A true-blue liberal and a staunch idealist, the filmmaker was relentless in his pursuit of telling a story in the most authentic fashion possible

For a filmmaker whose creations are deeply rooted in realism and explore heavy societal themes often from a cynical perspective, Mrinal Sen was obsessed with Charlie Chaplin and his antics as the lovable tramp.

“One of the first films I saw was Chaplin’s The Kid when I was eight or nine years old… I loved it… I became wise after watching his films,” Sen expressed gleefully in one of his last interviews with DD National.

Throughout his career spanning over five decades, Sen exhibited the same affinity for the poor and downtrodden as Chaplin. Only he used the device of a gritty drama instead of a laugh out loud comedy to actualise his vision.

Also Read | Get ‘First Day First Show’, our weekly newsletter from the world of cinema, in your inbox. You can subscribe for free here

And it all began when he landed in Kolkata from Faridpur (now in Bangladesh), in the early 1940s, to study Physics at Calcutta University.

Soon, he became intertwined with left-wing student politics, and after graduation, took up various odd jobs until he made his first movie, Raat Bhore (The Dawn) in 1955, which was a disaster. While Satyajit Ray’s first cinematic offering Pather Panchali (Song of the Road) released to worldwide acclaim the same year, Sen was still reeling from the failure of his inaugural magnum opus, indulging in deep self-reflection.

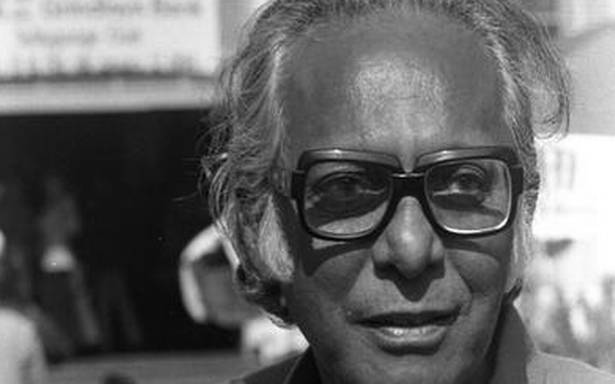

In many of his films, Sen exhibited the same affinity for the poor and downtrodden as Charlie Chaplin | Photo Credit: PTI

Subsequently, his second film Neel Akasher Neechey (Under The Blue Sky) in 1958 was the first film in independent India to get banned. The story of a Chinese hawker, who, while navigating the streets of Kolkata, forges an unlikely friendship with a Bengali housewife, failed to impress the Jawaharlal Nehru govt for its critical take on Indian society. The ban lasted three months before the film could secure a release.

Unrattled, Sen soldiered on, and in 1960, his third film Baaishey Shravana (The Wedding Day), set in the time of the Bengal Famine of 1942, finally had the desired effect. Not only was it accepted by mainstream audiences, but also became his first film to reach an international audience after it was selected for the London Film Festival.

Following that, Sen’s collaboration with the legendary actor Utpal Dutta in Bhuvan Shome (1969) earned both of them a national award. Self-taught on the finer nuances of film aesthetics, Sen was hell-bent on implementing the Eisnetian technique of ‘montage’ creation.

With Bhuvan Shome, he accomplished the same, running wild with its narrative structure — leading the efforts to establish the Indian ‘New Wave’ film movement as a driving force in the world of cinema in the post-war years. It also featured the most unlikely debutant, albeit, only his voice made it into the film — that of Amitabh Bachchan’s — the first time he got paid for working on a movie.

A still from Mrinal Sen’s ‘Bhuvan Shome’

Then began the 1970s, and with it came Sen’s finest creation: The Calcutta Trilogy — a collection of three feature films — Interview(1971), Calcutta 71 (1972) and Padatik (1973).

Calcutta 71 garnered the most attention. An anthology film where contrasting stories overlap effortlessly while making no efforts to hide their radical overtones; this Mrinal Sen offering transported viewers back in time to different eras witnessed in Kolkata. The film released when West Bengal was in the grips of Naxal violence, and the master storyteller Sen was able to capture on celluloid, the burning anxieties of the time with much elan.

Interview and Padatik were similar in their exploration of radical themes, showcasing cinematically the excesses committed by authority figures, bringing to the forefront the plight of the ambitious Bengali youth.

A still from Mrinal Sen’s ‘Padatik’

However in the 80s, Sen ditched his experimental style for a rather conventional, understated approach to portray remarkable tales of social and cultural significance.

In his 1982 classic Kharij, he stitched together a peculiar chain of events that followed the mysterious death of a servant boy in a middle-class household. The production holds ground to this day, with its simple-yet-stark portrayal of India’s rigid class structure and the inequalities which stem from it.

Separately, the city of Kolkata is a recurring motif in most of Sen’s films. Most of his protagonists embody the spirit of his beloved city, and in turn, the metropolis seems to be a party to the pangs of their day-to-day existence.

Despite this, his body of work is not just restricted to Kolkata and its Bangla-speaking inhabitants. He has directed various Hindi movies featuring prominent actors of the time like Naseeruddin Shah (Khandar, Genesis) and Shabana Azmi (Ek Din Achanak). He has also been credited with directing a Telugu film by the name of Ooka Oori Katha, which Satyajit Ray hailed as a masterpiece.

Mrinal Sen receives the Shiromani Vikas Award from Mother Teresa, in Calcutta on November 28, 1992 | Photo Credit: PTI

On the occasion of his 98th birth anniversary, not much can be said about the late stalwart that hasn’t already been put into words.

A true-blue liberal and a staunch idealist, Sen was relentless in his pursuit of telling a story in the most authentic fashion possible, refusing to bend down to the dictates of any external forces that came between him and his creations. Something unheard of in the present-day Bollywood landscape, where selling out to the highest bidder is more of a norm than the exception.

Source: Read Full Article