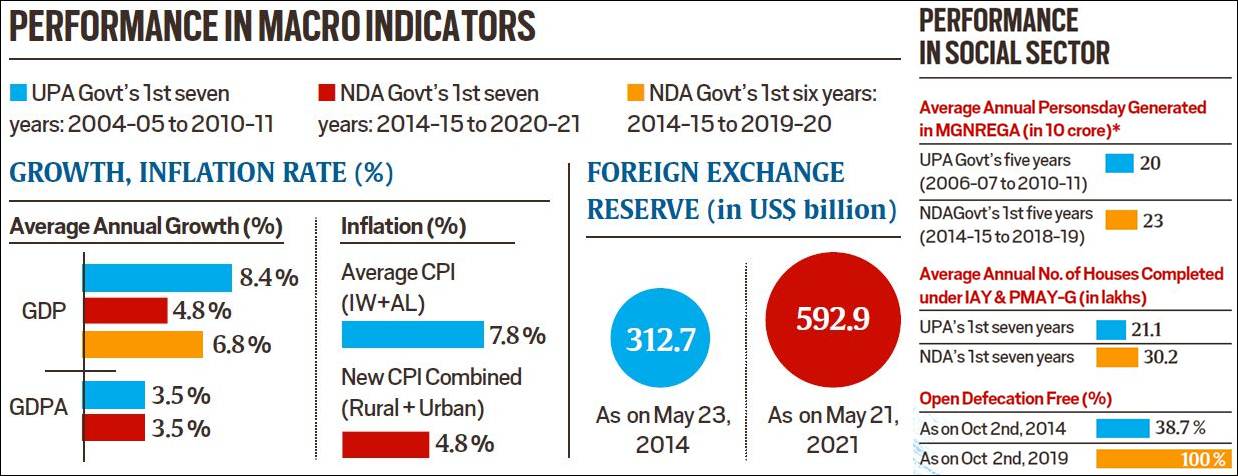

One of the key economic parameters is GDP growth. It is not the most perfect one, as it does not capture specifically the impact on the poor, or on inequality, but higher GDP growth is considered central to economic performance as it enlarges the size of the economic pie. Infographics below show that the average annual rate of growth of GDP under the Modi government so far has been just 4.8 per cent compared to 8.4 per cent during the first seven years of the Manmohan Singh government. Even if one excludes the year 2020-21 (FY21), due to massive contraction caused by Covid-19, still the average of six years of Modi government stands at 6.8 per cent, way below Manmohan Singh’s 8.4 percent. If this continues as business as usual, the dream of a $5 trillion economy by 2024-25 is not likely to be achieved.

However, the Modi government scores much better on the inflation front with CPI (rural and urban combined) rising at 4.8 per cent per annum. It is well within the tolerance limits of RBI’s targeted inflation band and also much lower than 7.8 per cent during the first seven years of the Manmohan Singh government. Also, at macro level, foreign exchange reserves provide resilience to the economy against any external shocks. On this score too, the Modi government fares quite well with forex reserves rising from $313 billion on May 23, 2014 to $593 billion on May 21, 2021.

My main interest, however, is food and agriculture, as it engages the largest share of the workforce in the economy and matters most to poorer segments. On the agri-front, both governments recorded an annual average growth of 3.5 per cent during their respective first seven years. However, on the food and fertiliser subsidy front, the Modi government broke all records in the pandemic year of FY21, by spending Rs 6.52 lakh crore (38.5 per cent of all revenue of the Union government, as per CGA) and accumulating grain stocks exceeding 100 million tonnes in May end, 2021. This actually speaks of massive inefficiency in India’s grain management system, and PM Modi shied away from reforming this sector. One area in which the Modi government performed very poorly is agri-exports. In 2013-14, the last year of the UPA government, agri-exports had crossed $43 billion while during all the seven years of the Modi government agri-exports remained below this mark of $43 billion. Sluggish agri-exports with rising output put downward pressure on food prices. It helped contain CPI inflation, but subdued farmers’ incomes. Given this, the dream of doubling farmers’ real incomes by 2022-23 may remain just a pipe dream.

Infrastructure development is critical for the long-term growth of the economy. The Modi government has done better in power generation by increasing it from 720 billion units per annum during Manmohan Singh’s first seven years to 1,280 billion units per annum. Similarly, road construction too has been at least 30 per cent faster under the Modi government.

Let us turn to the social sector, which is critical for those at the bottom of the economic pyramid. We don’t have any reliable data from the government on India’s headcount poverty ratio after 2011. The NSSO consumption survey of later years has not been released. But based on an international definition of extreme poverty (2011 PPP of $ 1.9 per capita per day), the World Bank estimated India’s extreme poverty in 2015 to be about 13.4 per cent, down from 21.6 per cent in FY 2011-12. Even the incidence of multidimensional poverty hovered around 28 per cent in 2015-16.

We have taken three key indicators to assess performance on this front: One, average annual person days generated under MGNREGA in the first five years since this programme started under the UPA in 2006-07 to 2010-11, which was 200 crore, and under Modi government it improved to 230 crore; two, average annual number of houses completed under the Indira Awaas Yojana and PM Awaas Yojana-Gramin, which improved from 21 lakhs to 30 lakhs per annum; and three, open defecation free (ODF) which was only 38.7 per cent on October 2, 2014 and shot up to 100 per cent by October 2, 2019, as per government records. This is indeed commendable. Prioritising toilets before temples, the Modi government achieved an ODF status which was not done in 67 years since independence.

Overall, it is clear that the Modi government has not performed well on the GDP front. But its record on the agri-GDP front compares well with the seven years of UPA, and its performance in infrastructure and welfare programmes, from power generation to roads, MGNREGA jobs to houses and toilets for the poor, is surely better. One may argue that these numbers need to be normalised with, say, people below poverty line or some other deflator, but still I would say that the Modi government has turned out to be more welfare-oriented than reformist in revving up GDP growth. How long this welfare approach is sustainable without enlarging the size of GDP pie is an open question.

One can only hope that once Covid-19 is contained, the government can focus on growth policies and India will bounce back. Surprisingly, even amidst this gloom, the Sensex has been roaring, ignoring even the RBI’s warning of a possible bubble burst. In the meantime, policymakers need to boost demand, support MSME, and invest in health and agri-infrastructure in rural areas for the remaining period of the Modi government.

This column first appeared in the print edition on June 7, 2021, under the title “A seven-year report card”. The writer is Infosys Chair professor for Agriculture at ICRIER

Source: Read Full Article