In Sherni, conservation is not about heroics, but the fine balance between wildlife and people

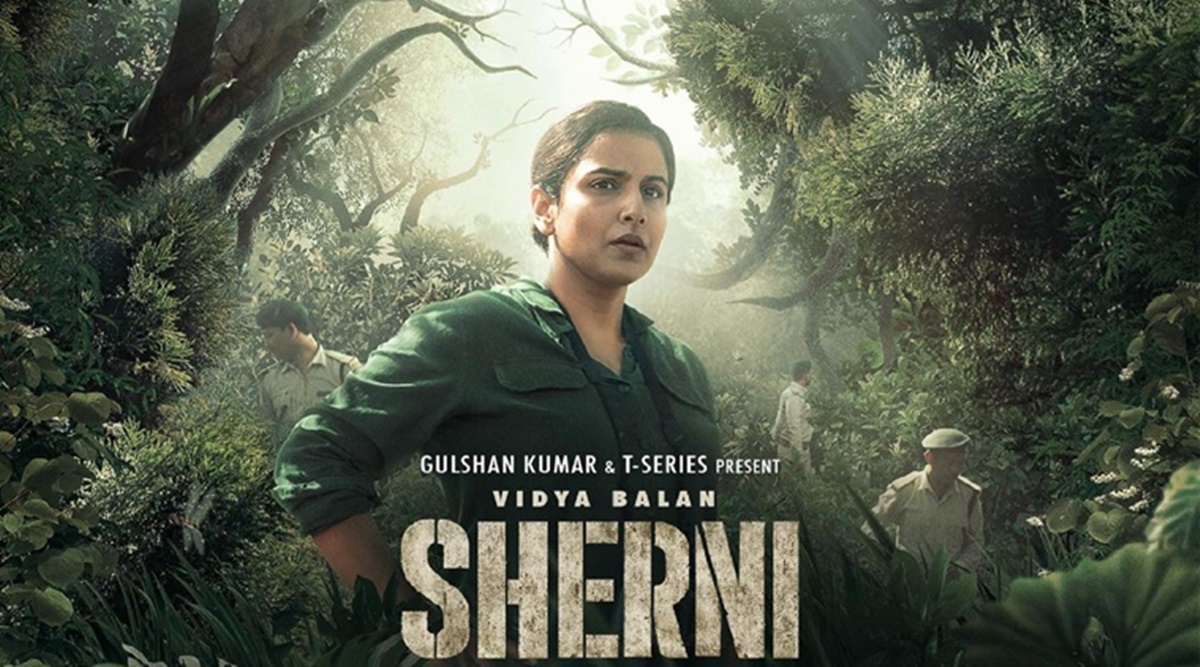

Amit Masurkar’s Sherni is an unusual film for many reasons — it has a laconic, soft-spoken female bureaucrat as a protagonist, the film is set in the forests of Balaghat, Madhya Pradesh, and explores issues of wildlife conservation and environmentalism. Inspired by the events surrounding the 2018 killing of Avni, a man-eating tigress, in Maharashtra, Sherni focuses on the struggles of forest officer Vidya Vincent (played by Vidya Balan) trying to safely capture a big cat before trophy hunters or aggrieved locals get to her.

In less than five minutes of runtime, Sherni shows what a day in the life of an Indian Forest Service officer posted in the field actually looks like. In the opening scene, a team of forest guards sets up a camera trap to observe the tigers of the area. Vidya reprimands them about a dry watering hole in the forest. A staff member sheepishly informs her that the maintenance of the watering hole is up to a contractor who happens to be the nephew of a local politician. The scene shifts to the forest department office, with its rickety chairs, a large tiger portrait in a senior officer’s chamber, mounds of dusty files, and disinterested clerks plodding through desk work. Masurkar’s visuals of the backwaters of forest bureaucracy have an unsettling intimacy.

As the daughter of a forest officer, I noted with satisfaction the details that the film got right, from quaint colonial bungalows, the heat and dust of sarkaari offices, the vast breadth of staff who make up the forest department—trackers, guards, rangers, clerks and IFS officers—to the sounds of the forest at dusk. The forest department is also one of the more eccentric workplace cultures, where the presence of certain “characters” is taken for granted — be it the khansaama who can regale you with tales about the forest as he serves you dinner, tipsy uncles who launch into old Hindi songs at official parties after a few drinks, or the trackers and field experts who affectionately discuss the latest exploits of the local tiger, as if it were a mischievous but beloved pet and not a 300 kg wild beast.

There is an India that lives in forest villages, populated by adivasis and forest-dependent communities. It is caught in the complicated matrices and competing interests of conservation, local politics, development and, in many cases, Maoist militancy. It is a precarious and occasionally uneasy coexistence with wildlife, but remains a way of life with ancient roots. In this twilight zone of contemporary Indian imagination, hardly ever represented in Bollywood, a few men and women try to do their thankless jobs with honesty and grit.

Vidya starts off as a lonely, demotivated woman struggling in a professional environment, where she is seen as an anomaly, a “lady officer” who is met with either hostility or condescension. She lives alone in her rambling home, distant and separated from a husband who does not understand the struggles of her job, with only a kitten for company. There is a quiet desperation, unquestionably gendered, that fuels Vidya’s dogged determination to save local villagers, the tigress and her cubs from preventable deaths. The film does not reward her with a heroic end and yet this is, perhaps, the only representation of a committed woman public servant in Hindi cinema, a welcome addition to a longer tradition of socially-conscious films like Ardh Satya, Swades, Shanghai and Article 15 (and arguably superior to some examples stated here).

The film depicts the larger necropolitics of what makes the lives of villagers and wildlife so disposable to the powers that be; how cruelly the system fails local communities. Villagers are forced to take the risk of venturing into a forest stalked by a tiger because Vidya’s predecessor cleared the village grazing grounds to plant revenue-generating trees. The model of conservation that Vidya upholds includes looking beyond the confines of her department. Her dedicated motley team includes experts (in the form of Noorani, the local professor turned conservationist played by Vijay Raaz), daily-wage trackers, forest guards – including a number of “lady guards” – and local women with whom she forms partnerships. The film, thus, does not present conservation as simply “catching hunters” or “punishing the man-eating tiger”, but as a complex, multi-faceted project that seeks to preserve a delicate but critical balance between humans and nature.

The writer is a PhD scholar at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland

Source: Read Full Article